The map of the industrial Internet is still being drawn, which means the decisions we’re making about it now will determine the extent to which it shapes our world.

With that as a backdrop, Tim O’Reilly (@timoreilly) used his presentation at the recent Minds + Machines event to urge the industrial Internet’s architects to apply three key lessons from the Internet’s evolution. These three characteristics gave the Internet its ability to be open, to scale and to adapt — and if these same attributes are applied to the industrial Internet, O’Reilly believes this growing domain has the ability to “change who we are.”

Full video and slides from O’Reilly’s talk are embedded at the end of this piece. You’ll find a handful of insights from the presentation outlined below.

Lesson 1: Simplicity

“Standardize as little as possible, but as much as is needed so the system is able to evolve,” O’Reilly said.

To illustrate this point, O’Reilly drew a line between the simplicity and openness of TCP/IP, the creation and growth of the World Wide Web, and the emergence of Google.

“The Internet is fundamentally permission-less,” O’Reilly said. “Those of us who were early pioneers on the web, all we had to do was download the software and start playing. That’s how the web grew organically. So much more came from that.”

A nice side-effect of this model is that you can easily determine its success. “A new platform can be said to succeed when your customers and partners build new features before you do,” O’Reilly noted.

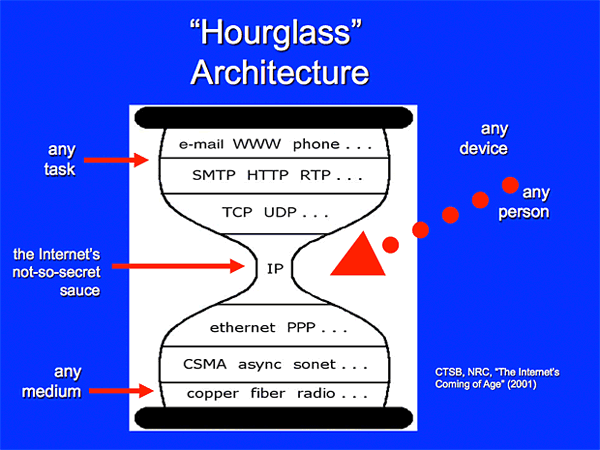

“The IP protocol did the smallest, necessary thing: it specified the format of the data that would be exchanged between machines. Everything else could vary, from the transport protocols and transport medium all the way to the kinds of applications and services that were exchanging that data. Jonathan Zittrain refers to this as the ‘hourglass architecture’ of the Internet.”

— Tim O’Reilly, “Lessons for the Industrial Internet,” slide 6

(The “simplicity” segment begins at the 1:43 mark in the accompanying video.)

Lesson 2: Generativity

“Create an architecture of participation that leads to unexpected innovations and discoveries, and builds a new ecosystem of companies that add value to the network,” O’Reilly explained.

O’Reilly pointed to two examples relevant to this lesson:

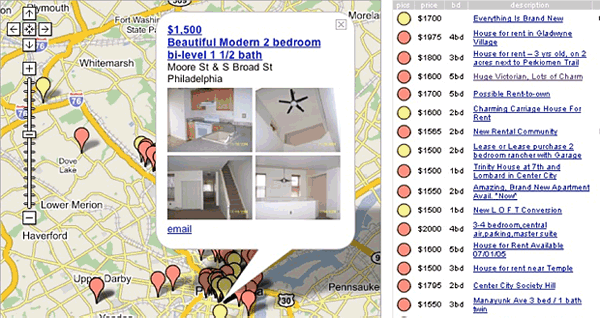

- Google Maps — Online mapping services were already common when Google launched its Maps service in 2005. So how did Google push to the front of the line? When hackers started mashing up Maps data with external sources, Google embraced those efforts and launched APIs. The result is a mapping platform that’s achieved ubiquity through accessibility. It’s unlikely anyone within Google could have anticipated the innovations that would come once the doors were thrown open.

- Apple’s App Store / the rise of Android — The first iPhone didn’t launch with an App Store. Third-party development at that point was limited to web apps. But Apple plotted a new course when it saw jailbreaking grow, and the company now oversees a marketplace with more than 700,000 applications. However, O’Reilly pointed to the rise of Android as evidence that Apple didn’t completely embrace a participatory architecture. “Apple didn’t learn the lesson well enough,” he said.

O’Reilly also noted that the industrial Internet’s considerable upside makes the need for participatory architecture vital. “I think this industrial Internet idea is so powerful and so right, that everybody is going to want to get on board. It’s going to be really important to figure out how you create an open systems approach to this. That doesn’t mean you can’t create enormous value for yourselves, but it’s super important to think about that aspect of it.”

“When Paul Rademacher reverse-engineered the format of Google’s new mapping app to create the first map mashup, HousingMaps.com, Google could have branded him a ‘hacker’ and tried to shut him down. Instead, they responded by opening up free APIs for developers. Other, more closed platforms were left in the dust, and Google Maps became the preferred mapping platform for the web.”

— Tim O’Reilly, “Lessons for the Industrial Internet,” slide 11

(This “generativity” segment begins at the 3:01 mark in the accompanying video.)

Lesson 3: Robustness

Build “the ability to tolerate failure and degrade gracefully rather than catastrophically,” O’Reilly said.

“Graceful failure” may sound like an excuse a parent uses to soothe a child’s bruised ego, but it’s actually a fundamental building block of the Internet.

As an example, O’Reilly said that one of the key innovations Tim Berners-Lee constructed when he developed the World Wide Web was the ability for anyone to create a hypertext link that didn’t resolve. A user would bump up against a 404 message if a link hit a dead end, yet everything would still function and the user could flow around the obstacle without the entire system crumbling.

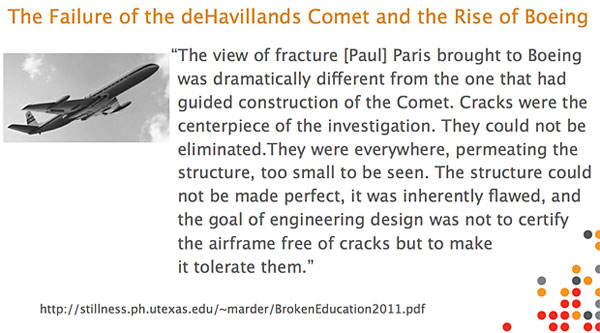

Now, you may think an innocuous 404 failure is a far cry from the failure of a massive chunk of industrial machinery. That’s not necessarily the case. O’Reilly told the story of a Boeing engineer who addressed catastrophic metal fatigue in airplanes through a form of graceful failure. “The right answer wasn’t to eliminate all the cracks,” O’Reilly said. “You had to figure out how to live with them.”

Bottom line: Whether we’re talking about hypertext or airliner materials, an embrace of robustness and graceful failure expands a domain’s possibilities. “One of the big lessons from the Internet is if you don’t know how to fail, you’ll never be able to scale,” O’Reilly said.

“While it may seem that this philosophy of the Internet is inappropriate for the highly engineered systems of the industrial Internet, I’ll remind you of the failure of de Havilland’s Comet in 1954 and the rise of Boeing as the dominant provider of commercial aircraft. Over the course of three years, three Comets fell out of the sky for initially unexplained reasons. It eventually became clear that the problem was metal fatigue. De Havilland tried to eliminate all cracks; Boeing learned to live with them.”

— Tim O’Reilly, “Lessons for the Industrial Internet,” slide 18

(This “robustness” segment begins at the 6:40 mark in the accompanying video.)

Full video: “Minds + Machines 2012: ‘Closing the Loop’ – Lessons of Data for the Industrial Internet”

Additional insights and discussion are contained in this video. The first 13 minutes features O’Reilly’s presentation, which is then followed by a panel discussion between O’Reilly, Paul Maritz of EMC, DJ Patil of Greylock Partners, Hilary Mason of bitly, and Matt Reilly of Accenture Management Consulting.

Slides: “Lessons for the Industrial Internet”

This is a post in our industrial Internet series, an ongoing exploration of big machines and big data. The series is produced as part of a collaboration between O’Reilly and GE.

Related industrial Internet coverage