Critics of the gamification movement — mostly composed of

academics and traditional game developers — have written a range

of impassioned blog posts and gone on rants at legacy game industry

events.

I think you deserve to hear a good, substantive critique of

gamification. That’s why I ensured that opposing viewpoints were heard

— unobstructed — at GSummit in San Francisco, and why they will once

again be front and center at Gamification

Summit NYC in September. That’s also why I’ve decided to write an

earnest critique of gamification here. I’ll present the arguments that

I think are meaningful and important, and you can decide if you agree.

Constructive dialogue welcome.

Let’s get a few common arguments out of the way up front.

First, that the word “gamification” itself is inappropriate

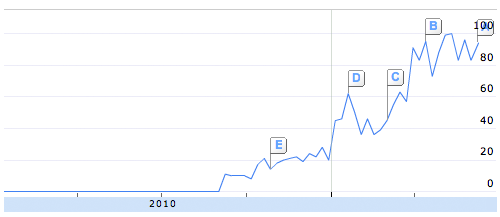

or bad. The term has entered the popular lexicon, rising from

nearly zero hits on Google 18 months ago, to around 900,000 today (and

climbing). As with most powerful tech neologisms, it’s probably not

going anywhere, and no small part of its success is that it genuinely

is the first viable term to encapsulate the concept of using game

concepts outside of games. It has also hit the zeitgeist at the

appropriate time.

This chart shows interest in gamification from January 2010 to June 2011. (Click for additional information from Google Insights for Search.)

Semantically, many game developers also argue that gamification

demeans “games,” quickly forgetting the fluidity of market

categorization. At one time or another in the past decade, casinos,

amusement parks, virtual worlds, casual, mobile and social games have

all been questioned as belonging to the games industry. The simplest

and best argument I’ve heard for this was made by Nick

Fortugno, co-founder of Playmatics and designer of hit casual game

Diner Dash: “Gamification is to games as jingles are to music.” In

summary: they are different but related disciplines that leverage

similar techniques and technologies.

The argument made most often, and least compellingly by detractors

is in essence that bad gamification is

bad. Sometimes this takes on a solipsistic angle (“I don’t

like Farmville, so it’s bad”), and is almost always condescending to

the hundreds of millions of people who engage actively with these

gamified experiences. These critics seem to be arguing that if marketers,

enterprise architects, HR professionals or product designers get hold

of game mechanics, they are certain to demean the art form (worst-case)

or build something pointless (best-case).

Obviously, these arguments are circular. Any bad design is

inherently bad — and terrible games suck just as much as bad

film (though with generally far less camp value). Every game designer

has some successes, and some failures — the same is true of most

marketers, product designers, book publishers and entrepreneurs.

Businesses seeking gamification almost always want to hire skilled,

experienced game design talent — and I believe the market will demand more

than 10,000 trained designers in the coming decade for industry,

government and non-profit gamified design. Game designers can readily

be part of the solution if they choose.

Now let’s talk about the important stuff. In my opinion, there are

three credible concerns about gamification that require further

scientific inquiry and should be explored.

Replacement and over-justification

In my undergraduate work, I studied the psychology of gifted

children. Prominently featured in the literature was a concept called

over-justification. In over-justification, children who are intrinsically motivated toward a specific activity — playing piano, say — can have that intrinsic desire extinguished by the

introduction and subsequent removal of extrinsic

rewards, such as trophies or cash. So even if your child always loved

to play the piano, winning and then losing at conservatory

competitions may stop your child’s piano playing for good. In a sense,

their intrinsic desire to play was extinguished by a failure to

maintain continuous rewards from the outside reward system.

Though the behavior extinguishment loop is well documented, what to

do about it is another issue entirely. Taken to its logical extreme,

this phenomenon argues for the complete elimination of external reward

and competition. It would seem that in order to preserve intrinsic

motivation, parents should never encourage their children to compete

at something they naturally care about, lest that spark be eliminated.

Obviously, that’s facile. Competition is part of our society and

always has been. Moreover, extrinsic rewards are essential in

capitalism (our salaries, bonuses, dividends, titles, etc. are all

forms of extrinsic rewards). We can’t remove them without dismantling

our economy — and why would we? If you are successful at

pursuing your intrinsic dreams, over-justification isn’t a problem;

successful piano players generally don’t suffer a lack of motivation.

The best thing parents (and designers) can do with the knowledge of

over-justification is to teach children how to combat negative

reinforcement so they have the emotional strength to overcome

adversity.

But if intrinsic motivations are ignored in gamified design, the

resulting product is likely to be shallow, with engagement loops to

match. This means that aligning internal and external benefits makes

gamified apps that much better. It also means that gamified apps that

are designed from scratch have an inherent advantage over those where

gamification is added later.

True cost of ownership

As a relatively new field, total cost of ownership is a misunderstood concept in gamification. In most kinds of marketing programs — even those with long lifespans — there are

finite ends to promotions based on either time or budget. By contrast,

gamified systems are more like multiplayer online games and loyalty

programs. Once users become accustomed to the interactions we design,

they expect the rewards to continue and evolve with both their mastery

and tastes.

Even a few years ago, gamifying something meant building the whole

tech infrastructure from scratch — a costly exercise that is no

longer necessary due to the work of companies like Badgeville and BunchBall. Today, the biggest up-front cost of gamifying something is in the design and testing —

which is a boon to the market. However, there are critical ongoing

costs that are not always obvious, including compliance/legal costs

and economic balancing (if you’re running a virtual economy),

community management and policing, and continuous creative (avatars,

challenges, etc). If you use agile techniques to roll out

gamification, you can optimize the chances of success and phase

investment accordingly. Regardless, if you do your job right,

gamification is a multi-year project, and you must budget and prepare

accordingly.

Addiction/compulsion

Although we have many successful implementations, the long-term

effect of gamification on users is only starting to be understood. As

with over-justification, we can make certain assumptions based on the

psychological literature and comparable experiences, but we lack

direct data on harmful effects.

One thing that we can and must take responsibility for up-front is

the potential for people to become addicted to — and

substantially influenced by — gamified experiences. Unlike our

peers in the casino industry who advocate a Randian view of free will,

and game designers who repeatedly claim that users can easily

distinguish fact from fiction, gamification shows us a more nuanced

view.

Games are the most powerful source of non-coercive influence in the

world, and are frequently designed with mild addiction and extreme flow in

mind. The latter effect in particular puts users into a state where

they are markedly more likely to accept what the system tells them,

and to respond to its stimuli (if only just to beat the level). We

cannot continue to argue the power of games to teach and engage on one

hand while ignoring the other side of the coin.

That’s why I advocate a voluntary code of conduct for gamification

design that vastly exceeds an ethics dialogue — let alone

standards of conduct — in games and gambling. At its heart, the

core concept is to allow users to make informed choices about their

engagement. It also means not using these techniques for anything that

would cause direct harm to users.

Without exception, every gamification project I’ve been involved

with has had good intentions, and I’ve seen little reason to worry

about nefarious actors. Game designers often like to see an epic

battle between good and evil — even where there isn’t one

— but that’s part of the charm. Even if there is no current

threat of harm from gamification designers, we should nonetheless have

the dialogue.

Fundamentally, gamification is a new industry and discipline that

is delivering unprecedented results across many different verticals.

The concept’s meteoric ascendance has given rise to a number of

debates, most of which have yet to capture meaningful issues in the

discussion. In outlining three viable concerns —

over-justification, total cost of ownership and addiction/compulsion

— I’ve endeavored to share some of the more substantive issues

that should be front and center in the dialogue.

Headed to OSCON in July? Be sure to catch Gabe’s session on using fun and engagement to build great software.

Related: