Download a free copy of “The New Design Fundamentals” ebook, a curated collection of chapters from our Design library. Note: this post is an excerpt from “Design Sprint,” by Richard Banfield, C. Todd Lombardo, and Trace Wax, which is included in the curated collection.

A Design Sprint is a flexible product design framework that serves to maximize the chances of making something people want. It is an intense effort conducted by a small team, where the results will set the direction for a product or service.The Design Sprint consists of five discrete phases:

- Understand (review background and user insights)

- Diverge (brainstorm what’s possible)

- Converge (rank solutions, pick one)

- Prototype (create a minimum viable concept)

- Test (validate with users)

A Design Sprint reduces the risk of downstream mistakes and generates vision-led goals the team can use to measure their success. For the purpose of this book, we’ll focus on digital products since our direct experience lies in that arena, though the Design Sprint has roots in gaming and architecture, and many industries have employed them successfully.

Uses of a Design Sprint

At the beginning of a project, you might use a Design Sprint to initiate a change in process or start the innovation of a product concept. This works well when you’re exploring opportunities with the goal of coming up with original concepts that ultimately will be tested in the real world. For example, if we need to understand how young parents would buy health care products online.

In the middle of a project, you might use a Design Sprint to start a new cycle of updates, expanding on an existing concept or exploring new ways to use an existing product. One such example that we worked with was a marketing data company that realized that the data they gathered might be useful to other market segments. Building a prototype gave them the validation they needed and prompted a deeper investment into that product segment, which ultimately was rewarded with a significant increase in sales.

For a mature project, the Design Sprint can also be used to test a single feature or subcomponent of a product. This allows you to focus in on an aspect of the design. For example, your team might need to know what improvements can be made to the onboarding process. Using the Design Sprint to discover the pros and cons of a new onboarding channel could give you granular insights into a high return part of the product experience.

However you use it, the Design Sprint brings clarity to your roadmap to kickstart and obtain initial validation for almost any new product-design-related work.

How the Design Sprint came to be

The term “sprint” comes from the world of Agile, and it describes a short period of time, typically 1-4 weeks, set aside to accomplish a focused goal. The Design Sprint is no different. It uses the original concept of the sprint to describe a period of time dedicated to working on the necessary design thinking. This time-bounded paradigm is critical to the success of the Design Sprint. “Timeboxing,” as it’s sometimes called, is essential to driving the right types of behavior from the participants. It’s not just important in speeding up the product design and development process; it takes advantage of core parts of our human nature — energy economy and social collaboration.

Going way back, the term “charrette” was used to describe any collaborative workshop session amongst designers, and design thinking frameworks from Stanford’s d.school emerged as a way to apply more structure to this concept. Industrial product design firms like IDEO developed short-cycle design sessions called Deep Dives, which built on the design charrette concept that borrowed from Stanford’s d.school.

IDEO’s most famous example is the shopping cart deep dive, which appeared on Nightline in 1999. The team pushed back on age-old mythologies about how design gets done and brought a multidisciplinary team together to brainstorm, research, prototype, and obtain user feedback that went from an idea to a working model in four days. By collapsing the time constraints, these designers were essentially holding a gun to their heads and forcing themselves to come up with better solutions in less time.

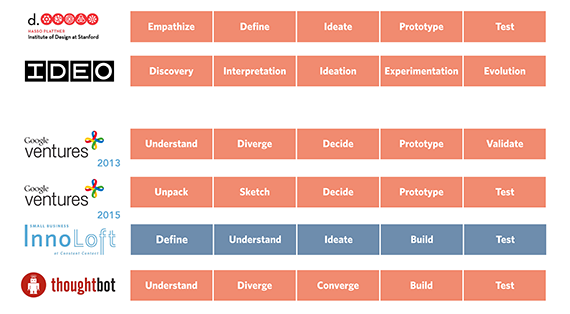

The influence of industrial design and software design was the genesis, but it was the emergence of digital product design that brought on a more formal framework for testing ideas out in the wild. Several organizations started to converge upon similar processes with similarly named phases:

Slide image courtesy of Richard Banfield, C. Todd Lombardo, and Trace Wax.

Although there have been company-specific versions of this approach used over the last decade, it was the work of Jake Knapp at Google Ventures (GV) that brought them to a broader audience.

GV invests in startups, and at times, those startups would need product-design advice to align their teams. To help with this, GV would send a designer for a week to the startup. As it turns out, these processes have five phases, one for each day of that week. The structure and time constraint proved useful. Lo and behold, the Design Sprint was born.

Created for startups, useful for enterprises

Startups are notoriously fast-moving environments that value speed to market over almost everything else. This commitment to speed gives them an advantage but also risks leaving out a lot of the essential thinking and testing required to build a truly useful product. Too many products go to market without customer validation. How do you maintain the speed while including the necessary research and design thinking? Many startups in the Constant Contact InnoLoft Program cite a Design Sprint as one of the most valuable parts of their participation.

Enterprises that have well-established processes may also look to a Design Sprint as a way to accelerate their product design and development so they can work more like a fast-moving startup. The accelerated learning can give the enterprise an advantage and also reduce the amount of resource investments for exploration of product ideas and concepts. Spending three to five days on a project idea to see if it makes sense to move forward is better than working three to five months, then finding it would be better to not have proceeded at all.

Any product or product feature will be validated or invalidated. You can do that validation, or let the market do it. Which do you think will be less expensive?

Success = time and money saved + minds blown

You can’t change what you can’t measure, right? One of the biggest questions we initially faced when implementing Design Sprints in our organizations was, “How do you measure the success of a Design Sprint?” In our experience, we had a few things we would measure, and often it was the absence of something that we were measuring. For example how do you measure the amount of time you won’t spend on bad product development? How much money will you save by not investing in a product that will make less ROI? Those questions point toward future gains by not spending some difficult-to-calculate amount of time or money. How do you measure the absence of a failed product?

“There’s no way you’re not going to save yourself time and money. Because the way these deals usually work is to go out and build things and just invest thousands of dollars and all this time, and then, find out that it falls flat. There is no testing done, no exploration done with end users,” remarked Dana Mitrof-Silvers, a design thinking consultant who works with many non-profits, such as the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. She measures the success of a Design Sprint by the ideas generated. “While ideas aren’t usually the problem, most organizations find themselves with an excess of ideas, validated ideas, and the execution is what’s missing.”

In many cases, a Design Sprint will lead you to something that gets initial user validation, where the next steps are defined. You’ll have reduced risk by doing some validation early, and develop next steps faster than would have otherwise been possible. Character Lab had a Design Sprint like this with thoughtbot. In a week, a large group of diverse stakeholders from an educational nonprofit got on the same page about what would be built, and remarked upon how quickly they reached agreement. Teachers and students were excited about the prototype they saw and couldn’t wait to use it. What we needed to build was clear and could proceed unimpeded at a good clip, which was very much needed given the size of the app and a shoestring nonprofit budget.

What makes the Design Sprint approach more effective is the structured, time-constrained framework with the right exercises.

Sometimes issues come to light that require clear changes in your product, and you can fix those things and plan additional research. For example, thoughtbot did a Design Sprint for Tile to optimize their mobile app design to help you find keys with a device attached. In the Sprint, we found that making the device beep louder helped people find keys three times faster than with anything we could do to the app. We iterated based on all the learnings and continued additional research sessions in the following weeks.

Design Sprints can help prevent you from building the wrong thing, even when your customers say it’s the right thing. Larissa Levine from the Advisory Board Company suggested a Design Sprint is successful if it guides you toward building the right product feature. She explained, “Product marketing wants to sell this one feature and says, ‘let’s build XYZ because we heard that the user said they wanted XYZ,’ when actually, that’s not the problem at all. They think they want XYZ, but it’s not it at all. So, you end up building the wrong thing.”

Sometimes a Design Sprint can get rid of those preconceived notions. Michael Webb, co-founder of InnoLoft startup resident itsgr82bme, entered a Design Sprint with a clear idea in his head about using APIs as a means for connecting their family event calendars with other sites’ event listings. During the sprint, he realized this could be done without using any APIs at all. He ended the sprint in a very different place.

Lastly, a Design Sprint can stop you from building any product at all. Marc Guy, co-founder and CEO of FAZE-1, also went through a Design Sprint at the InnoLoft. The sprint made him realize his company needed to stop building a product and instead go out and talk to customers. Product invalidated! Their business has shifted significantly as they then focused on the customer development.

Each Design Sprint will have its own needs and idiosyncrasies, and you’ll have to determine up-front what’s best for your project. Any good design-thinking process might help identify the real problem in each of these cases. What makes the Design Sprint approach more effective is the structured, time-constrained framework with the right exercises. This will force the team to make decisions and validate ideas faster than most methodologies.

Takeaways

- A Design Sprint has five phases: Understand, Diverge, Converge, Prototype, and Test. The names of these phases may vary from company to company, but the overall ethos remains the same: a time-boxed design cycle completed in a collaborative fashion with real user input.

- The focus of a Design Sprint is to get the validation needed to maximize the chances of creating something people want.

- The process is very flexible and can adapt to different teams and needs.

- Sprints can be measured in different ways, from the number of “good” ideas generated, team alignment, company direction, and even halting a project.