As interest in open data continues to grow around the world, cities have become laboratories for participatory democracy. They’re also ground zero for new experiments in spawning civic startups that deliver city services or enable new relationships between the people and city government. San Francisco was one of the first municipalities in the United States to embrace the city as a platform paradigm in 2009, with the launch of an open data platform.

Years later, the city government is pushing to use its open data to accelerate economic development. On Monday, San Francisco announced revised open data legislation to enable that change and highlighted civic entrepreneurs who are putting the city’s data to work in new mobile apps.

City staff have already published the revised open data legislation on GitHub. (If other cities want to “fork” it, clone away.) David Chiu, the chairman of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the city’s legislative body, introduced the new version on Monday and submitted it on Tuesday. A vote is expected before the end of the year.

Speaking at the offices of the Hatchery in San Francisco, Chiu observed that, by and large, the data that San Francisco has put out showed the city in a positive light. In the future, he suggested, that should change. Chiu challenged the city and the smartest citizens of San Francisco to release more data, figure out where the city could take risks, be more entrepreneurial and use data to hold the city accountable. In his remarks, he said that San Francisco is working on open budgeting but is still months away from getting the data that they need.

Rise of the CDO

This new version of the open data legislation will create a chief data officer (CDO) position, assign coordinators for open data in each city department, and make it clear in procurement language that the city owns data and retains access to it.

“Timelines, mandates and especially the part about getting them to inventory what data they collect are all really good,” said Luke Fretwell, founder of Govfresh, which covers open government in San Francisco. “It’s important that’s in place. Otherwise, there’s no way to be accountable. Previous directives didn’t do it.”

The city’s new CDO will “be responsible for sharing city data with the public, facilitating the sharing of information between City departments, and analyzing how data sets can be used to improve city decision making,” according to the revised legislation.

In creating a CDO, San Francisco is running a play from the open data playbooks of Chicago and Philadelphia. (San Francisco’s new CDO will be a member of the mayor’s staff in the budget office.) Moreover, the growth of CDOs around the country confirms the newfound importance of civic data in cities. If open government data is to be a strategic asset that can be developed for the public good, civic utility and economic value, it follows that it needs better stewards.

Assigning a coordinator in each department is also an acknowledgement that open data consumers need a point of contact and accountability. In theory, this could help create better feedback loops between the city and the cohort of civic entrepreneurs that this policy is aimed at stimulating.

Who owns the data?

San Francisco’s experience with NextBus and a conflict over NextMuni real-time data is a notable case study for other cities and states that are considering similar policies.

The revised legislation directs the Committee on Information Technology (COIT) to, within 60 days from the passage of the legislation, enact “rules for including open data requirements in applicable City contracts and standard contract provisions that promote the City’s open data policies, including, where appropriate, provisions to ensure that the City retains ownership of City data and the ability to post the data on data.sfgov.org or make it available through other means.”

That language makes it clear that it’s the city that owns city data, not a private company. That’s in line with a principle that open government data is a public good that should be available to the public, not locked up in a proprietary format or a for-pay database. There’s some nuance to the issue, in terms of thinking through what rights a private company that invests in acquiring and cleaning up government data holds, but the basic principle that the public should have access to public data is sound. The procurement practices in place will mean that any newly purchased system that captures structured data must have a public API.

Putting open data to work

Speaking at the Hatchery on Monday, Mayor Ed Lee highlighted three projects that each showcase open data put to use. The new Rec & Park app (iOS download), built by San Francisco-based startup Appallicious, enables citizens to find trails, dog parks, playgrounds and other recreational resources on a mobile device. “Outside” (iOS download), from San Francisco-based 100plus, encourages users to complete “healthy missions” in their neighborhoods. The third project, from mapping giant Esri, is a beautiful web-based visualization of San Francisco’s urban growth based upon open data from San Francisco’s planning departments.

The power of prediction

Over the past three years, transparency, accountability, cost savings and mobile apps have constituted much of the rationale for open data in cities. Now, San Francisco is renewing its pitch for the role of open data in job creation and combining increased efficiency and services.

Jon Walton, San Francisco’s chief information officer (CIO), identified two next steps for San Francisco in an interview earlier this year: working with other cities to create a federated model (now online at cities.data.gov) and using its own data internally to identify and solve issues. (San Francisco and cities everywhere will benefit from looking to New York City’s work with predictive data analytics.)

“We’re thinking about using data behind the firewalls,” said Walton. “We want to give people a graduated approach, in terms of whether they want to share data for themselves, to a department, to the city, or worldwide.”

On that count, it’s notable that Mayor Lee is now publicly encouraging more data sharing between private companies that are collecting data in San Francisco. As TechCrunch reported, the San Francisco government quietly passed a new milestone when it added to its open data platform private-sector datasets on pedestrian and traffic movement collected by Motionloft.

“This gives the city a new metric on when and where congestion happens, and how many pedestrians and vehicles indicate a slowdown will occur,” said Motionloft CEO Jon Mills, in an interview.

Mills sees opportunities ahead to apply predictive data analytics to life and death situations by providing geospatial intelligence for first responders in the city.

“We go even further when police and fire data are brought in to show the relation between emergency situations and our data,” he said. “What patterns cause emergencies in different neighborhoods or blocks? We’ll know, and the city will be able to avoid many horrible situations.”

Such data-sharing could have a real impact on department bottom lines: while “Twitter311” created a lot of buzz in the social media world, access to real-time transit data is what is estimated to have saved San Francisco more than $1 million a year by reducing the volume of San Francisco 311 calls by 21.7%.

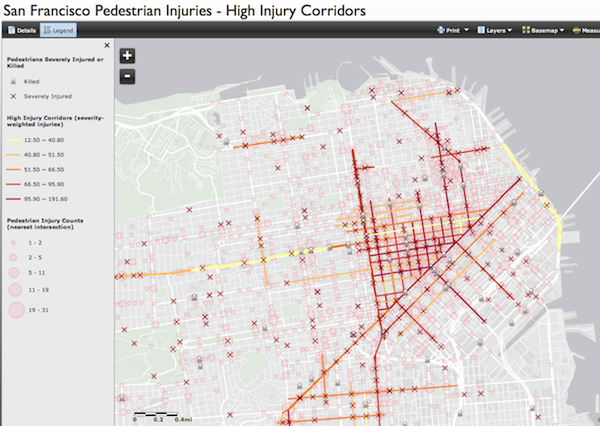

Open data visualization can also enable public servants to understand how city residents are interacting and living in an urban area. For instance, a map of San Francisco pedestrian injuries shows high-injury corridors that merit more attention.

Open data and crowdsourcing will not solve all IT ills

While San Francisco was an early adopter of open data, that investment hasn’t changed an underlying reality: the city government remains burdened by a legacy of dysfunctional tech infrastructure, as detailed in a report issued in August 2012 by the City and County of San Francisco.

“San Francisco’s city-wide technology governing structure is ineffective and poorly organized, hampered by a hands-off Mayor, a weak Committee on Information Technology, an unreliable Department of Technology, and a departmentalized culture that only reinforces the City’s technological ineffectiveness,” state the report’s authors.

San Francisco government has embraced technologically progressive laws and rhetoric, but hasn’t always followed through on them, from setting deadlines to reforming human resources, code sharing or procurement.

“Departments with budgets in the tens of millions of dollars — including the very agency tasked with policing government ethics — still have miles to go,” commented Gov 2.0 advocate Adriel Hampton and former San Francisco government staffer in an interview earlier this year.

Hampton, who has turned his advocacy to legal standards for open data in California and to working at Nationbuilder, a campaign software startup, says that San Francisco has used technology “very poorly” over the past decade. While he credited the city’s efforts in mobile government and recent progress on open data, the larger system is plagued with problems that are endemic in government IT.

Hampton said the city’s e-government efforts largely remain in silos. “Lots of departments have e-services, but there has been no significant progress in integrating processes across departments, and some agencies are doing great while others are a mess,” commented Hampton. “Want to do business in SF? Here’s a sea of PDFs.”

The long-standing issues here go beyond policy, in his view. “San Francisco has a very fragmented IT structure, where the CIO doesn’t have real authority, and proven inability to deliver on multi-departmental IT projects,” he said. As an example, Hampton pointed to San Francisco’s Justice Information Tracking System, a $25 million, 10-year project that has made some progress, but still has not been delivered.

“The City is very good at creating feel-good requirements for its vendors that simply result in compliant companies marking up and reselling everything from hardware to IT software and services,” he commented. “This makes for not only higher costs and bureaucratic waste, but huge openings for fraud. Contracting reform was the number one issue identified in the ImproveSF employee ideation exercise in 2010, but it sure didn’t make the press release.”

Hampton sees the need for two major reforms to keep San Francisco on a path to progress: empowering the CIO position with more direct authority over departmental IT projects, and reforming how San Francisco procures technology, an issue he says affects all other parts of the IT landscape. The reason city IT is so bad, he says, its that it’s run by a 13-member council. “[The] poor CIO’s hardly got a shot.”

All that said, Hampton gives David Chiu and San Francisco city government high marks for their recent actions. “Bringing in Socrata to power the open data portal is a solid move and shows commitment to executing on the open data principle,” he said.

While catalyzing more civic entrepreneurship is important, creating enduring structural change in how San Francisco uses technology will require improving how the city government collects, stores, consumes and releases data, along with how it procures, governs and builds upon technology.

On that count, Chicago’s experience may be relevant. Efforts to open government data there have led to both progress and direction, as Chicago CTO John Tolva blogged in January:

“Open data and its analysis are the basis of our permission to interject the following questions into policy debate: How can we quantify the subject-matter underlying a given decision? How can we parse the vital signs of our city to guide our policymaking? … It isn’t just app competitions and civic altruism that prompts developers to create applications from government data. 2011 was the year when it became clear that there’s a new kind of startup ecosystem taking root on the edges of government. Open data is increasingly seen as a foundation for new businesses built using open source technologies, agile development methods, and competitive pricing. High-profile failures of enterprise technology initiatives and the acute budget and resource constraints inside government only make this more appealing.”

Open data and job creation?

While realizing internal efficiencies and cost savings are key requirements for city CIOs, they don’t hold the political cachet of new jobs and startups, particularly in an election year. San Francisco is now explicitly connecting its release of open data to jobs.

“San Francisco’s open data policies are creating jobs, improving our city and making it easier for residents and visitors to communicate with government,” commented Mayor Lee, via email.

Lee is optimistic about the future, too: “I know that, at the heart of this data, there will be a lot more jobs created,” he said on Monday at the Hatchery.

Open data’s potential for job creation is also complemented by its role as a raw material for existing businesses. “This legislation creates more opportunities for the Esri community to create data-driven decision products,” said Bronwyn Agrios, a project manager at Esri, in an interview.

Esri, however, as an established cloud mapping giant, is in a different position than startups enabled by open data. Communications strategist Brian Purchia, the former new media director for former San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, points to Appallicious.

Appallicious “would not have been possible with [San Francisco’s] open data efforts,” said Purchia. “They have have hired about 10 folks and are looking to expand to other cities.”

The startup’s software drives the city’s new Rec & Park app, including the potential to enable mobile transactions in the next iteration.

“Motionloft will absolutely grow from our involvement in San Francisco open data,” said Motionloft CEO Mills. “By providing some great data and tools to the city of San Francisco, it enables Motionloft to develop solutions for other cities and government agencies. We’ll be hiring developers, sales people, and data experts to keep up with our plans to grow this nationwide, and internationally.”

The next big question for these startups, as with so many others in nearby Silicon Valley, is whether their initial successes can scale. For that to happen for startups that depend upon government data, other cities will not only need to open up more data, they’ll need to standardize it.

Motionloft, at least, has already moved beyond the Bay Area, although other cities haven’t incorporated its data yet. Esri, as a major enterprise provider of proprietary software to local governments, has some skin in this game.

“City governments are typically using Esri software in some capacity,” said Agrios. “It will certainly be interesting to see how geo data standards emerge given the rapid involvement of civic startups eagerly consuming city data. Location-aware technologists on both sides of the fence, private and public, will need to work together to figure this out.”

If the marketplace for civic applications based upon open data develops further, it could help with a key issue that has dogged the results of city app contests: sustainability. It could also help with a huge problem for city governments: the cost of providing e-services to more mobile residents as budgets continue to tighten.

San Francisco CIO Walton sees an even bigger opportunity for the growth of civic apps that go far beyond the Bay Area, if cities can coordinate their efforts.

“There’s lots of potential here,” Walton said. “The challenge is replicating successes like Open311 in other verticals. If you look at the grand scale of time, we’re just getting started. For instance, I use Nextbus, an open source app that uses San Francisco’s open data … If I have Nextbus on my phone, when I get off a plane in Chicago or New York City, I want to be able to use it there, too. I think we can achieve that by working together.”

If a national movement toward open data and civic apps gathers more momentum, perhaps we’ll solve a perplexing problem, mused Walton.

“In a sense, we have transferred the intellectual property for apps to the public,” he said. “On one hand, that’s great, but I’m always concerned about what happens when an app stops working. By creating data standards and making apps portable, we will create enough users so that there’s enough community to support an application.”

Related: