Files are an outdated concept. As we go about our daily lives, we don’t open up a file for each of our friends or create folders full of detailed records about our shopping trips. Create, watch, socialize, share, and plan — these are the new verbs of the Internet age — not open, save, close and trash.

Files are an outdated concept. As we go about our daily lives, we don’t open up a file for each of our friends or create folders full of detailed records about our shopping trips. Create, watch, socialize, share, and plan — these are the new verbs of the Internet age — not open, save, close and trash.

Clinging to outdated concepts stifles innovation. Consider the QWERTY keyboard. It was designed 133 years ago to slow down typists who were causing typewriter hammers to jam. The last typewriter factory in the world closed last month, and yet even the shiny new iPad 2 still uses the same layout.

Creative alternatives like Dvorak and more recently Swype still struggle to compete with this deeply ingrained idea of how a keyboard should look.

Today we use computers for everything from booking travel to editing snapshots, and we accumulate many thousands of files. As a result, we’ve become digital librarians, devising naming schemes and folder systems just to cope with the mountains of digital “stuff” in our lives.

The file folder metaphor makes no sense in today’s world. Gone are the smoky 1970s offices where secretaries bustled around fetching armfuls of paperwork for their bosses, archiving cardboard files in dusty cabinets. Our lives have gone digital and our data zips around the world in seconds as we buy goods online or chat with distant relatives.

A file is a snapshot of a moment in time. If I email you a document, I’m freezing it and making an identical copy. If either of us wants to change it, we have to keep our two separate versions in sync.

So it’s no wonder that as we try and force this dated way of thinking onto today’s digital landscape, we are virtually guaranteed the pains of lost data, version conflicts and failed uploads.

It’s time for a new way to store data – a new mental

model that reflects the way we use computers today.

OSCON Data 2011, being held July 25-27 in Portland, Ore., is a gathering for developers who are hands-on, doing the systems work and evolving architectures and tools to manage data. (This event is co-located with OSCON.)

OSCON Data 2011, being held July 25-27 in Portland, Ore., is a gathering for developers who are hands-on, doing the systems work and evolving architectures and tools to manage data. (This event is co-located with OSCON.)

Flogging a dead horse

Microsoft, Apple and Linux have all failed to provide ways to work with our data in an intuitive way. Many new products have emerged to try and ease our pain, such as Dropbox and Infovark, but they’re limited by the tired model of files and folders.

The emergence of Web 2.0 offered new hope, with much brouhaha over folksonomies. The idea

was to harness “people power” by getting us to tag pictures or websites with meaningful labels, removing the need for folders. But Flickr and Delicious, poster boys of the tagging revolution, have fallen from favor and as the tools have stagnated and enthusiasm for tagging has dwindled.

Clearly, human knowledge is needed for computers to make

sense of our data – but relying on human effort to digitize that knowledge by labeling files or entering data can only take us so far. Even Wikipedia has vast gaps in its coverage.

Instead, we need computers to interpret and organize data

for us automatically. This means they’ll store not only our data, but also

information about that data and what it means – metadata. We need them to really understand our digital information as something more than a set of text documents and binary streams. Only then will we be freed from our filing frustrations.

I am not a machine, don’t make me think like one

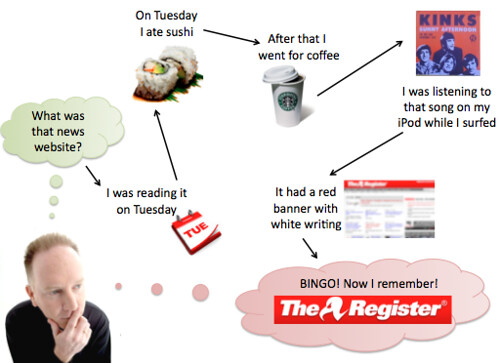

In all our efforts to interact with computers, we’re forced to think like a machine: What device should I access? What format is that file? What application should I launch to read it? But that’s not how the brain works. We form associations between related things, and that’s how we access our memories:

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could navigate digital data in this way? Isn’t it about time that computers learned to express the world in our terms, not theirs?

It might seem like a far-off dream, but it’s achievable. To do this, computers will need to know what our data relates to. They can learn this by capturing information automatically and using it to annotate our data at the point it is first stored — saving us from tedious data entry and filing later.

For example, camera manufacturers have realized that adding GPS to cameras provides valuable metadata for each photograph. Back at your PC, your geo-tagged images will

be automatically grouped by time and location with zero effort.

Our digital lives are full of signals and sensors that can be similarly harnessed:

- ReQall

uses your calendar and to-do list activity to help deliver information at the

right time. - RescueTime tracks the websites and programs you use to understand your working habits.

- Lifelogging projects like MyLifeBits go further still,

recording audio and video of your life to provide a permanent record. - A research project at Ryerson University demonstrates the idea of context-aware computing — combining live, local data and user information to deliver highly relevant, customized content.

Semantics: Teaching computers to understand human language

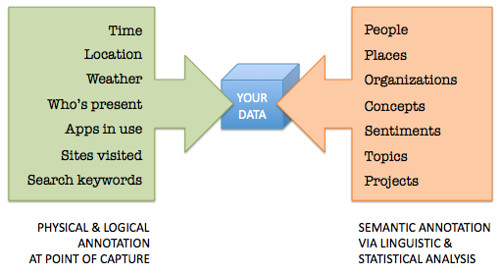

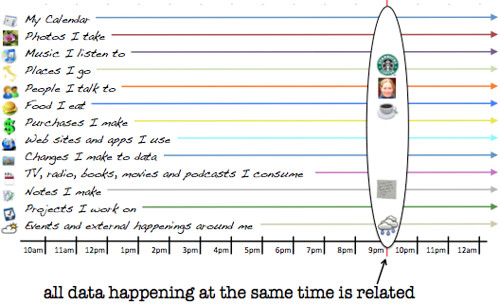

As this diagram shows, hardware and software sensors can

only tell half the story. Where computers stand to learn the most is by analyzing

the meanings behind the 1s and 0s. Once computers understand our language, our documents and correspondence are no longer just isolated files. They become source material, full of facts and ready to be harvested.

This is the science of semantics — programs that can extract meaning from the written word.

Here’s some of what we can do with semantic technology

today:

- Extract people, places, concepts and even sentiments from

text, with software like OpenCalais

and OpenText Semantic

Navigation. - Summarize documents to a desired length, with software

like OpenCyc and Copernic Summarizer.

Today, most semantic research is done by enterprises that can

afford to spend time and money on enterprise content management (ECM) and content analytics systems to make

sense of their vast digital troves. But soon consumers will reap the benefits

of semantic technology too, as these applications show:

- While surfing the web, we can chat and interact around particular movies, books or activities using the browser plug-in GetGlue, which scans the text in the web pages you visit to identify recognized social objects.

- We will soon have our own intelligent agents, the first of which is Siri, an iPhone app that can book movie tickets or make restaurant reservations without us having to fill in laborious online forms.

This ability for computers to understand our content is critical as we move toward file-less computing. A new era of information-based applications is beginning, but its success requires a world where information isn’t fragmented across different files.

Time for a new view of data

Let’s use your summer vacation as an example: All the digital information relating to your vacation is scattered across hundreds of files, emails and transactions, often locked into different applications, services and formats.

No matter how many fancy applications you have for “seamlessly syncing” of all these files, any talk of interoperability is meaningless until you have a basic fabric for viewing and interacting with your data at a higher level.

If not files, then what? The answer is surprisingly simple.

What is the one thing all your data has in common?

Time.

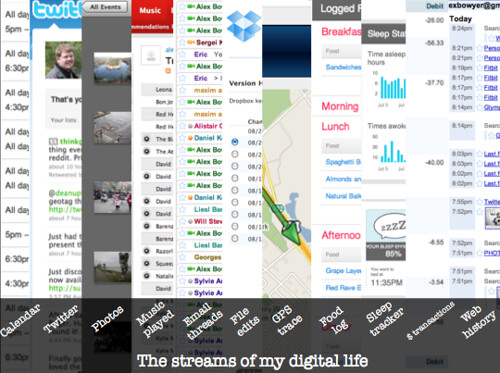

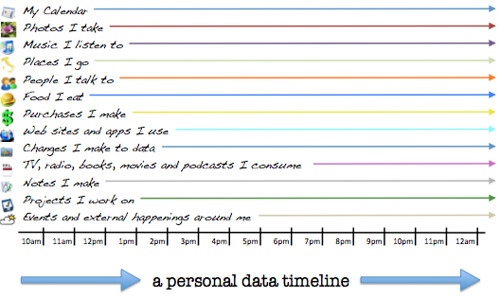

Almost all data can be thought of as a stream, changing over time:

Already we generate vast streams of data as we go about our lives: credit card purchases, web history, photographs, file edits. We never get to see them on screen like that though. Combining these streams into a

single timeline — a personal life stream — brings everything together in a way that makes sense:

Asking the computer “Show me everything I was doing at 3 p.m. yesterday.” or “Where

are Thursday’s figures?” is something we can’t easily do today. Products such as AllOfMe are beginning to experiment in this space.

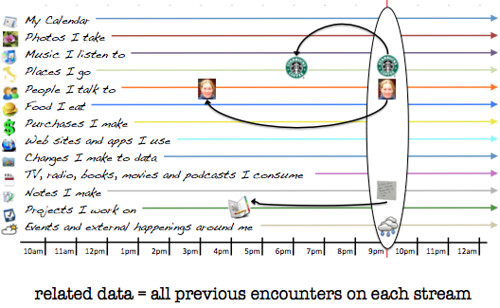

We can go further — time itself can be used to help associate things. For example: Since I can only be in one place at one time, everything that happens there and then must be related:

The computer can easily help me access the most relevant information — it just needs to track back along the streams to the last time I was at a certain place or with a specific person:

The world — our lives — is interconnected, and data needs to be the same.

This timeline-based view of data is useful, but it becomes even more powerful when combined with the annotations and semantic metadata gathered earlier. With this much cross-linking between data, our information can now be associated with everything it relates to, automatically.

Finally, we can do away with files because we have a system that

works like the brain does – giving us another new power — to

traverse effortlessly from one related concept or entity to another until we

reach the desired information:

In a system like this we navigate based on what the data means to us – not which file it is located in.

There will be technical challenges in maintaining data that resides on different devices and is held by different service providers, but cloud computing industry giants like Amazon and Google have already solved much more difficult problems.

A world without files

In the world of linked data and semantically indexed information, saving or losing data is not something we’ll have to worry about. The stream is saved. Think about it: You’d never have to organize your emails or project plans because everything would be there, as connected as the thoughts in your head. Collaborating and sharing would simply mean giving other people access to read from or contribute to part of your stream.

We already see a glimpse of this world when we look at Facebook. It’s no wonder that it’s so successful; it lets us deal with people, events, messages and photos — the real fabric of our everyday lives — not artificial constructs like files, folders and programs

Files are a relic of a bygone age. Often, we hang onto ideas long past their due date because it’s what we’ve always done. But if we’re willing to let go of the past, a fascinating world of true human-computer interaction

and easy-to-find information awaits.

Moving beyond files to associative and stream-based models will have profound implications. Data will be traceable, creators will be able to retain control of their works, and copies will know they are copies. Piracy and copyright debates will be turned on their heads, as the focus shifts from copying to the real question of who can access what. Data traceability could also help counter the spread of viral rumors and inaccurate news reports.

Issues like anonymity, data security and personal privacy will require a radical rethink. But wouldn’t it be empowering to control your own information and who can access it? There’s no reason why big corporations

should have control of our data. With the right general-purpose operating system that makes hosting a piece of data, recording its metadata and managing access to it as easy as sharing a photo on Facebook, we will all be empowered to embrace our digital futures like never before.

Photo: Filing Cabinet by Robin Kearney, on Flickr

Related: