When I went to the 2013 SXSW Interactive Festival to host a conversation with NPR’s Javaun Moradi about sensors, society and the media, I thought we would be talking about the future of data journalism. By the time I left the event, I’d learned that sensor journalism had long since arrived and been applied. Today, inexpensive, easy-to-use open source hardware is making it easier for media outlets to create data themselves.

“Interest in sensor data has grown dramatically over the last year,” said Moradi. “Groups are experimenting in the areas of environmental monitoring, journalism, human rights activism, and civic accountability.” His post on what sensor networks mean for journalism sparked our collaboration after we connected in December 2011 about how data was being used in the media.

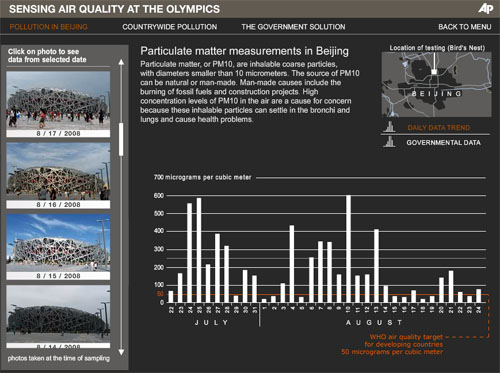

Associated Press visualization of Beijing air quality. See related feature.

At a SXSW panel on “sensoring the news,” Sarah Williams, an assistant professor at MIT, described how the Spatial Information Design Lab At Columbia University* had partnered with the Associated Press to independently measure air quality in Beijing.

Prior to the 2008 Olympics, the coaches of the Olympic teams had expressed serious concern about the impact of air pollution on the athletes. That, in turn, put pressure on the Chinese government to take substantive steps to improve those conditions. While the Chinese government released an index of air quality, explained Williams, they didn’t explain what went into it, nor did they provide the raw data.

The Beijing Air Tracks project arose from the need to determine what the conditions on the ground really were. AP reporters carried sensors connected to their cellphones to detect particulate and carbon monoxide levels, enabling them to report air quality conditions back in real-time as they moved around the Olympic venues and city.

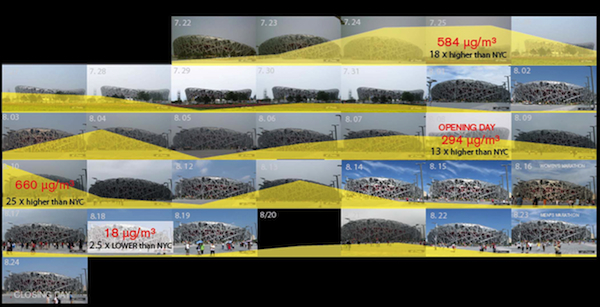

The sensor data helped the AP measure the effect of policy decisions that the Chinese government made, said Williams, from closing down factories to widespread shutdowns of different kinds of industries. The results from the sensor journalism project, which showed a decrease in particulates but conditions 12 to 25 times worse than New York City on certain days, were published as an interactive data visualization.

Associated Press mashup of particulate levels and photography at the Olympic stadium in Beijing over time.

This AP project is a prime example of how sensors, data journalism, and old-fashioned, on-the-ground reporting can be combined to shine a new level of accountability on official reports. It won’t be the last time this happens, either. Around the world, from the Amazon to Los Angeles to Japan, sensor data is now being put to use by civic media and journalists.

Sensing civic media

There are an increasing number of sensors in our lives, said John Keefe, a data news editor for WNYC, speaking at his SXSW panel in Austin. From the physical sensors in smartphones to new possibilities built with Arduino or Raspberry Pi hardware, Keefe highlighted how journalists could seize hold of new possibilities.

“Google takes data from maps and Android phones and creates traffic data,” Keefe said. “In a sense, that’s sensor data being used live in a public service. What are we doing in journalism like that? What could we do?”

The evolution of Safecast offers a glimpse of networked accountability, collecting and publishing radiation data through sensors, citizen science and the Internet. The project, which won last year’s Knight News Challenge on data, is now building the infrastructure to enable people to help monitor air quality in Los Angeles.

Sensor journalism is also being applied to make sense of the world in using remote sensing data and satellite imagery. The director of that project, Gustavo Faleiros, recently described how environmental reporting can be combined with civic media to collect data, with relevant projects in Asia, Africa and the Americas. For instance, Faleiros cited an environmental monitoring project led by Eric Paulos of the University of California at Berkeley’s Center for New Media, where sensors on taxis were used to gather data in Accra, Ghana.

Another direction that sensor data could be applied lies in social justice and education. At SXSW, Sarah Williams described [slides] how the Air Quality Egg, an open source hardware device, is being used to make an argument for public improvements. At the Cypress Hills Community School, kids are bringing the eggs home, measuring air quality and putting data online, said Williams.

Air Quality Eggs at Cypress Hill Community School.

“Health sensors are useful when they can compare personal real-time data against population-wide data,” said Nadav Aharony, who also spoke on our panel in Austin.

Aharony talked about how Behavio, a startup based upon his research on smartphones and data at MIT, has created funf, an open source sensing toolkit for Android devices. Aharony’s team has now deployed an integration with Dropbox that requires no coding ability to use.

According to Aharony, the One Laptop Per Child project is using funf in tablets deployed in Africa, in areas where there are no schools. Researchers will use funf as a behavioral tool to sense how children are interacting with the devices, including whether tablets are next to one another.

Just set up @openfunf‘s Funf in a Box on a phone to send motion+geo data to my @dropbox Couldn’t have been easier. funf.org

— John Keefe (@jkeefe) March 22, 2013

Sensing citizen science

While challenges lie ahead, it’s clear that sensors will be used to create data where there was none before. At SXSW, Williams described a project in Nairobi, Kenya, where cellphones are being used to map informal bus systems.

The Digital Matatus project is publishing the data into the General Transit Feed Standard, one of the most promising emerging global standards for transit data. “Hopefully, a year from now [we] will have all the bus routes from Nairobi,” Williams said.

Map of Matatus stops in Nairobi, Kenya

Data journalism has long depended upon official data released by agencies. In recent years, data journalists have begun scraping data. Sensors allow another step in that evolution to take place, where civic media can create data to inform the public interest.

Matt Waite, a professor of practice and head of the Drone Journalism Lab at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, joined the panel in Austin using a Google Hangout and shared how he and his students are experimenting with sensors to gather data for projects.

Journalists are going to run up against stories where no one has data, he said. “The old way was to give up,” said Waite. “I don’t think that’s the way to do it.”

Sensors give journalists a new, interesting way to enlist a distributed audience in gathering needed data, he explained. “Is it ‘capital N’ news? Probably not,” said Waite. “But it’s something people are really interested in. The easy part is getting a parts list together and writing software. The hard part is the creative process it takes to figure out what we are going to measure and what it means.”

In an interview with the Nieman Journalism Lab on sensor journalism, Waite also raised practical concerns with the quality of data collection that can be gathered with inexpensive hardware. “One legitimate concern about doing this is, you’re talking about doing it with the cheapest software you can find,” Waite told the Nieman Lab’s Caroline O’Donovan. “It’s not expertly calibrated. It’s not as sensitive as it possibly could be.”

Those are questions that will be explored practically in New York in the months ahead, when New York City’s public radio station will be collaborating with the Columbia School of Public Health to collect data about New York’s environmental conditions. They’ll put particulate detectors, carbon dioxide monitors, leg motion sensors, audio monitors, cameras and GPS trackers on bicycles and ride around the city collecting pollution data.

“At WNYC, we already do crowdsourcing, where we ask our audience to do something,” said Keefe. “What if we could get our audience to do something with this? What if you could get an audience to work with you to solve a problem?”

Keefe also announced the Cicada Project, where WNYC is inviting its listeners to build homemade sensors and track the emergence of cicadas this spring across New Jersey, New York and the Northeast region.

This cicada tracker project is a 21st century parallel to the role that birders have played for decades in the annual Christmas Bird Count, creating new horizons for citizen science and public media.

Update: WNYC’s public is responding in interesting ways that go beyond donations. On Twitter, Keefe highlighted the work of a NYC-based hacker, Guan, who was able to make a cicada tracker for $20, 1/4 the cost of WNYC’s kit.

@jkeefe <$20 cicada tracker (using crappy uncharacterized thermistor I had lying around). @johnmyleswhite twitter.com/guan/status/31…

— guan (@guan) March 22, 2013

Sensing challenges ahead

Just as civic technologists need to be mindful of “solutionism,” so too will data journalists need to be aware of the “sensorism” that exists in the health care world, as John Wilbanks pointed out this winter.

“Sensorism is rife in the sciences,” Wilbanks wrote. “Pick a data generation task that used to be human centric and odds are someone is trying to automate and parallelize it (often via solutionism, oddly — there’s an app to generate that data). What’s missing is the epistemic transformation that makes the data emerging from sensors actually useful to make a scientific conclusion — or a policy decision supposedly based on a scientific consensus.”

Anyone looking to practice sensor journalism will face interesting challenges, from incorrect conclusions based upon faulty data to increased risks to journalists carrying the sensors, to gaming or misreporting.

“Data accuracy is both a real and a perceived problem,” said Moradi at SXSW. “Third-party verification by journalists or other non-aligned groups may be needed.”

Much as in the cases of “drone journalism” and data journalism, context, usage and ethics have to be considered before you launch a quadcopter, fire up a scraper or embed sensors around your city. The question you come back to is whether you’re facing a new ethical problem or an old ethical problem with new technology, suggested Waite at SXSW. “The truth is, most ethical issues you can find with a new analogue.”

It may be, however, that sensor data, applied to taking a “social MRI” or other uses, may present us with novel challenges. For instance, who owns the data? Who can access or use it? Under what conditions?

A GPS device is a form of sensor, after all, and one that’s quite useful to law enforcement. While the Supreme Court ruled that the use of a GPS device for tracking a person without a warrant was unconstitutional, sensor data from cellphones may provide law enforcement with equal or greater insight into a target’s movements. Journalists may well face unexpected questions about protecting sources if their sensor data captures the movements or actions of a person of interest.

“There’s a lot of concern around privacy,” said Moradi. “What data can the government request? Will private companies abuse personal data for marketing or sales? Do citizens have the right to personal data held by companies and government?”

Aharony outlined many of the issues in a 2011 paper on stealing reality, exploring what happens when criminals become data scientists.

“It’s like a slow-moving attack if you attach yourself to someone’s communication,” said Aharony, in a follow-up interview in Austin. “‘iPhonegate‘ didn’t surprise people who know about mobile app data or how the cellular network is architected. Look at what happened to Path. You can make mistakes without meaning to. You have to think about this and encrypt the data.”

This post is part of our series investigating data journalism.