When I was about 16, I went to visit my grandfather in Denver, where he’d decided to retire. He moved there after spending 30 years in Midland, Michigan working for Dow Chemical. I guess he went west for the dry air. I don’t know if it was good for his lungs, but it sure didn’t go well with wool carpet. I shocked myself every time I touched something. Sometimes the spark would arc three inches from my finger tip to a door knob. There would be a visible flash and pop, and then a reflexive jump. It was a bit terrifying after a while. My grandfather, being an engineer, had figured a simple solution to that problem: he just touched every door knob with his key to ground himself before he opened it. It worked fine, but I didn’t remember to do it. Not once. But that’s not the point of this post.

One evening, we got to talking about his work at Dow and he showed me his patents. He was proud to show them to me, and I was proud of him. The fact that he had all those patents struck me as a testament to his ingenuity. He was smart, and the U.S. Government was acknowledging it in a most formal way.

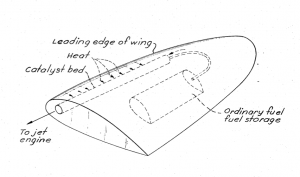

Most of his patents were about some chemical process or another, but one of them caught my imagination as particularly cool. He realized that the heat coming off of the leading edge of a high-speed aircraft could be used to pre-catalyze jet fuel. I loved airplanes (back then, I still wanted to fly jets), it seemed smart, and I think I just liked the cartoony nature of the drawing in the patent.

He worked for Dow, so naturally all of his work was assigned to the company. And really, that seemed fine to him, and to me. After all, to him that patent was probably less about the temporary grant of government-sponsored monopoly and more about the USPTO’s recognition of his intellect put to paper. It would have been nice for him if Dow had sold his invention to Boeing for lots of money, but it was sort of orthogonal to the intrinsic incentive framework he was working from.

As odd as this mindset seems to me now, it was a mindset I adopted explicitly at the time, and held onto implicitly for a long time after. That evening must have been important to me because I resolved then to patent some of my ideas some day. Years later in my career, when I was working for a small consulting firm, I started making patent applications with my colleagues.

And a while ago, many years after it was filed, this patent showed up — and I should have been thrilled. The idea was to use shared context as an input to routing algorithms, an idea I was super excited about, and that 16-year-old version of me would have been stoked that the USPTO saw enough value in it to grant a patent. The problem is that my relationship with patents is a lot more complicated now than it was then, and honestly, my first thought was “aw, shit.”

Jefferson was concerned about monopoly, a lot, and it took him a long time to come around to the idea of patents in those newly united states. He reluctantly changed his position when he realized that the surging industrialization of England would put us at a serious disadvantage if we were unable to keep up, but I don’t think he ever fully resolved the tension he felt between the need for innovation and his distaste for monopoly. He was probably right in his day to support patents, despite his concerns. Conditions change, however — today, software patents, in particular, have become little more than the re-enshrinement of the rentier in law, little different than a King’s Charter, and less useful.

And that was on my mind this morning when I read this. Especially this bit: “An IBM spokesman told Politico, ‘While we support what Mr. Goodlatte’s trying to do on trolls, if the CBM is included, we’d be forced to oppose the bill.'” … because, rents. But I can’t really be all that self-righteous about it when I hold a software patent too, can I?

There is an irony to this story. By the time Brian, Bill and I submitted our application, I had already soured on software patents. The only reason we submitted this one was because we were trying to build an open source community around the idea, and we wanted to protect the idea for the community we imagined building. We were building a software platform called “rvooz,” a contraction of rendezvous, and we launched a site called rvooz.org to host the code. We had high hopes for it and worked on it for more than a year, but unfortunately, it just didn’t get any uptake, neither with our market or with the community. C’est la vie.

The irony part comes later, when we sold our company to a much much larger company, and I tried (hard) to get that patent application killed. In fact, I thought I had gotten the application pulled, so imagine my surprise years later when it came through. So, now the patent exists, without the open source community it was designed to protect, and it’s owned by assignment to the kind of big company that sees patents as more of a protective moat than as a well of innovation.

Anyway, I guess the point of this post is one part to express disappointment at the turn of events that has led me to feel bad about achieving something my grandfather would have been proud of, and one part mea culpa. It bugs me that our patent is in the world, and I guess I felt I owed the world an explanation.