A while ago, I wrote a short post on the meaninglessness of frictionless sharing. Since then, I’ve had a few additional thoughts on what frictionless sharing is trying to accomplish (aside from pure and simple marketing), and what we should be trying to build.

A while ago, I wrote a short post on the meaninglessness of frictionless sharing. Since then, I’ve had a few additional thoughts on what frictionless sharing is trying to accomplish (aside from pure and simple marketing), and what we should be trying to build.

The article about Target targeting pregnant women with advertisements caught my attention, not particularly because of Target’s practice, but because it gives us a useful way of looking at the history of privacy. What Target did isn’t at all surprising. Target’s data systems noticed that some women were suddenly buying extra large handbags (for holding diapers), over-the-counter medicines that could be used to fight morning sickness, and skin creams to hide stretch marks. The store concluded that these women were probably pregnant and targeted them with ads featuring products for pregnant women. (If you believe the rather self-serving story about how one girl’s father called the store furious about what these ads were implying, then called back the next day to apologize, you’re less skeptical than I am.)

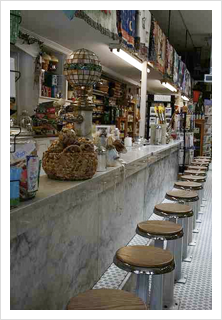

It’s not surprising that this makes the news, but I asked myself what’s really new here. And my answer is, “not much.” Think back to the first half of the 20th century. A girl walks into the local pharmacy and buys bicarb for an upset stomach. The pharmacist notes that this girl has never bought anything like this before and also notes that she’s looking a bit thicker. He has also seen the girl at the lunch counter and knows she has an iron stomach. He puts two and two together, makes a mental note, and knows what to recommend the next time she’s in. And soon after the pharmacist knew it, you can bet that everyone knew it; people never needed the Internet to form networks. I would gladly bet that this story played itself out thousands of times.

What’s interesting is what happened in the years that intervened between the ’50s and the present. The small town culture (which may never have really existed) in which everyone knew everything about everyone disappeared as we moved into suburbs, where nobody knew anything about anyone. And that’s really where our notions of “privacy” arose. The local pharmacies started disappearing, to be replaced by big chains like CVS and Walgreens. As Douden’s and Jolly’s disappeared from local culture, so did the local pharmacist who knew and remembered who you were and what you bought, and who was able to put two and two together without the help of a Hadoop cluster. Around 60-70 years ago, we didn’t really have any privacy; Scott McNealy’s infamous statement that “you have zero privacy anyway … get over it” would have been meaningless. We grew attached to our privacy in the intervening half-century, as the demands of industry created population concentrations that broke the bonds (wanted or not) attaching us to our local neighbors. In the past, we “heard it through the grapevine,” but by the time the Internet was invented, that grapevine had been uprooted.

I am the last person to claim that the ’50s were some sort of paradise when all was right in America and the world. In many ways, the ’50s were a sick and deformed conformist culture. But the ’80s were no party either. I was in grad school at the time, and all the non-students I knew (mostly engineers in Silicon Valley) were bemoaning the lack of “community.” They lived in anonymous apartment complexes in insipid suburbs; they were tired of the people they worked with; there was no good way to make friends, no good way to be social. The big social story of the ’80s and ’90s was the decline of “social” and the continued rise of suburban cocooning in detached houses. In this environment, the rise of Facebook and Foursquare (and MySpace, and Friendster, and Orkut and others) was inevitable. Given the boredom of mid-’80s apartment complex existence, software developers did what came naturally and invented a software solution.

We have to look at automated sharing of the music we listen to, the books we read, and the restaurants we visit in light of that arc. As anyone who is interested in books or records knows, the first thing you used to do when you visited someone’s house was look at their bookshelves or their stack of records (or CDs). You might lend me a book or a record that I was interested in, moving a step up the ladder from acquaintance to intimacy. That still works, but at O’Reilly’s recent TOC conference, it was clear that even publishers understand that the age of print is coming to the end. SOPA and PIPA have more to do with the entertainment industry realizing that CDs and DVDs have come to an end than they have to do with so-called piracy. Print books will survive as fetishized items, as will vinyl LPs: expensive coffee-table books for display, a few high-priced show editions, but nothing as interesting as what you’d find on my bookcase. That inevitable shift signals a profound change for the social nature of reading and listening. While looking through someone’s bookshelves is fine, it’s not socially acceptable to look through their iPods and Kindles.

In this context, it’s surely correct to put a kinder interpretation on automated “frictionless sharing” of your songs and book purchases on Facebook. Yes, if someone is giving you a service for free, you’re not the customer — you’re the product. It’s reasonable to be unhappy that your likes and dislikes are being bought and sold like pork bellies on the Chicago Merc. But there is an oddly pathetic humanity behind automated sharing: It’s a clumsy and intrusive attempt to solve a very real human problem with technology. After all, that’s what technologists do. Asking a software developer not to write software when faced with an obvious problem is like asking a fish not to swim. As I said, that’s how we got Facebook in the first place.

Automated, frictionless sharing is certainly not a solution. As I’ve often observed, human problems are almost always solved by human solutions, very rarely by technical solutions. We have to ask ourselves what the real solution is, given that we’ve negotiated an arc from immersion in a social community (with all that entails) to helplessly private insularity to immersion in a virtual world that lacks privacy, but that also lacks human contact. It may be that dating sites are so consistently popular because they are the only online services that require human contact to work.

So how do we think about a solution? Privacy, data, and our social nature are inevitably entangled — always have been and always will be. How do we build satisfying human connections back into our lives without the superficiality and invasiveness of automated sharing? We’ve given up privacy without gaining the benefits of increased openness, which are tied up with social interaction. Back in the ’80s, I couldn’t look at your bookshelves unless you invited me to your party. That’s real friction. Now, I can see your data, but even if you send me a personal email with your playlist, there’s no party. And that’s the challenge: bring real human connection back to our sanitized technology. The world isn’t just about Facebook and Twitter, or even Google+. It’s about making connections and having real parties with real food and real people. Gregory Brown, founder of Mendicant University, and one of the authors I’ve worked with, is having a party this Spring for “people with interesting ideas.” I sure hope I’m invited because that’s the only way out.

Photo: Soda fountain by LandVike, on Flickr

Related: