A few weeks ago, Tom Slee published “Seeing Like a Geek,” a thoughtful article on the dark side of open data. He starts with the story of a Dalit community in India, whose land was transferred to a group of higher cast Mudaliars through bureaucratic manipulation under the guise of standardizing and digitizing property records. While this sounds like a good idea, it gave a wealthier, more powerful group a chance to erase older, traditional records that hadn’t been properly codified. One effect of passing laws requiring standardized, digital data is to marginalize all data that can’t be standardized or digitized, and to marginalize the people who don’t control the process of standardization.

That’s a serious problem. It’s sad to see oppression and property theft riding in under the guise of transparency and openness. But the issue isn’t open data, but how data is used.

Jesus said “the poor are with you always” not because the poor aren’t a legitimate area of concern (only an American fundamentalist would say that), but because they’re an intractable problem that won’t go away. The poor are going to be the victims of any changes in technology; it isn’t surprisingly that the wealthy in India used data to marginalize the land holdings of the poor. In a similar vein, when Europeans came to North America, I imagine they told the natives “So, you got a deed to all this land?,” a narrative that’s still being played out with indigenous people around the world.

The issue is how data is used. If the wealthy can manipulate legislators to wipe out generations of records and folk knowledge as “inaccurate,” then there’s a problem. A group like DataKind could go in and figure out a way to codify that older generation of knowledge. Then at least, if that isn’t acceptable to the government, it would be clear that the problem lies in political manipulation, not in the data itself. And note that a government could wipe out generations of “inaccurate records” without any requirement that the new records be open. In years past the monied classes would have just taken what they wanted, with the government’s support. The availability of open data gives a plausible pretext, but it’s certainly not a prerequisite (nor should it be blamed) for manipulation by the 0.1%.

One can see the opposite happening, too: the recent legislation in North Carolina that you can’t use data that shows sea level rise. Open data may be the only possible resource against forces that are interested in suppressing science. What we’re seeing here is a full-scale retreat from data and what it can teach us: an attempt to push the furniture against the door to prevent the data from getting in and changing the way we act.

The digital publishing landscape

Slee is on shakier ground when he claims that the digitization of books has allowed Amazon to undermine publishers and booksellers. Yes, there’s technological upheaval, and that necessarily drives changes in business models. Business models change; if they didn’t, we’d still have the Pony Express and stagecoaches. O’Reilly Media is thriving, in part because we have a viable digital publishing strategy; publishers without a viable digital strategy are failing.

But what about booksellers? The demise of the local bookstore has, in my observation, as much to do with Barnes & Noble superstores (and the now-defunct Borders), as with Amazon, and it played out long before the rise of ebooks.

I live in a town in southern Connecticut, roughly a half-hour’s drive from the two nearest B&N outlets. Guilford and Madison, the town immediately to the east, both have thriving independent bookstores. One has a coffeeshop, stages many, many author events (roughly one a day), and runs many other innovative programs (birthday parties, book-of-the-month services, even ebook sales). The other is just a small local bookstore with a good collection and knowledgeable staff. The town to the west lost its bookstore several years ago, possibly before Amazon even existed. Long before the Internet became a factor, it had reduced itself to cheap gift items and soft porn magazines. So: data may threaten middlemen, though it’s

not at all clear to me that middlemen can’t respond competitively. Or that they are really threatened by “data”, as opposed to large centralized competitors.

There are also countervailing benefits. With ebooks, access is democratized. Anyone, anywhere has access to what used to be available only in limited, mostly privileged locations. At O’Reilly, we now sell ebooks in countries we were never able to reach in print. Our print sales overseas never exceeded 30% of our sales; for ebooks, overseas represents more than half the total, with customers as far away as Azerbaijan.

Slee also points to the music labels as an industry that has been marginalized by open data. I really refuse to listen whining about all the money that the music labels are losing. We’ve had too many years of crap product generated by marketing people who only care about finding the next Justin Bieber to take the “creative industry” and its sycophants seriously.

Privacy by design

Data inevitably brings privacy issues into play. As Slee points out,(and as Jeff Jonas has before him), apparently insignificant pieces of data can be put together to form a surprisingly accurate picture of who you are, a picture that can be sold. It’s useless to pretend that there won’t be increased surveillance in any forseeable future, or that there won’t be an increase in targeted advertising (which is, technically, much the same thing).

We can bemoan that shift, celebrate it, or try to subvert it, but we can’t pretend that it isn’t happening. We shouldn’t even pretend that it’s new, or that it has anything to do with openness. What is a credit bureau if not an organization that buys and sells data about your financial history, with no pretense of openness?

Jonas’s concept of “privacy by design” is an important attempt to address privacy

issues in big data. Jonas envisions a day when “I have more privacy features than you” is a marketing advantage. It’s certainly a claim I’d like to see Facebook make.

Absent a solution like Jonas’, data is going to be collected, bought, sold, and used for marketing and other purposes, whether it is “open” or not. I do not think we can get to Jonas’s world, where privacy is something consumers demand, without going through a stage where data is open and public. It’s too easy to live with the illusion of privacy that thrives in a closed world.

I agree that the notion that “open data” is an unalloyed public good is mistaken, and Tom Slee has done a good job of pointing that out. It underscores the importance of of a still-nascent ethical consensus about how to use data, along with the importance of data watchdogs, DataKind, and other organizations devoted to the public good. (I don’t understand why he argues that Apple and Amazon “undermine community activism”; that seems wrong, particularly in the light of Apple’s re-joining the EPEAT green certification system for their products after a net-driven consumer protest.) Data collection is going to happen whether we like it or not, and whether it’s open or not. I am convinced that private data is a public bad, and I’m less afraid of data that’s open. That doesn’t make it necessarily a good; that depends on how the data is used, and the people who are using it.

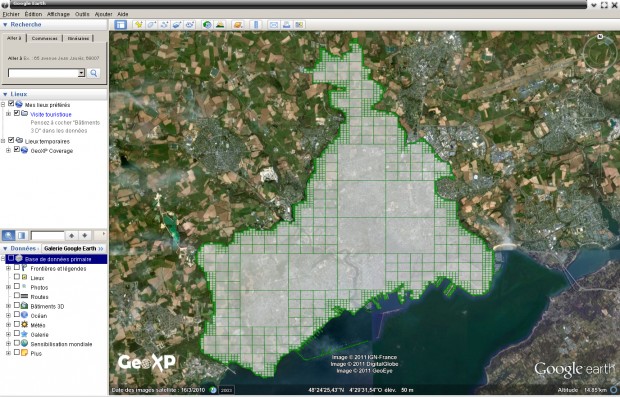

Image Credit: Steven La Roux