"bioengineering" entries

Smart collaborations beget smart solutions

Software developers and hardware engineers team up with biologists to address laboratory inefficiencies.

Download a free copy of the new edition of BioCoder, our newsletter covering the biological revolution.

Following the Synthetic Biology Leadership Excellence Accelerator Program (LEAP) showcase, I met with fellows Mackenzie Cowell, co-founder of DIYbio.org, and Edward Perello, co-founder of Desktop Genetics. Cowell and Perello both wanted to know what processes in laboratory research are inefficient and how we can eliminate or optimize them.One solution we’re finding promising is pairing software developers and hardware engineers with biologists in academic labs or biotech companies to engineer small fixes, which could result in monumental increases in research productivity.

An example of an inefficient lab process that has yet to be automated is fruit fly — Drosophila — manipulation. Drosophila handling and maintenance is laborious, and Dave Zucker and Matt Zucker from Flysorter are developing a technology using computer vision and machine learning software to automate these manual tasks; the team is currently engineering prototypes. This is a perfect example of engineers developing a technology to automate a completely manual and extremely tedious laboratory task. Check them out, and stay tuned for an article from them in the October issue of BioCoder. Read more…

BioBuilder: Rethinking the biological sciences as engineering disciplines

Moving biology out of the lab will enable new startups, new business models, and entirely new economies.

Buy “BioBuilder: Synthetic Biology in the Lab,” by Natalie Kuldell PhD., Rachel Bernstein, Karen Ingram, and Kathryn M. Hart.

What needs to happen for the revolution in biology and the life sciences to succeed? What are the preconditions?

I’ve compared the biorevolution to the computing revolution several times. One of the most important changes was that computers moved out of the lab, out of the machine room, out of that sacred space with raised floors, special air conditioning, and exotic fire extinguishers, into the home. Computers stopped being things that were cared for by an army of priests in white lab coats (and that broke several times a day), and started being things that people used. Somewhere along the line, software developers stopped being people with special training and advanced degrees; children, students, non-professionals — all sorts of people — started writing code. And enjoying it.

Biology is now in a similar place. But to take the next step, we have to look more carefully at what’s needed for biology to come out of the lab. Read more…

Democratizing biotech research

The O'Reilly Radar Podcast: DJ Kleinbaum on lab automation, virtual lab services, and tackling the challenges of reproducibility.

The convergence of software and hardware, and the growing ubiquitousness of the Internet of Things is affecting industry across the board, and biotech labs are no exception. For this Radar Podcast episode, I chatted with DJ Kleinbaum, co-founder of Emerald Therapeutics, about lab automation, the launch of Emerald Cloud Laboratory, and the problem of reproducibility.

Kleinbaum and his co-founder Brian Frezza started Emerald Therapeutics to research cures for persistent viral infections. They didn’t set out to spin up a second company, but their efforts to automate their own lab processes proved so fruitful, they decided to launch a virtual lab-as-a-service business, Emerald Cloud Laboratory. Kleinbaum explained:

“When Brian and I started the company right out of graduate school, we had this platform anti-viral technology, which the company is still working on, but because we were two freshly minted nobody Ph.D.s, we were not going to be able to raise the traditional $20 or $30 million that platform plays raise in the biotech space.

“We knew that we had to be much more efficient with the money we were able to raise. Brian and I both have backgrounds in computer science. So, from the beginning, we were trying to automate every experiment that our scientists ran, such that every experiment was just push a button, walk away. It was all done with process automation and robotics. That way, our scientists would be able to be much more efficient than your average bench chemist or biologist at a biotech company.

“After building that system internally for three years, we looked at it and realized that every aspect of a life sciences laboratory had been encapsulated in both hardware and software, and that that was too valuable a tool to just keep internally at Emerald for our own research efforts. Around this time last year, we decided that we wanted to offer that as a service, that other scientists, companies, and researchers could use to run their experiments as well.” Read more…

Bringing an end to synthetic biology’s semantic debate

The O'Reilly Radar Podcast: Tim Gardner on the synthetic biology landscape, lab automation, and the problem of reproducibility.

Editor’s note: this podcast is part of our investigation into synthetic biology and bioengineering. For more on these topics, download a free copy of the new edition of BioCoder, our quarterly publication covering the biological revolution. Free downloads for all past editions are also available.

Tim Gardner, founder of Riffyn, has recently been working with the Synthetic Biology Working Group of the European Commission Scientific Committees to define synthetic biology, assess the risk assessment methodologies, and then describe research areas. I caught up with Gardner for this Radar Podcast episode to talk about the synthetic biology landscape and issues in research and experimentation that he’s addressing at Riffyn.

Defining synthetic biology

Among the areas of investigation discussed at the EU’s Synthetic Biology Working Group was defining synthetic biology. The official definition reads: “SynBio is the application of science, technology and engineering to facilitate and accelerate the design, manufacture and/or modification of genetic materials in living organisms.” Gardner talked about the significance of the definition:

“The operative part there is the ‘design, manufacture, modification of genetic materials in living organisms.’ Biotechnologies that don’t involve genetic manipulation would not be considered synthetic biology, and more or less anything else that is manipulating genetic materials in living organisms is included. That’s important because it gets rid of this semantic debate of, ‘this is synthetic biology, that’s synthetic biology, this isn’t, that’s not,’ that often crops up when you have, say, a protein engineer talking to someone else who is working on gene circuits, and someone will claim the protein engineer is not a synthetic biologist because they’re not working with parts libraries or modularity or whatnot, and the boundaries between the two are almost indistinguishable from a practical standpoint. We’ve wrapped it all together and said, ‘It basically advances in the capabilities of genetic engineering. That’s what synthetic biology is.'”

Beyond lab folklore and mythology

What the future of science will look like if we’re bold enough to look beyond centuries-old models.

Editor’s note: this post is part of our ongoing investigation into synthetic biology and bioengineering. For more on these areas, download the latest free edition of BioCoder.

Over the last six months, I’ve had a number of conversations about lab practice. In one, Tim Gardner of Riffyn told me about a gene transformation experiment he did in grad school. As he was new to the lab, he asked two more experienced scientists for their protocol: one said it must be done exactly at 42 C for 45 seconds, the other said exactly 37 C for 90 seconds. When he ran the experiment, Tim discovered that the temperature actually didn’t matter much. A broad range of temperatures and times would work.

In an unrelated conversation, DJ Kleinbaum of Emerald Cloud Lab told me about students who would only use their “lucky machine” in their work. Why, given a choice of lab equipment, did one of two apparently identical machines give “good” results for a some experiment, while the other one didn’t? Nobody knew. Perhaps it is the tubing that connects the machine to the rest of the experiment; perhaps it is some valve somewhere; perhaps it is some quirk of the machine’s calibration.

The more people I talked to, the more stories I heard: labs where the experimental protocols weren’t written down, but were handed down from mentor to student. Labs where there was a shared common knowledge of how to do things, but where that shared culture never made it outside, not even to the lab down the hall. There’s no need to write it down or publish stuff that’s “obvious” or that “everyone knows.” As someone who is more familiar with literature than with biology labs, this behavior was immediately recognizable: we’re in the land of mythology, not science. Each lab has its own ritualized behavior that “works.” Whether it’s protocols, lucky machines, or common knowledge that’s picked up by every student in the lab (but which might not be the same from lab to lab), the process of doing science is an odd mixture of rigor and folklore. Everybody knows that you use 42 C for 45 seconds, but nobody really knows why. It’s just what you do.

Despite all of this, we’ve gotten fairly good at doing science. But to get even better, we have to go beyond mythology and folklore. And getting beyond folklore requires change: changes in how we record data, changes in how we describe experiments, and perhaps most importantly, changes in how we publish results. Read more…

Announcing BioCoder issue 6

BioCoder 6: iGEM's first Giant Jamboree, an update from the #ScienceHack Hack-a-thon, the Open qPCR project, and more.

Once again, we’re interested in your ideas and in new content, so if you have an article or a proposal for an article, send it in to BioCoder@oreilly.com. We’re very interested in what you’re doing. There are many, many fascinating projects that aren’t getting media attention. We’d like to shine some light on those. If you’re running one of them — or if you know of one, and would like to hear more about it — let us know. We’d also like to hear more about exciting start-ups. Who do you know that’s doing something amazing? And if it’s you, don’t be shy: tell us.

Above all, don’t hesitate to spread the word. BioCoder was meant to be shared. Our goal with BioCoder is to be the nervous system for a large and diverse but poorly connected community. We’re making progress, but we need you to help make the connections.

Design for disruption

A look at the need for design thinking in the IoT, advanced robotics, 3D printing, and synthetic biology.

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from our recent book Designing for Emerging Technologies, a collection of works by several authors, curated and edited by Jon Follett. This excerpt is included in our curated collection of chapters from the O’Reilly Design library. Download a free copy of the Experience Design ebook here.

Let’s look briefly at the disruptive potential of each of these emerging technologies: the IoT, advanced robotics, 3D printing, and synthetic biology — and the need for design thinking in their formations.

The IoT, connected environment, and wearable technology

Download a free copy of the Experience Design ebook here.

Inexpensive sensors providing waves of data can help us gain new insight into the places in which we live, work, and play, as well as the capabilities to influence our surroundings — passively and actively — and have our surroundings influence us. We can imagine the possibilities of a hyper-connected world in which hospitals, factories, roads, airways, offices, retail stores, and public buildings are tied together by a web of data.

In a similar fashion, when we wear these sensors on our bodies, they can become our tools for self-monitoring. Combine this capability with information delivery via Bluetooth or other communication methods and display it via flexible screens, and we have the cornerstones of a wearable technology revolution that is the natural partner and possible inheritor of our current smartphone obsession. If we consider that the systems, software, and even the objects themselves will require design input on multiple levels, we can begin to see the tremendous opportunity resident in the IoT and wearables. Read more…

Biology as the next hardware

Why DNA is on the horizon of the design world.

I’ve spent the last couple of years arguing that the barriers between software and the physical world are falling. The barriers between software and the living world are next.

At our Solid Conference last May, Carl Bass, Autodesk’s CEO, described the coming of generative design. Massive computing power, along with frictionless translation between digital and physical through devices like 3D scanners and CNC machines, will radically change the way we design the world around us. Instead of prototyping five versions of a chair through trial and error, you can use a computer to prototype and test a billion versions in a few hours, then fabricate it immediately. That scenario isn’t far off, Bass suggested, and it arises from a fluid relationship between real and virtual.

Biology is headed down the same path: with tools on both the input and output sides getting easier to use, materials getting easier to make, and plenty of computation in the middle, it’ll become the next way to translate between physical and digital. (Excitement has built to the degree that Solid co-chair Joi Ito suggested we change the name of our conference to “Solid and Squishy.”)

I spoke with Andrew Hessel, a distinguished research scientist in Autodesk’s Bio/Nano/Programmable Matter Group, about the promise of synthetic biology (and why Autodesk is interested in it). Hessel says the next generation of synthetic biology will be brought about by a blend of physical and virtual systems that make experimental iteration faster and processes more reliable. Read more…

The revolution in biology is here, now

Biological products have always seemed far off. BioFabricate showed that they're not.

Installation view of The Living’s Hy-Fi, the winning project of The Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1’s 2014 Young Architects Program. Photograph by Kris Graves.

The products discussed at BioFabricate aren’t what I thought they’d be. I’ve been asked plenty of times (and I’ve asked plenty of times), “what’s the killer product for synthetic biology?” BioFabricate convinced me that that’s the wrong question. We may never have some kind of biological iPod. That isn’t the right way to think.

What I saw, instead, was real products that you might never notice. Bricks made from sand that are held together by microbes designed to excrete the binder. Bricks and packing material made from fungus (mycelium). Plastic excreted by bacteria that consume waste methane from sewage plants. You wouldn’t know, or care, whether your plastic Lego blocks are made from petroleum or from bacteria, but there’s a huge ecological difference. You wouldn’t know, or care, what goes into the bricks used in the new school, but the construction boom in Dubai has made a desert city one of the world’s largest importers of sand. Wind-blown desert sand isn’t useful for industrial brickmaking, but the microbes have no problem making bricks from it. And you may not care whether packing materials are made of styrofoam or fungus, but I despise the bag of packing peanuts sitting in my basement waiting to be recycled. You can throw the fungal packing material into the garden, and it will decompose into fertilizer in a couple of days. Read more…

A programming language for biology

Antha is a high-level, open source language for specifying biological workflows.

Editor’s note: This is part of our investigation into synthetic biology and bioengineering. For more, download the new BioCoder Fall 2014 issue here.

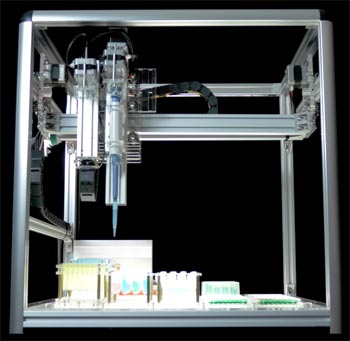

The OT.One liquid handling robot, photo courtesy of OpenTrons.

A programming language for scientific experiments is important for many reasons. Most simply, a scientist in training spends many, many hours of time learning how to do lab work. That sounds impressive, but it really means moving very small amounts of liquid from one place to another. Thousands of times a day, thousands of days in preparation for a career. It’s boring, dull, and necessary work, and something that can be automated. Biologists should spend most of their time thinking about biology, designing experiments, and analyzing results — not handling liquids. Read more…