Download a free copy of Python in Education. Editor’s note: this is an excerpt from Python in Education, a free report written by Nicholas Tollervey.

I am going to answer a very simple question: which features of the Python language itself make it appropriate for education? This will involve learning a little Python and reading some code. But don’t worry if you’re not a coder! This chapter will hopefully open your eyes to how easy it is to learn Python (and thus, why it is such a popular choice as a teaching language).

Code readability

When I write a to-do list on a piece of paper, it looks something like this:

Shopping Fix broken gutter Mow the lawn

This is an obvious list of items. If I wanted to break down my to-do list a bit further, I might write something like this:

Shopping:

Eggs

Bacon

Tomatoes

Fix broken gutter:

Borrow ladder from next door

Find hammer and nails

Return ladder!

Mow the lawn:

Check lawn around pond for frogs

Check mower fuel level

Intuitively, we understand that the main tasks are broken down into sub-tasks that are indented underneath the main task to which they relate. This makes it easy to see, at a glance, how the tasks relate to each other.

This is called scoping.

Indenting in this manner is also how Python organizes the various tasks defined in Python programs. For example, the following code simply says that there is a function called say_hello that asks the user to input their name, and then &mdsh; you guessed it — prints a friendly greeting:

def say_hello():

name = input('What is your name? ')

print('Hello, ' + name)

Here’s this code in action (including my user input):

What is your name? Nicholas Hello, Nicholas

Notice how the lines of code implementing the say_hello function are indented just like the to-do list. Furthermore, each instruction in the code is on its own line. The code is easy to read and understand: it is obvious which lines of code relate to each other just by looking at the way the code is indented.

Most other computer languages use syntactic symbols rather than indentation to indicate scope. For example, many languages such as Java, JavaScript, and C use curly braces and semicolons for this purpose.

Why is this important?

If, like me, you have taught students with English as an additional language or who have a special educational need such as dyslexia, then you will realize that Python’s intuitive indentation is something people the world over understand (no matter their linguistic background). A lack of confusing symbols such as ‘{‘, ‘}’ and ‘;’ scattered around the code also make it a lot easier to read Python code. Such indentation rules also guide how the code should look when you write it down — the students intuitively understand how to present their work.

Compared to most other languages, Python’s syntax (how it is written) is simple and easy to understand. For example, the following code written using the Perl programming language will look for duplicate words in a text document:

print "$.: doubled $_\n" while /\b(\w+)\b\s+\b\1\b/gi

Can you work out how Perl does this?

(In Perl’s defense, it is an amazingly powerful programming language with a different set of aims and objectives than Python. That’s the point — you wouldn’t try to teach a person how to read with James Joyce’s Ulysses, despite it being widely regarded as one of the top English-language novels of the 20th century.)

Put simply, because you don’t have to concentrate on how to read or write Python code, you can put more effort into actually understanding it. Anything that lowers the effort required to engage in programming is a good thing in an educational context (actually, one could argue that this is true in all contexts).

Obvious simplicity

The simple core concepts and knowledge required to write Python code will get you quite far. That they are easy to learn, use, and remember is another characteristic in Python’s favor. Furthermore, Python is an obvious programming language — it tries to do the expected thing and will complain if you, the programmer, attempt to do something clearly wrong. It’s also obvious in a second sense — it names various concepts using commonly understood English words.

Consider the following two examples:

In some languages, if you want to create a list of things, you have to use variously named constructs such as arrays, arraylists, vectors, and collections. In Python, you use something called a list. Here’s my to-do list from earlier written in Python:

todo_list = ['Shopping', 'Fix broken gutter', 'Mow the lawn']

This code assigns a list of values (strings of characters containing words that describe tasks in my to-do list) to an object named todo_list (which I can reuse later to refer to this specific list of items).

In some languages, if you want to create a data dictionary that allows you to store and look up named values (a basic key/value store), you’d use constructs called hashtables, associative arrays, maps, or tables. In Python, you use something called a dictionary. Here’s a data dictionary of a small selection of random capital cities:

capital_cities = {

'China': 'Beijing'

'Germany': 'Berlin',

'Greece': 'Athens',

'Russia': 'Moscow',

'United Kingdom': 'London',

}

I’ve simply assigned the dictionary to the capital_cities object. If I want to look up a capital city for a certain country, I reference the county’s name in square brackets next to the object named capital_cities:

capital_cities['China'] 'Beijing'

Many programming languages have data structures that work like Python’s lists and dictionaries; some of them do the obvious thing and call such constructs “lists” and “dictionaries”; some other languages make using such constructs as easy and obvious as Python (although many don’t). Python’s advantage is that it does all three of these things: it has useful data structures as a core part of the language, it gives them obvious names, and makes them extraordinarily easy to use. Such usefulness, simplicity, and clarity is another case of removing barriers to engaging with programming.

As mentioned earlier, Python also does the expected thing. For example, if I try to sum together an empty dictionary and an empty list (something that’s obviously wrong — evidence that I’ve misunderstood what I’m trying to do) Python will complain:

>>> {} + []

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'dict' and 'list'

This is simply telling me that I can’t use the “+” operand to sum a dictionary and a list. This is to be expected, rather obvious, and quite helpful.

Nevertheless, other languages try to be less strict and more forgiving of the programmer. While this may sound like a good idea, it means that faulty code like that attempted above will be executed without any error and cause uncertain results (after all, what is the answer of summing a dictionary and a list?). Here’s what the ubiquitous JavaScript language will do when you attempt to add the equivalent data structures (in JavaScript parlance, an object ‘{}’ and an array ‘[]’):

> {} + []

0

Of course, the answer is obviously zero!?!

Guess what happens if you try to sum an empty array with an object in JavaScript (we switch around the summed terms).

> [] + {}

"[object Object]"

I bet you were expecting a consistent result!

(Again, the caveat of JavaScript having a different set of aims and objectives to Python should be applied here.)

Learning, by its very nature, involves making mistakes and realizing that mistakes have been made. Only then can behavior be adjusted and progress made. If you’re learning to program using a language like JavaScript (that would rather make what appears to be a best guess at what you mean, rather than complain about an obvious error), then all sorts of mistakes will pass by unnoticed. Instead, you’ll either continue in your mistaken view of the programming world, or you’ll have to understand the rather complex and tortuous rules that JavaScript uses to cause {} + [] to equal 0 and [] + {} to equal "[object Object]" (itself, a difficult educational feat to pull off).

Python’s simplicity and obviousness encourages learners and professional developers alike to create understandable code. Understandable code is easier to maintain and less likely to contain bugs (because many bugs are caused by misunderstanding what the code is actually doing compared to what you mistakenly think it ought to be doing). Being able to simply state your ideas in code is a very powerful and empowering capability.

For example, consider an old-school text adventure game. Players wander around a world consisting of locations that have descriptions and exits to other locations. The program below very clearly and simply implements exactly that.

Most of the program consists of either comments to explain how it works or is a data dictionary that describes the game world. It is only the final block of code that actually defines the behavior of the game. It is my hunch, even if you’re not a programmer, that you’ll be able to get the gist of how it works.

"""

A very simple adventure game written in Python 3.

The "world" is a data structure that describes the game

world we want to explore. It's made up of key/value fields

that describe locations. Each location has a description

and one or more exits to other locations. Such records are

implemented as dictionaries.

The code at the very end creates a game "loop" that causes

multiple turns to take place in the game. Each turn displays

the user's location, available exits, asks the user where

to go next and then responds appropriately to the user's

input.

"""

world = {

'cave': {

'description': 'You are in a mysterious cave.',

'exits': {

'up': 'courtyard',

},

},

'tower': {

'description': 'You are at the top of a tall tower.',

'exits': {

'down': 'gatehouse',

},

},

'courtyard': {

'description': 'You are in the castle courtyard.',

'exits': {

'south': 'gatehouse',

'down': 'cave'

},

},

'gatehouse': {

'description': 'You are at the gates of a castle.',

'exits': {

'south': 'forest',

'up': 'tower',

'north': 'courtyard',

},

},

'forest': {

'description': 'You are in a forest glade.',

'exits': {

'north': 'gatehouse',

},

},

}

# Set a default starting point.

place = 'cave'

# Start the game "loop" that will keep making new turns.

while True:

# Get the current location from the world.

location = world[place]

# Print the location's description and exits.

print(location['description'])

print('Exits:')

print(', '.join(location['exits'].keys()))

# Get user input.

direction = input('Where now? ').strip().lower()

# Parse the user input...

if direction == 'quit':

print('Bye!')

break # Break out of the game loop and end.

elif direction in location['exits']:

# Set new place in world.

place = location['exits'][direction]

else:

# That exit doesn't exist!

print("I don't understand!")

A typical “game” (including user input) looks something like this:

$ python adventure.py You are in a mysterious cave. Exits: up Where now? up You are in the castle courtyard. Exits: south, down Where now? south You are at the gates of a castle. Exits: south, north, up Where now? hello I don't understand! You are at the gates of a castle. Exits: south, north, up Where now? quit Bye!

Furthermore, from an educational point of view, this simple adventure game can be modified in all sorts of interesting and obvious ways by learners: adding objects to the world, creating puzzles, adding more advanced commands, and so on. In fact, there are opportunities for cross-curricular work with other disciplines. Playing such a game is a form of interactive fiction — perhaps the English department could help the students come up with more than just the bare-bones descriptions of the original?

Open extensibility

Despite the powerful simplicity of the core language, programmers often need to reuse existing library modules of code to achieve a common task. A library module is like a recipe book of instructions for carrying out certain related tasks. It means programmers don’t have to start from scratch or reinvent the wheel every time they encounter a common problem.

While most programming languages have mechanisms to write and reuse libraries of code, Python is especially blessed in having a large and extensive standard library (built into the core language) as well as a thriving ecosystem of third-party modules.

For example, a common task is to retrieve data from a website. We can use the requests third-party module to download Web pages using Python:

>>> import requests

>>> response = requests.get('http://python.org/')

>>> response.ok

True

>>> response.text[:42]

'<!doctype html>\n<!--[if lt IE 7]> <html '

(This code tells Python that we want to use the requests library, gets the HTML for Python’s home page, checks that the response was a success [it was] and displays the first 42 characters of the resulting HTML document.)

Some modules, such as requests, do one thing and do it exceptionally well. Other modules are organized into large libraries to create application frameworks that solve many of the repetitive tasks needed when writing common types of application.

For example, Django is an application framework for writing Web applications (as used by Mozilla, The Guardian, National Geographic, NASA, and Instagram, among others). Django looks after common tasks such as modelling data, interacting with a database, writing templates for Web pages, security, scalability, deciding where to put business logic, and so on. Because this has already been taken care of by Django, developers are able to concentrate on the important task of designing websites and implementing business logic.

Many languages have extensive code libraries and application frameworks, but Python’s strength is in its broad reach. SciPy and NumPy are used by scientists and mathematicians, NLTK (the Natural Language Tool Kit) is used by linguists parsing text, Pandas is used extensively by statisticians, and OpenStack is used to organize and control cloud-based computing resources. The list goes on and on.

Teaching a language that has such extensive real-world use has an obvious benefit: learners acquire a skill in a programming language that has real economic value.

Another aspect of being openly extensible is that Python is an open source project. Anyone can take part in developing the language by submitting bug reports or patches to the core developers (led by Guido van Rossum himself). There is also a well-understood and simple process by which new features of the language are proposed and implemented: the Python Enhancement Proposals (PEPs). In this way, the language is developed in full view of the community that uses it, with the opportunity for the community to inform and guide its future development. This process is explained in great detail by PEP 1.

Cross-platform runability

Python is a platform-agnostic language: it works on Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, Linux, and many other operating systems and devices. It’s even possible to have Python as a service through websites such as Python Anywhere.

This is important in an educational context because Python works on the computers used in schools. Students can also use it on the computers they have at home, no matter the make or model they may own. Furthermore, Python, as a service provided via a website, is an excellent solution to the problem of the infamously troll-like school system administrators who won’t let teachers install anything other than Microsoft Office on school PCs. Users simply point their browser at a website, and they are presented with a fully functional Python development environment without having to install any additional software.

As we have seen, Python also works on small-form devices, such as the Raspberry Pi. It even runs on microcontrollers — small, low-powered chips designed to run within embedded devices, appliances, remote controls, and toys (among other things).

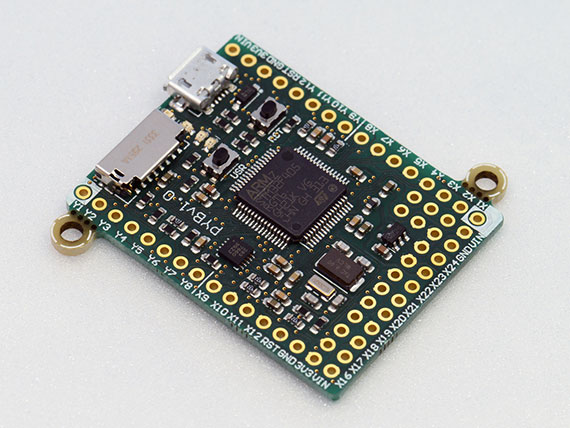

The MicroPython project has created a pared-down version of Python 3 that is optimized for such devices, and provides a small electronic circuit board that runs such a svelte version of Python:

A MicroPython board (about the same size as a postage stamp).

This very simple Python-based operating system can be used as the basis for all sorts of interesting and fun electronic projects. Add-ons for the board include an LCD display screen, speaker and microphone, and motors. It is a relatively easy task to build a simple robot with such a device.

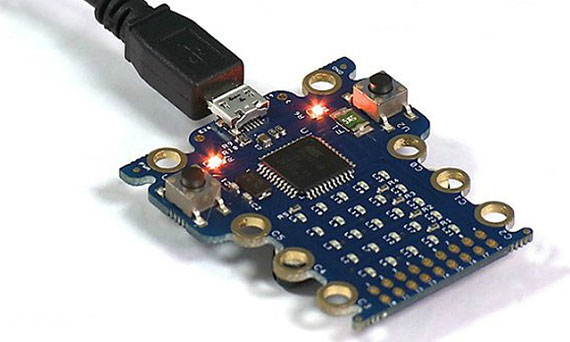

More recently, the BBC announced the MicroBit project, a small battery-powered programmable device for children. One million of the devices will be given away to 11-year-olds in the UK at the start of the new academic year in September 2015. It will also be on sale to the public.

The MicroBit fastens to clothing and has a couple of buttons and an LED matrix that displays scrolling text and images. Just like the Raspberry Pi and Micro Python board, it has the ability to interact with other devices via I/O connections.

Python is one of three supported languages for programming the MicroBit.

A prototype of the BBC’s MicroBit programmable device for children.

The important educational advantage is continuity.

By learning Python, a student has access to all sorts of fun and interesting platforms that can be explored using tools and code they’re familiar with. Because Python runs on so many platforms, it is feasible to write code for one device and, assuming it doesn’t use device-specific code and run within hardware constraints, it should run on many others.

Humanity

While not a strict feature of the language, Python’s community, history, and philosophy often shines through code written in Python.

The odd Monty Python reference (the website that hosts third-party Python modules is called the Cheese Shop after the sketch about a cheese shop with no cheese), a playful sense of fun (for instance, “the PyPy project” is so named because it is a high-performance version of Python written in Python), and other apparent eccentricities bestow upon Python the appearance of an approachable and interesting language. It’s obviously used by humans for humans rather than being an abstract tool for esoterics.

Python’s community is a friendly and diverse bunch. It is to this community of developers, teachers, and students that I want to turn in the next chapter.

Put simply, the Python community is the secret weapon of its success.