About 10 years ago, “geo” and “local” were two very distinct product verticals in most Internet companies. This was in part because what we now think of as local arose out of a Yellow Pages market, while the mapping use case arose from more enterprise, maps-and-navigation origins.

At the time, most Internet businesses were keen to perpetuate extant geo-local user experiences, rather than seeing them as crude, if profitable, interim steps to something better. Nowhere was this more evident than at my former employer, Yahoo: as late as 2006, investment cases were still being pitched for either maps or local; the bulk of Yahoo’s geo engineering team resided in an entirely different country; and the mobile group had its own building with few, if any, connections to the rest of the company.

Today, entrepreneurs and execs know that local, geo, and mobile are not distinct product groups and technology stacks, but rather essential components of a unified toolset that better connects people with the world around them.

Nothing better reflects the diversity of this geo toolkit than the products on display at the recent Where 2.0 conference. The three-day event embraced the full spectrum of all things spatial: coding, licensing, marketing, daily deals, 3D visualization, and a bit of mapping thrown in for the traditionalists in the audience.

In this context I gave a short presentation on “Big Data, Big Local.” I’ve embedded the slides below. Although I anticipate receiving an award for including Borat, Homer Simpson, Bender, Winston Churchill, porn shops, kittens, surfing, and unicorns coherently in a single presentation on geo — the deck does not stand well on its own. Go figure.

I wanted therefore to provide a brief overview here, and perhaps tackle it more fully in subsequent posts. This is not intended to be a detailed argument, simply an accompanying narrative to the deck.

The general tenor of the discussion focuses upon how we have traditionally employed coordinates as the final word in how we position things and people in the physical world. The problem with this approach is that a coordinate pair lacks context — they are regular and orderly, which is great for machines, but are entirely ambiguous when used to represent more conceptual places like states, cities, stores and neighborhoods. That’s not so good for people. In fact, a single coordinate pair can be used to represent all these places, and their different associations, concurrently.

Social location has moved us toward a new form of positioning: by business or points of interest (POI). These geo-referenced entities exist across the world in an irregular and poorly typed graph, but they are rich with context. People exist and events happen at places, not coordinates — social location applications “snap” us to these nodes, and their context becomes ours.

We are stretching the traditional use of business listings beyond their limits. Looking back, however, you can see how they’ve been continuously extended to fit new models of bringing consumers and businesses closer together. You’ll soon see listings data act as hooks in the mobile payments space, and they will become increasingly pivotal in creating rich topological graphs among people, brands, and physical places.

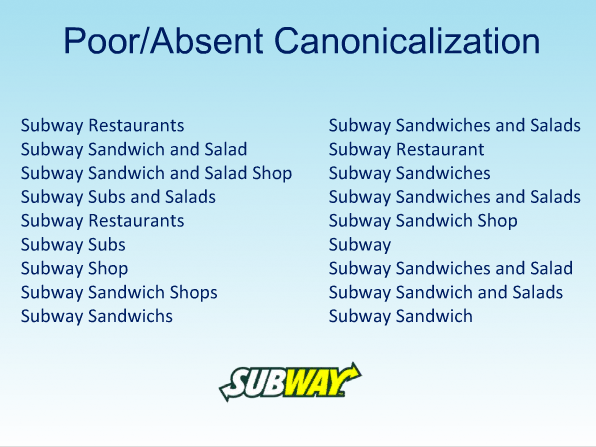

We can do great things with business listings and POI as geo-commercial beacons, but they come with their own problems, two of which I cover in the deck. The first is a more pedestrian example of name canonicalization: stores in the same retail / restaurant chain are represented today in too many forms. The evidence presented by variants on “Subway Sandwiches” in slide 12 (below) would suggest that current data providers expend comparatively little effort normalizing this content. The problem may exist because this information is currently intended to serve an extant, limited use case — make the name discoverable using free text search and present to users — rather than drive new, data-driven markets.

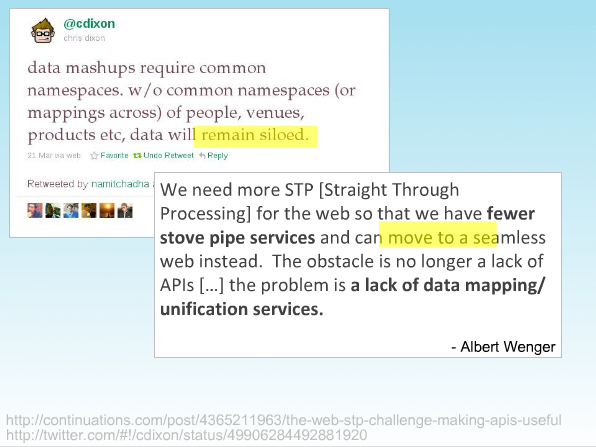

The second, more important issue is that we are faced on the Internet with a multitude of electronic incarnations of one physical entity. While intended to enhance discoverability across properties, the current situation effects a near-complete inability to understand how users engage electronically with a physical place outside a single caisson such as Facebook, Twitter, or Yelp. This need is increasingly important, because URLs are now often employed as surrogates for a place — they can be resolved to machine-readable attributes and in fact act exactly like nodes in a graph of linked data.

This is a problem that requires solving, and we are tackling it at Factual. I include some topical commentaries from Chris Dixon and Albert Wenger as artillery support in slide 18:

So the problem is that we are collectively going to need this normalization, very soon. I conclude noting that Factual’s duty does not end with the creation of tab-delineated files. Instead, we are looking to create data-centric platforms that instill order on an increasingly chaotic Internet, and ensure that the result is meeting the future business needs of our contemporaries in the local space.

Related: