The inevitable consequence of Sony’s massive security screwup is that I’ve drowning in phish: fraudulent emails purporting to be some vendor or other, saying that my account has been deactivated and asking me to “confirm” credit card numbers and other personal data. The personal information of nearly 100 million Sony users was accessed (75 million announced last week, another 23 million this week). Given all the fraudulent credit card activity that must be generating, it’s a great time to go out collecting even more credit card numbers by sending fake email telling people their accounts have been suspended for suspicious activity.

So it’s time for a really brief review of online safety, at least with respect to phishy email:

- Never trust any email communication asking for your credit card number. If a vendor does business with you, they know your credit card number already. If they need to “confirm” it, they can find some other way to contact you.

- Never click on a link in an email message; you don’t know where that’s taking you. If you receive email from Amazon asking you for information, and you think it might be legitimate, type the URL into the browser yourself. Even if it’s long.

- Since phishes tell you your credit card account has been put on hold, you might as well check. Again, don’t click on the link in the email; type it in yourself. If your account has actually been suspended, the vendor will make it easy for you to find out.

- Do check your vendor’s policy on their use of email. Amazon’s policy lists information they will not ask for (including credit card numbers), and states that they won’t ask you to verify your account information by clicking on a link in an email, etc. Unfortunately, finding their policy page could be easier than it is. There are other sites like phishtank that purport to maintain a global database of phishing sites. Don’t hesitate to use them.

- To the extent that the vendor allows you to report phishing attempts, do so. I have not always found vendors to be proactive, and to be honest, it’s so easy to set up a phishing site (you can find plenty of kits for doing so online), that it’s really like playing Whac-A-Mole: shut one down and two more pop up. But hey, it makes you feel like you’re accomplishing something. Amazon asks you to forward suspicious email to stop-spoofing@amazon.com, and responds with an email message giving advice similar to what I’ve outlined above.

The Amazon phish I received this morning was extremely simple and easy to detect. There were two giveaways:

First, if you save the HTML that came with the email, and look at it with a real text editor like Emacs or Vim, you’ll notice that the URL for the Amazon logo is http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/amazon-logo.jpg. The sender is picking the logo up from the Chicago Sun-Times, not from Amazon’s corporate servers. To be clear, there’s no reason a phishing site can’t pick up design elements from the sites they’re impersonating. This attack was particularly clueless.

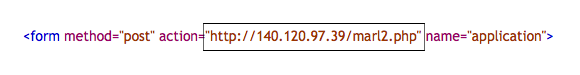

Second, the real giveaway is the included form. The URL for form submission is http://140.120.97.39/marl2.php. No hint of Amazon there. If you should click on that “submit” button, where is it going? I don’t know, and neither do you. A traceroute to that address showed it disappearing somewhere in Taiwan before losing track.

That gives you an idea how the phish works: victims fill in a form and click a “submit” button, and it’s all over. If you look, you can find sites selling stolen credit card numbers. That’s where these will end up.

This phish was particularly clumsy. I’ve seen sites that included non-printing characters in the URL so that it looked correct when it was in the browser’s URL bar. It might even look correct when you’re inspecting the HTML, if you use an editor that’s easily tricked. (That’s why I recommend Emacs or Vim.) I’ve seen phishes that substituted 0 for O, or used other character substitutions, to create URLs that look legitimate but aren’t.

However, though you may have fun looking at the actual phish and figuring out what’s wrong with it, don’t go the other way: Never decide that a suspicious message looks legitimate and act on it. It isn’t. If your vendor doesn’t have a statement about what they will and won’t do when contacting you via email, assume they follow Amazon’s policy. And if they don’t — if they really do ask you for your credit card number via an email message — let them suspend your account. You shouldn’t be doing business with them anyway.

In a phone conversation about a year ago, security researcher Jeff Jonas told me that the future of phishing was very scary: phishing mails would come with enough personal information (knowledge of products you’ve bought, people you know) that it would be almost impossible for a victim to detect fraud. The extent of the Sony data breach is so massive that we may be about to fall off that cliff. I don’t know if we’re headed there yet, but it’s clear: Sony has handed Internet criminals a tremendous gift. They’re going to use it. There’s going to be a lot of identity theft and other forms of fraud, and there will be phishers seeking to take further advantage of that situation.

Related: