Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw

Carl Malamud has this funny idea that public domain information ought to be... well, public. He has a history of creating public access databases on the net when the provider of the data has failed to do so or has licensed its data only to a private company that provides it only for pay. His technique is to build a high-profile demonstration project with the intent of getting the actual holder of the public domain information (usually a government agency) to take over the job.

Carl's done this in the past with the SEC's Edgar database, with the Smithsonian, and with Congressional hearings. But now, he's set his eyes on the crown jewels of public data available for profit: the body of Federal case law that is the foundation of multi-billion dollar businesses such as WestLaw.

In a site that just went live tonight, Carl has begun publishing the full text of legal opinions, starting back in 1880, and outlined a process that will eventually lead to a full database of US Case law. Carl writes:

1. The short-term goal is the creation of an unencumbered full-text repository of the Federal Reporter, the Federal Supplement, and the Federal Appendix.

2. The medium-term goal is the creation of an unencumbered full-text repository of all state and federal cases and codes.

This is clearly public data, but as Carl wrote in a letter to West Publishing that accompanies the first data release on his site, asking for clarification about what information West considers proprietary versus public domain:

In looking through the court decisions of a decade ago where West and your commercial competitors fought over the right to re-publish case law, it seems fairly clear that a large part of the publication stream is tightly interwoven into the very substance of the operation of the courts, with West serving as the either contractual or de-facto sole vendor reporting on behalf of the court."

Carl's letter goes on to ask West to release the full text of the Federal Reporter, Federal Supplement, and Federal Appendix. He says:

You have already received rich rewards for the initial publication of these documents, and releasing this data back into the public domain would significantly grow your market and thus be an investment in your future.

Elsewhere in the letter, he writes:

We wish to make this information available to a population that today does not have access to the decisions of our federal and state courts because they are not commercial subscribers to one of the handful of services such as your award-winning Westlaw tools. Codes and cases are the very operating system of our nation of laws, and this system only works if we can all openly read the primary sources. It is crucial that the public domain data be available for anybody to build upon.

Now, it could be that West will eventually go along. Their real proprietary data isn't the text of the case law itself so much as it is in their key number system and accompanying summaries, or "headnotes" as well as their value-added tools for searching and managing the voluminous amount of data. But Carl's project is intended to point out that if they don't, he'll be able to make the data public anyway.

(Note: in the last decade, the Federal courts have begun publishing the data on current opinions, and law professor Tim Wu's AltLaw site provides a full text search engine for those recent cases. But the historical record is much more difficult.)

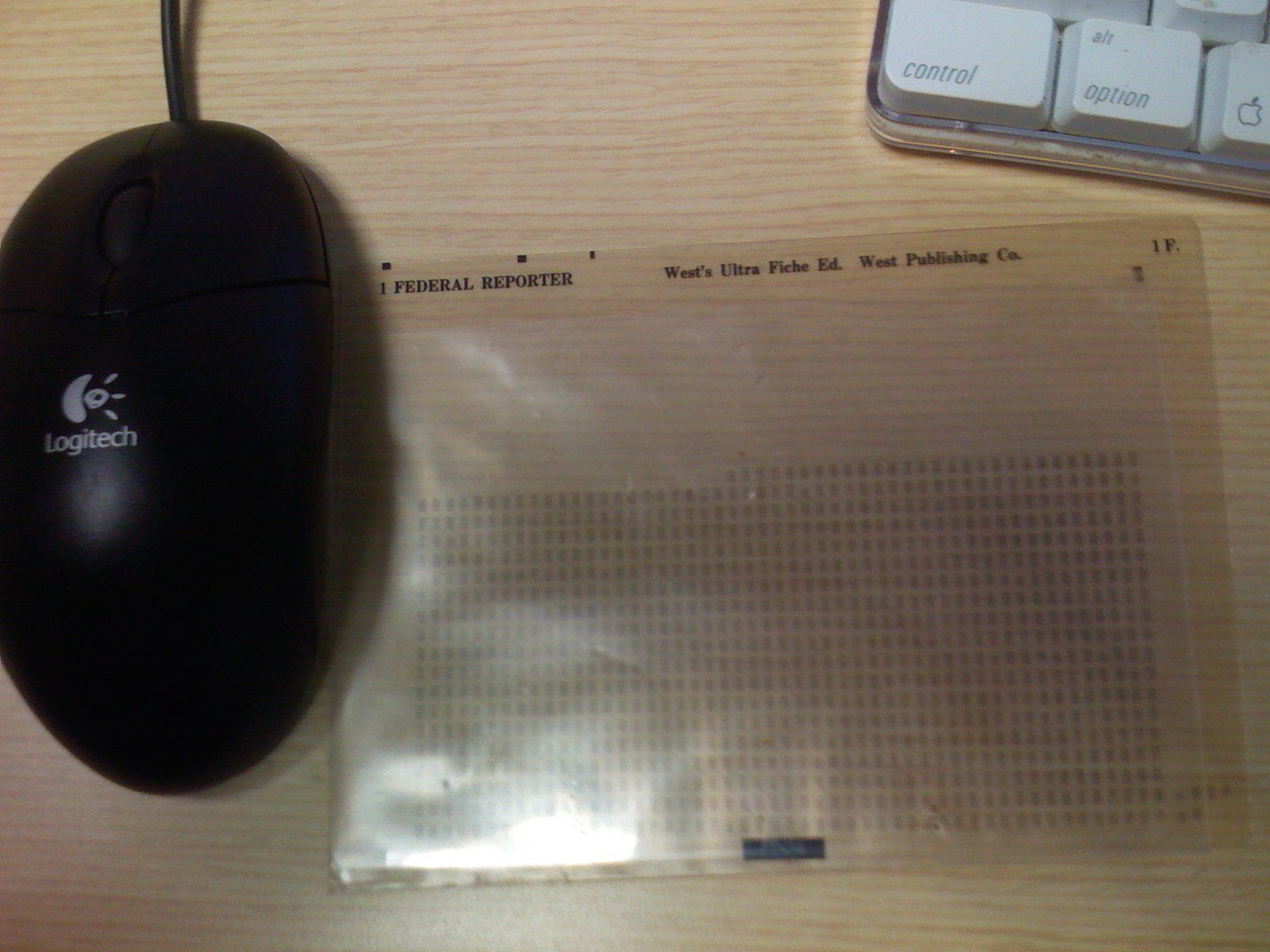

Carl's starting point is the "ultrafiche" version of the Federal Reporter, which West published before the advent of online database versions. An ultrafiche presents up to 1000 pages on a 4 by 6 inch transparency, like the one shown below:

Carl has begun enlarging, processing, and publishing the images, and beginning the process of OCRing them to extract the text. After 87x enlargement, the test images are quite readable. (Click the image below to see at full size):

In private email, Carl wrote:

The SEC database was fairly straightforward, taking a couple of years of hard work. But, getting patents online took 5 years of drawing lines in the sand and sending shots across the bow. Our line in the sand here is all state and federal cases and codes, and I guess our shot across the bow is publishing a 3.6 gbyte tiff file and announcing our intention to systematically walk through the 5 million or so pages of federal case law.

That's a big challenge, but with computing power and storage getting ever cheaper, and with the dedication of volunteers like Carl, it does indeed seem like a possible project. (After all, when Carl pressured the SEC to put its Edgar database online in the early 90's, they said it would take years and millions of dollars. Carl did it in six weeks, and operated the database for two years before persuading the SEC to take it over.)

P.S. John Markoff has covered Carl's escapades for at least as long as I have, so I wasn't surprised to see him at Carl's offices (now on the O'Reilly campus in Sebastopol) last week. His coverage of this story for the New York Times is here.

tags: open source, publishing

| comments: 18

| Sphere It

submit: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

0 TrackBacks

TrackBack URL for this entry: http://blogs.oreilly.com/cgi-bin/mt/mt-t.cgi/5781

Comments: 18

...they're not likely to release a free version of their value-added materials.

Nor should they. But the plain fact is that once the court proceedings are disentangled from the copyrightable material that West owns, others will be free to write their own tools to categorize and access the information. Since what we're talking about is the substance of our laws, it should not be locked up and only available to legal professionals who can afford the (quite expensive) subscription fees.

I'm a Research Scientist for Thomson (parent company of Westlaw) and also an O'Reilly author, but this post only reflects my personal knowledge and views, not those of Thomson (or O'Reilly :-).

First, there are already many places on the net where people can find the raw text of cases or statutes for free. See for example findlaw.com or municode.com or law.cornell.edu. I don't know how encyclopedic such data is, but a first step might be for Carl to find out how much of what he's scanning is already out there.

Also, often the letter of the law isn't very enlightening unless you also know how it's been interpreted by the courts and/or how it might have been amended by legislatures over time. This is the kind of value-added context provided by "premium" companies like West. Or by a lawyer. :-)

Finally, it's important to realize that sometimes rather huge portions of what people see on Westlaw (including the Federal Reporter and the other publications Carl mentions) are actually written by people in West/Thomson's employ, not by the courts. I'm not sure how he's planning to distinguish between the public and copyrighted content from the microfiches he's scanning, but it doesn't seem like an easy task.

It would seem like in this case a good approach would be to assemble a collection of links to what public-domain material is already available out there. Even this, though, has been done by various law schools.

A long time ago, I did some work in this space. It's an interesting question as to whether the page numbers used for citation are intellectual property created by West, when it typesets the page, or the court when it chooses when to stop prattling on. Or it could be that neither is sufficiently sophisticated to be worthy of any protection.

When I was working in the area, I floated an idea of using percentages instead of page numbers. A citation that wanted to point to a line 24.5% of the way through text would use the number 24.5% instead of the page number. It was more precise and, I contended, easy to understand, at least for lawyers who charge 33% as a contingency fee.

This was roundly disliked, perhaps because it was new. But I also felt it was cultural. Non-mathematical folks just didn't think naturally in percentages. (The sub-prime mortgage problem is one corrollary caused by quick talking percentage-thinkers who take advantage of the innumeracy of the general population.)

Wow... this whole thread is a blast from the past; WestLaw was being beat up on just this point at, IIRC, Computers, Freedom & Privacy '95 in San Francisco, over the issue of WestLaw's proprietary claims re page numbering.

This is a blast from the past for me as well - and HyperLaw is still in existence and involved in related technology.

For me HyperLaw was an outstanding success: not only were we able to quash West's claims to copyright of the text of their enhanced judicial opinions and the West claims for copyright of citations, but we were able to demonstrate that you did not have to be a multi-billion dollar empire to publish searchable full-text case law.

Even before Netscape 1 was released in December 1994, we were pumping out on CD-ROM over 10,000 current Federal Appellate and Supreme Court opinions a year - at a time when West was brain-washing the judiciary to believe that it was inconceivable for the courts to publish their opinions themselves in electronic form.

I do suspect West is still at this game of spook the courts - hence the lack of federal district court cases in any public coherent and complete database - these opinions are not on the "free" FindLaw or the "free" LexisOne. Cutting this Gordian Knot (district court opinions) is HyperLaw's current project.

ADS

[Peter Wayner - that is a name from the past for me - I do remember you.]

Free up to date searchable databases of statutes and court decisions would benefit courts, practitioners and the general public by encouraging legal writing. I am a retired lawyer. When I was in practice my firm paid Lexis (West's main competitor) a lot of money for unlimited use of relatively few databases of state and federal law and single searches - at substantial fees, most often $50 each - of other databases. Access to databases of state and federal law is absolutely required in my specialty, federal civil rights litigation. Now that I no longer have access to those databases - I cannot afford them and I am not affiliated with a law school or other entity which can provide access - I find it very difficult to write about the law. A simple article for a legal newspaper becomes a daunting project if your only tools are a library collection of the books published by West and the relatively limited free public resources on disc and on line. The basics are not the problem: Supreme Court decisions, and most of those of the federal appellate courts, are generally available. The difficulty lies in getting lower court decisions and very recent opinions of the appellate courts. Legal writing requires checking the continued viability of each decision cited. As things stand now this is very difficult to do without Lexis or West databases. Carl Malamud's project, by encouraging legal writing, would benefit the legal profession and the public.

As a professional involved in offline (and online) publishing, I am often left with the feeling that the whole reason for the opacity of copyright status is because of special interest.

If interested parties were not trying to tweak the common-sense copyright laws beyond reasonable recognition, they would not be able to create artificial barriers to entry.

I remember my struggle with publishing some of P G Wodehouse's works which are already listed in Gutenberg as being in the public domain.

I agree with the blogger who said that interpretation is the crux of it. Individual cases are pretty much useless unless you can Shepardize them. That will be the real cool freebie when it comes to the internet: free Shepard's.

Thanks to Ken for the nod to our site (www.law.cornell.edu). We've been working in this space since late 1992, believe it or not -- and it's a blast from the past for us, too.

I admire Carl's ambition in taking on the "back file". Federal Court data is now going online as a matter of course (with a very few exceptions, soon to expire if they haven't already)under the e-Government Act. There's plenty of room for improvement in the way that courts are doing that publishing. My colleague Peter Martin points out the need for more and better use of vendor- and media-neutral citation (www.aallnet.org/products/pub_llj_v99n02/2007-19.pdf). I myself would like to see work done on interoperability standards for metadata in particular -- I have in mind something similar to OAI-PMH for courts, and eventually we'll build it, sooner if we can find funding.

And there is a scad of work to be done in educating reporters of decisions about Web-publishing practices that aid discovery (in the Google sense, not the legal sense) and access on the Web.

Of course as another poster points out a simple resource catalog would be useful, though there are some noble attempts out there already -- ours, WorldLII, numerous smaller catalogs assembled by law libraries, etc.

Two final (maybe contrarian) points: caselaw and copyright aren't the most important issues. The majority of people wanting legal information aren't doing formal legal research, but rather undertaking a kind of risk-management activity similar to what they might do with a site like WebMD. (And for the lawyers out there tempted to start griping about unauthorized-practice issues, the similarities to WebMD run deeper : these folks almost never self-prescribe, and if they do, the effects are probably both drastic and Darwinian, so there's really nothing to fear). For audience like that, judicial opinions are (most of the time) a secondary interpretive layer that surrounds statutes and regulations. What they want is legislation, regulations, and material that interprets those things. So intellectual access is really the barrier in the long run. Semantic-Web notions would be great to apply here, but frankly better interoperation at the simple level of discoverability and linkage to referenced materials would go a long way beyond what most sites have now.

Commenter Ken Williams neglects to mention that findlaw.com is owned by Thomson. The good news for Malamud is that this makes findlaw a good place to see what Thomson considers to be public domain.

Regarding what Rod Kovel said:

Shepards is a LexisNexis product, and WestLaw has their equivalent, and as "cool freebies" go, don't hold your breath waiting for this one. This is one of the most basic examples of the value they add to the content, at no small cost, and one of the things that makes these services expensive.

To reproduce it, not only would you have to implement links from each case to every case it references, you would have to add metadata about the nature of the reference to each link (affirmed, overruled, etc.). If not an actual attorney, it takes someone with serious legal training to do that. This is also the classic example of where Tim Berners-Lee's acceptance of broken links works on the public internet, but where certain audiences can't accept broken links: picture a lawyer who argues in court that a judge should rule in favor of his plaintiff because another judge ruled in favor of the plaintiff in a very similar case, and that the case was never overruled. How sure is he that it was never overruled? An attorney who trusts that regexes written and run by volunteer labor found absolutely every link to the cited case from subsequent cases, and that complete, correct metadata was added to those links, might be in for a surprise. This really is a case of getting what you paid for.

See http://www.oreillynet.com/xml/blog/2003/05/a_nineteenthcentury_linking_ap.html for more on Shepards, where it came from, and what it does.

Tom Bruce has made a good point concerning meta-data:

"[Bruce:] I myself would like to see work done on interoperability standards for metadata in particular -- I have in mind something similar to OAI-PMH for courts, and eventually we'll build it, sooner if we can find funding."

Metadata describing the opinion document is the key, especially for base level data: court, decision date, judge, parties etc. There is/was a legal XML group http://www.legalxml.org/: but there is nothing on this web site since 2003. The big sponsors of that were Reed Elsevier (Lexis) and Thomson (West). In a way, LegalXML was overkill, for it was attempting to provide XML specifications for everything from pleadings, orders, briefs, discovery documents to court opinions. The US Courts Pacer/EDF system avoided the whole XML issue for the text by having documents be filed as Acrobat PDF files, and that is how US Courts now "publish" court opinions - but, there is no metadata at all.

In 1995, HyperLaw proposed the creation of a "Legal Text Markup Language" (LTML) with a special focus to be on citation information but, there was not enough enthusiasm at the time and not a lot of people were into data tagging at that time.

Interestingly, SEC Edgar data has had its own XML like markup language for over a decade - I think Carl will find the absence of this XML like data just one difference betweeen court opinions and SEC Edgar Data. Another difference: the SEC is the "publisher" of 100% of the Edgar data - there are a dizzing number of court sytems and many with independent minded judges (some who cannot be bothered with identifying which of their order qualfify as judicial opinions." There is one more difference. This third difference is that back when the SEC database was "freed" (Jamie Love of the Taxpayers Assets Project and Citation Fights was involved in the SEC Edgar issue as well), there was in fact a government owned, digital, organized, and coherent database on tapes and hard drives with all of the data, nicely tagged and marked and maintained by the government or contractors under contract to do so.

In the meantime, me thinks the backfile of Federal Reporters is already being scanned by Google as part of Google Books (which the NYT reporter Markoff left out of his article, although he was aware of this fact because we discussed it.) I have found on Google Books numerous volumes of the Federal Reporter that have been scanned. What is missing from Google is any meaningful metadata. For some reason, for older out of copyright Federal Reporter, Google is not permitting download of the complete pdf. Interestingly, Google is scanning recent Federal Reporters as well - including the vaunted West copyrighted headnotes.

Other commenters have pointed out that there are many many court opinions on the Internet now. Largely missing from almost all of the tens of thousands of judicial opinions now searchable on the Internet is any useful metadata to aid on identifying, searching and retrieving the opinions.

So, the solution is some standard type of XML metadata for document description and then the exposure of the files to indexing and search on the Internet. Some court opinions sites expose their opinion pdf files, but most do not.

Altlwaw.org has been collecting more recent Court of Appeals opinions; I am not aware of any other site that has exposed versions of all of these opinions: example: http://www.altlaw.org/v1/cases/17886. Rather than expend too much energy and money providing their own search engine etc., their best primary contribution would be to tag (including a tag to the West citation) and provide this metadata in the pdf files using a thoughtful XML/tagging specification that would work for more than the narrow subset of courts (13).

Of course, tagging is a lot of work - and thousands of new federal cases arrive every week. Lexis has a separate database for federal appeals cases - the first case for this year is 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 1. On August 23, 2007, the citation was up to 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 20200 - so the volunteer taggers are going to have 40,000 to 50,000 appeals cases a year to tag, and that is just for the 13 appeals courts.

There are about 186 federal district and bankruptcy courts. Just on the 2007 Lexis US District court database, there are over 62,000 opinions (or orders) as of August 22, 2007.

There is a lot of junk in these opinions (like the one page order at 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 62000), but somehow, one has to separate the useful from the junk.

Alan Sugarman - HyperLaw.

West's "value added" materials really don't add that much value. In fact, they often confuse legal issues. The real value in the Westlaw database (and Lexis) is the monopoly on legal information. Publishing the cases on the Internet will do for lawyers what WebMD did for doctors, both good and bad.

Daniel is right about the utility of West's headnotes. The first thing legal writing professors tell you is not to trust the headnotes too much. I have been told, and can believe, that the headnotes are written by scores of low paid southeast asians without legal degrees. I'd much rather place my faith in the several best FOSS scripts than on tired and guesstimating humans, no matter how well trained. Think of how well Netflix does with movie recommendations, and imagine humans trying to perform the same task. The true "value" of West and Lexis is that they monopolize the public domain. Let's take back our laws!

There are choices other than the big boys vs. public databases. Loislaw.com is becoming one of the leading alternatives.

It generally has the same raw cases for all U.S. jurisdictions, state and federal, going back at least fifty or sixty years, and costs a third or less per month of what West charges. It now also offers a free version to law students.

The search and citation tools in Loislaw may not be as powerful as Westlaw, but it looks like a good resource for smaller law libraries and solo lawyers looking for affordable resources. I can see using Loislaw for basic research and then paying by the page for a final check via Westlaw - or paying in paper time to Shepardize at a local law library.

Then again, I'm just a 1L, not even an infant lawyer yet. :)

A big part of the problem, and it's a problem that West and Lexis make their livings trying to deal with, is the common law system itself. In particular the federal republic we have makes common law even worse than it otherwise might be. Law based on judicial precedent, where no-one really knows what the law is and a lay person can't find out because the statutes are useless, is a bad idea. The common law is rooted in a society with a mostly-inactive legislature, and so the judges had to invent laws where there were none. But now we have the worst of both worlds - an active legislature churning out unreadable statute and a judiciary churning out unknowable decisions.

New free systems are long overdue, but the problem isn't the database - it's the data set.

Post A Comment:

STAY CONNECTED

RECENT COMMENTS

- Adam Birnbaum on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: A big part of the probl...

- Brad Taplin on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: There are choices other...

- Jonathan on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: Daniel is right about t...

- Daniel on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: West's "value added" ma...

- Alan D. Sugarman on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: Tom Bruce has made a go...

- Bob DuCharme on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: Commenter Ken Williams ...

- Thomas R. Bruce on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: Thanks to Ken for the n...

- Rod Kovel on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: I agree with the blogge...

- Ajeet Khurana on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: As a professional invol...

- William Barnes on Carl Malamud Takes on WestLaw: Free up to date searcha...

Jorge [08.20.07 07:18 AM]

You gloss over the most important details: Westlaw's value rests entirely on the value-added materials, such as the KeyCites and Key Numbers.

The text of federal cases are publicly available in libraries (law school libraries and larger municipal libraries).

Westlaw may take over managing a text-only database, but they're not likely to release a free version of their value-added materials.