Editor’s note: This is an excerpt by Claire Rowland from our upcoming book Designing Connected Products. This excerpt is included in our curated collection of chapters from the O’Reilly Design library, Designing for the Internet of Things.

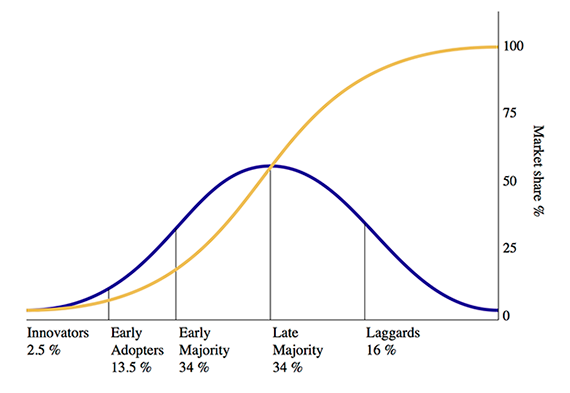

In 1962, the sociologist Everett Rogers introduced the idea of the technology lifecycle adoption curve, based on studies in agriculture. Rogers proposed that technologies are adopted in successive phases by different audience groups, based on a bell curve. This theory has gained wide traction in the technology industry. Successive thinkers have built upon it, such as the organizational consultant Geoffrey Moore in his book Crossing the Chasm.In Rogers’ model, the early market for a product is composed of innovators (or technology enthusiasts) and early adopters. These people are inherently interested in the technology and willing to invest a lot of effort in getting the product to work for them. Innovators, especially, might be willing to accept a product with flaws as long as it represents a significant or interesting new idea.

The next two groups — the early and late majority — represent the mainstream market. Early majority users might take a chance on a new product if they have seen it used successfully by others whom they know personally. Late majority users are skeptical and will adopt a product only after seeing that the majority of other people are already doing so. Both groups are primarily interested in what the product can do for them, unwilling to invest significant time or effort in getting it to work, and intolerant of flaws. Different individuals can be in different groups for different types of product. A consumer could be an early adopter of video game consoles, but a late majority customer for microwave ovens.

The diffusion of innovations according to Rogers. With successive groups of consumers adopting the new technology (shown in blue), its market share (shown in yellow) will eventually reach the saturation level.

Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Geoffrey Moore identified a “chasm” between the early adopter and early majority market (which he called visionaries and pragmatists, respectively). These groups have different needs and different buying habits. Mainstream customers don’t buy products for the same reasons as early adopters. They don’t perceive early adopters as having the same needs as themselves. Mainstream customers might be aware that early adopters are using the product, but this will not convince them to try it out themselves unless they see it as meeting their own, different, needs. So, products can be successful with an early market, yet fail to find a mainstream audience.

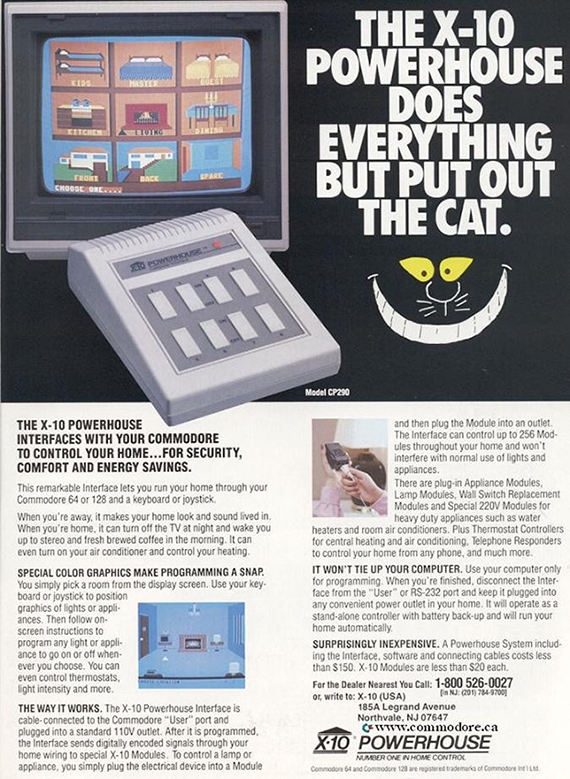

An example of this in the IoT space is the home automation market. Systems such as those based on the power line protocol X10 have been around for close to 40 years. (Early examples ran over electrical power lines and analogue phone lines). The example below, from 1986, shows a system that allowed users to program and remotely control their heating, lighting, and appliances over a (landline) phone. These are all applications that still seem novel and innovative to us; they would have excited the innovators of the 1980s even more.

Advertisement for X10 Powerhouse for the Commodore 64, from the January 1986 edition of Compute! Magazine. Image: commodore.ca.

However, home automation remained a niche market: it was expensive, and it required significant technical skill to set up and maintain. Even those mainstream consumers who had heard of home automation did not see much value in programming their heating, lighting, and appliances. Had it been more affordable or easier to use, more people might have been willing to try it out. But only now are consumers starting to see the utility of connected home products. This is arguably driven by the rise of the smartphone, giving us a metaphor for the “remote control for your life.”

What’s different about consumers?

Mainstream consumers are now more aware of connected devices, but they need to be convinced that these products will actually do something valuable for them. A product that appeals to an audience that loves technology for its own sake cannot simply be made easier to use or better looking. To appeal to a mass-market audience, a product might need to serve a different set of needs with a different value proposition. (Chapter 5, Understanding Users, covers learning about user needs and some of the special considerations you might encounter when designing for IoT.)

Mass-market product propositions have to spell out the value very clearly. Users will be subconsciously trying to estimate the benefit they’d get from your product as offset by the cost/effort involved in acquiring, setting up, and using it, and you need to be realistic about the amount of effort they will be prepared to invest in your product. The further along the curve they are, the more users need products with a clear and specific value proposition, and which require little effort to understand or use. And they have a very low tolerance for unreliability. Your product has made a promise to do something for them, and it must deliver on that promise.

This is not simply a question of lacking technical knowledge, and certainly not of users being dumb. That 10-step configuration process to set the heating schedule might seem trivial in the context of your single product. But it can feel overwhelmingly complex in the context of a busy life with many other more pressing concerns. For this reason, consumers tend to be most attracted to products that seem as if they will fit into their existing patterns of behavior and don’t require extra effort. For example, ATM cards and mobile phones were arguably successful because they reduced the need to plan ahead in daily activities (getting cash from the bank, or arranging to meet).