Python tuples have a surprising trait: they are immutable, but their values may change. This may happen when a tuple holds a reference to any mutable object, such as a list. If you need to explain this to a colleague who is new to Python, a good first step is to debunk the common notion that variables are like boxes where you store data.

In 1997 I took a summer course about Java at MIT. The professor, Lynn Andrea Stein — an award-winning computer science educator — made the point that the usual “variables as boxes” metaphor actually hinders the understanding of reference variables in OO languages. Python variables are like reference variables in Java, so it’s better to think of them as labels attached to objects.

Here is an example inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee are twins. From the book: “Alice knew which was which in a moment, because one of them had ‘DUM’ embroidered on his collar, and the other ‘DEE’.”

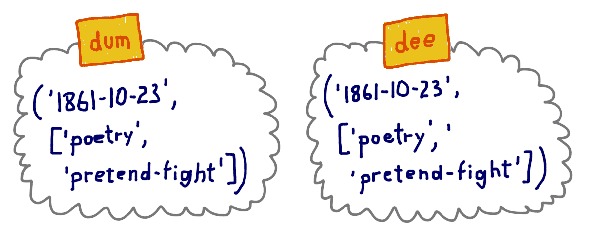

We’ll represent them as tuples with the date of birth and a list of their skills:

>>> dum = ('1861-10-23', ['poetry', 'pretend-fight'])

>>> dee = ('1861-10-23', ['poetry', 'pretend-fight'])

>>> dum == dee

True

>>> dum is dee

False

>>> id(dum), id(dee)

(4313018120, 4312991048)

It’s clear that dum and dee refer to objects that are equal, but not to the same object. They have distinct identities.

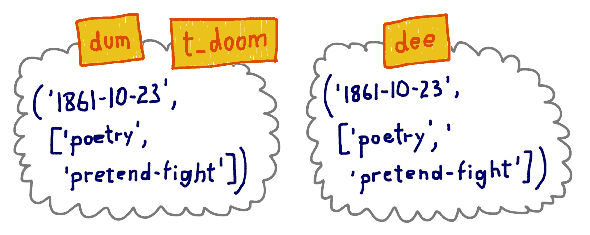

Now, after the events witnessed by Alice, Tweedledum decided to become a rapper, adopting the stage name T-Doom. This is how we can express this in Python:

>>> t_doom = dum

>>> t_doom

('1861-10-23', ['poetry', 'pretend-fight'])

>>> t_doom == dum

True

>>> t_doom is dum

True

So, t_doom and dum are equal — but Alice might complain that it’s foolish to say that, because t_doom and dum refer to the same person: t_doom is dum.

The names t_doom and dum are aliases. I like that the official Python docs often refer to variables as “names”. Variables are names we give to objects. Alternate names are aliases. That helps freeing our mind from the idea that variables are like boxes. Anyone who thinks of variables as boxes can’t make sense of what comes next.

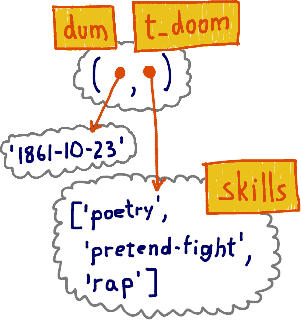

After much practice, T-Doom is now a skilled rapper. In code, this is what happened:

>>> skills = t_doom[1]

>>> skills.append('rap')

>>> t_doom

('1861-10-23', ['poetry', 'pretend-fight', 'rap'])

>>> dum

('1861-10-23', ['poetry', 'pretend-fight', 'rap'])

T-Doom acquired the 'rap' skill, and so did Tweedledum — of course, they are one and the same. If t_doom was a box containing a str and a list, how could you explain that appending to the list in t_doom also changes the list in the dum box? However, it makes perfect sense if you see variables as labels.

The label analogy is much better because aliasing is explained simply as an object with two or more labels. In the example, t_doom[1] and skills are two names given to the same list object, just as dum and t_doom are two names given to the same tuple object.

Below is an alternative depiction of the objects that represent Tweedledum. This figure emphasizes that a tuple holds references to objects.

What is immutable is the physical content of a tuple, consisting of the object references only. The value of the list referenced by dum[1] changed, but the referenced object id is still the same. A tuple has no way of preventing changes to the values of its items, which are independent objects and may be reached through references outside of the tuple, like the skills name we used earlier. Lists and other mutable objects inside tuples may change, but their ids will always be the same.

This highlights the difference between the concepts of identity and value, described in Python Language Reference Data model chapter:

Every object has an identity, a type and a value. An object’s identity never changes once it has been created; you may think of it as the object’s address in memory. The ‘is’ operator compares the identity of two objects; the id() function returns an integer representing its identity.

After dum became a rapper, the twin brothers are no longer equal:

>>> dum == dee False

We have two tuples that were created equal, but now they are different.

The other built-in immutable collection type in Python, frozenset, does not suffer from the problem of being immutable yet potentially changing in value. That’s because a frozenset (or a plain set, for that matter) may only hold references to hashable objects, and the value of hashable objects may naver change, by definition.

Tuples are commonly used as dict keys, and those must be hashable — just as set elements. So, are tuples hashable or not? The right answer is: some tuples are hashable. The value of a tuple holding a mutable object may change, and such a tuple is not hashable. To be used as a dict key or set element, the tuple must be made only of hashable objects. Our tuples named dum and dee are unhashable because each contains a list reference, and lists are unhashable.

Now let’s focus on the assignment statements at the heart of this whole exercise.

Assignment in Python never copies values. It only copies references. So when I wrote skills = t_doom[1] I did not copy the list at t_doom[1], I only copied a reference to it, which I then used to change the list by doing skills.append('rap').

Back at MIT, Prof. Stein spoke about assignment in a very deliberate way. For example, when talking about a seesaw object in a simulation, she would say: “Variable s is assigned to the seesaw”, but never “The seesaw is assigned to variable s“. With reference variables it makes much more sense to say that the variable is assigned to an object, and not the other way around. After all, the object is created before the assignment.

In an assignment such as y = x * 10, the right-hand side is evaluated first. This creates a new object or retrieves an existing one. Only after the object is constructed or retrieved, the name is assigned to it.

Here is proof in code. First we create a Gizmo class, and an instance of it:

>>> class Gizmo:

... def __init__(self):

... print('Gizmo id: %d' % id(self))

...

>>> x = Gizmo()

Gizmo id: 4328764080

Note that the __init__ method displays the id of the object just created. This will be important in the next demonstration.

Now let’s instantiate another Gizmo and immediately try to perform an operation with it before binding a name to the result:

>>> y = Gizmo() * 10 Gizmo id: 4328764360 Traceback (most recent call last): ... TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for *: 'Gizmo' and 'int' >>> 'y' in globals() False

This snippet shows that the new object was instantiated (its id was 4328764360) but before the y name could be created, a TypeError aborted the assignment. The 'y' in globals() check proves there is no y global name.

To wrap up: always read the right-hand side of an assignment first. That’s where the object is created or retrieved. After that, the name on the left is bound to the object, like a label stuck to it. Just forget about the boxes.

As for tuples, make sure they only hold references to immutable objects before trying to use them as dictionary keys or put them in sets.

This post was based on chapter 8 of my Fluent Python book. That chapter, titled Object references, mutability, and recycling also covers the semantics of function parameter passing, best practices for mutable parameter handling, shallow copies and deep copies, and the concept of weak references — among other topics. The book focuses on Python 3 but most of its content also applies to Python 2.7, like everything in this post.

Public domain illustration from Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There.”