The problems caused by using the project paradigm to delivering software systems are severe. The effect of projects on downstream teams such as release and operations were, for my money, most succinctly articulated in Evan Bottcher’s article “PROJECTS ARE EVIL AND MUST BE DESTROYED“. The end result — complex, heterogeneous production environments that are hard to change or even keep running — is due to the forces Charles Betz identifies in Architecture and Patterns for IT Service Management, Resource Planning, and Governance: Making Shoes for the Cobbler’s Children:

Because it is the best-understood area of IT activity, the project phase is often optimized at the expense of the other process areas, and therefore at the expense of the entire value chain. The challenge of IT project management is that broader value-chain objectives are often deemed “not in scope” for a particular project, and projects are not held accountable for their contributions to overall system entropy.

Furthermore, bundling work up into projects combines low-value features with high-value features in order to deliver the maximum viable product that is the inevitable result of the large-batch death spiral. This occurs when product owners try and stuff as many features as possible into the next release so they don’t have to wait for the one after in order to get them delivered. As a result, the median cycle time for delivering features is often poorly correlated with their priority — a highly undesirable outcome.

Why do we stick with it? Because our budgeting processes are designed to operate on projects, and project managers and the PMO know how to deliver them.

Since these are clearly poor reasons, what should we do instead?

Continuous delivery. Resilience engineering. Performance optimization. And more.

Join the engineers, developers, operations pros, and technology leaders defining the modern, IT-driven business. Happening May 27–29, 2015.

Step 1: Unbundle projects

The first part of the answer is illustrated in detail in Joshua J. Arnold and Özlem Yüce’s paper Black Swan Farming using Cost of Delay, which describes how Maersk halved their median cycle time for delivering features while increasing quality and customer satisfaction. A key element in the transformation was unbundling projects into a dynamic feature list prioritized by Cost of Delay (the opportunity cost of failing to deliver the feature per unit time). This allowed stakeholders to triage and prioritize features quickly and to get the high value ones delivered faster.

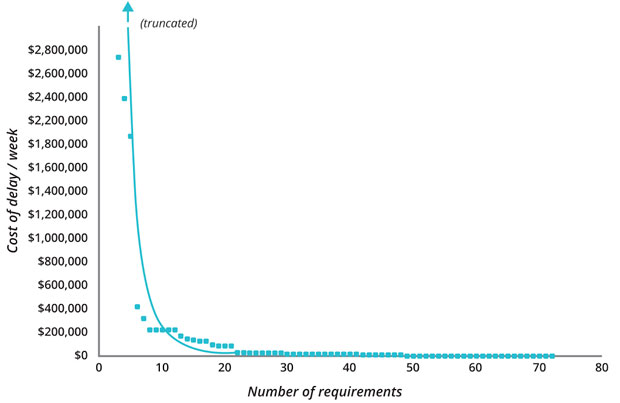

In this model the PMO changes its role. Instead of shepherding projects through the design, analysis, and approval phases, they get stakeholders together in one place and get them to triage incoming requirements, analyzing them to model their Cost of Delay and recording the assumptions they will inevitably make in coming to a dollar amount. This process is likely to reveal a small number of Black Swans — features which will provide significantly higher value than the rest. The distribution for Cost of Delay per feature after running this exercise for a single system is shown below (courtesy of Joshua J. Arnold and Özlem Yüce).

However even in this model, we are ultimately working within a Taylorist paradigm in which managers, analysts, and architects decide on the features to be built and the architecture to use, and engineers deliver according to the plan. This fails to make effective use of the creativity of people working in teams downstream of the planning process, and leads to a focus on using project management success criteria such as meeting our schedule, scope, quality, and cost estimates, rather than whether or not we delivered the expected value to customers and our organization.

Step 2: Explore the problem space together

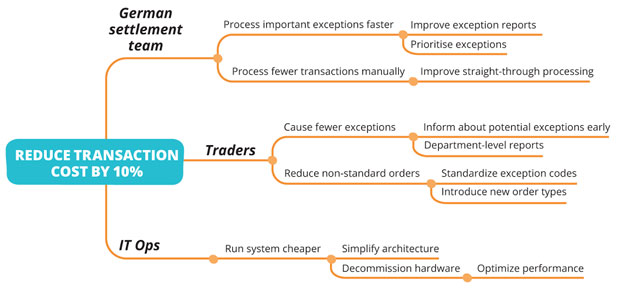

Every time we make a plan — whether a set of requirements, an architecture design, or process improvement work — we take the outcomes we want to create, consider the stakeholders, come up with some ideas to solve the problem, and then decide which option we will take. This process can be visualized as an Impact Map, as shown below.

In this example, courtesy of Gojko Adzic, author of Impact Mapping: Making a big impact with software products and projects, we take the customer or business outcome, then consider the stakeholders. In the next level we come up with options for how those stakeholders could achieve (or obstruct) the desired outcomes, and finally explore possible solutions.

What engineers and downstream teams receive in the form of a story, requirement, or task is a single path through the impact map. What if that path isn’t the one that provides the expected value?

Doing work that fails to achieve the expected outcome is one of the biggest sources of waste in enterprises. Research by Ronny Kohavi, who directed Amazon’s Data Mining and Personalization group before joining Microsoft as General Manager of its Experimentation Platform, reveals the “humbling statistics”: 60%–90% of ideas do not improve the metrics they were intended to improve. Based on experiments at Microsoft, 1/3 of ideas created a statistically significant positive change, 1/3 produced no statistically significant difference, and 1/3 created a statistically significant negative change on the business metric they were designed to improve. Delivering work without first validating whether it will create the desired outcome prevents us from doing more valuable work, and adds complexity to our systems which makes them harder to change and maintain.

Every idea for a feature, architectural decision, or process improvement should instead be treated as a hypothesis and tested, so we can find the most effective path to our goal. If the experiment we design shows that the expected outcome will not be achieved, we should abandon the idea and attempt another path instead.

In order for this to work, impact maps which describe the problem space need to be created by a cross-functional group including all relevant stakeholders. These maps should be shared across all teams, so that everyone knows the context of what they are working on, and the desired outcome.

Agreeing upon and sharing the measurable business and customer outcomes the team is working toward is a vital initial step, and it is the key to creating alignment at scale within enterprises. The job of managers is then to enable teams to run experiments to validate possible routes to the outcome, abandon the ideas that won’t work, and pursue those that do. Deploying this collaborative, scientific approach to product development, architectural evolution, and process improvement — and making it habitual — is the hallmark of a lean enterprise.

Editor’s note: if you’re yearning to break free of the traditional program management paradigm, check out Jez Humble’s Running Agile Programs at Scale webcast on March 19 at 10AM PT.

This post is part of our ongoing exploration into end-to-end optimization.

Public domain bubble wrap image via Pixabay.