In 1993, Peter Steiner famously wrote in the New Yorker that “on the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” In 2011, trillions of dollars in e-commerce transactions and a growing number of other interactions have made knowing that someone is not only human, but a particular individual, increasingly important.

Governments are now faced with complex decisions in how they approach issues of identity, given the stakes for activists in autocracies and the increasing integration of technology into the daily lives of citizens. Governments need ways to empower citizens to identify themselves online to realize both aspirational goals for citizen-to-government interaction and secure basic interactions for commercial purposes.

It is in that context that the United States federal government introduced the final version of its National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC) this spring. The strategy addresses key trends that are crucial to the growth of the Internet operating system: online identity, privacy, and security.

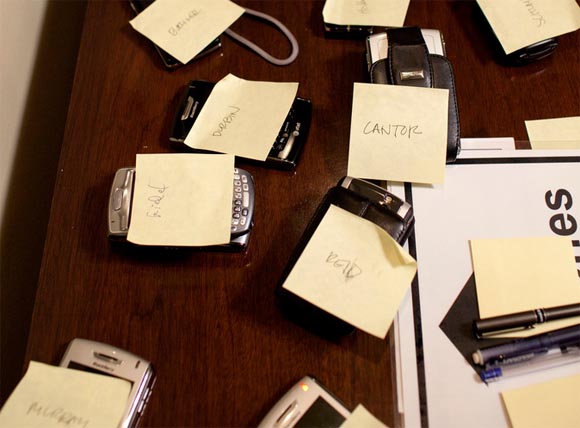

Image Credit: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

The NSTIC proposes the creation of an “identity ecosystem” online, “where individuals and organizations will be able to trust each other because they follow agreed upon standards to obtain and authenticate their digital identities.” The strategy puts government in the role of a convener, verifying and certifying identity providers in a trust framework.

First steps toward this model, in the context of citizen-to-government authentication, came in 2010 with the launch of the Open Identity Exchange (OIX) and a pilot at the National Institute of Health of a trust frameworks — but there’s a very long road ahead for this larger initiative. Online identity, as my colleague Andy Oram explored in a series of essays here at Radar, is tremendously complicated, from issues of anonymity to digital privacy and security to more existential notions of insight into the representation of our true selves in the digital medium.

NSTIC and online identity

The need to improve the current state of online identity has been hailed at the highest levels of government. “By making online transactions more trustworthy and better protecting privacy, we will prevent costly crime, we will give businesses and consumers new confidence, and we will foster growth and untold innovation,” President Obama said in a statement on NSTIC.

The final version of NSTIC is a framework that lays out a vision for an identity ecosystem. Video of the launch of the NSTIC at the Commerce Department is embedded below:

“This is a strategy document, not an implementation document,” said Ian Glazer, research director on identity management at Gartner, speaking in an interview last week. “It’s about a larger vision: this where we want to get to, these are the principles we need to get there.”

Jim Dempsey of the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) highlighted a critical tension at a forum on NSTIC in January: government needs a better online identity infrastructure to improve IT security, online privacy, and support e-commerce but can’t create it itself.

Andy Ozment, White House Director for Cybersecurity Policy, said in a press briefing prior to the release of NSTIC that the strategy was intended to protect online privacy, reduce identity theft, foster economic growth on the Internet and create a platform for the growth of innovative identity services.

“It must be led by the private sector and facilitated by government,” said Ozment. “There will be a sort of trust mark — it may not be NSTIC — that certifies that solutions will have gone through an accreditation process.”

Instead of creating a single online identity for each citizen, NSTIC envisions an identity ecosystem with many trusted providers. “In the EU [European Union] mentality, identity can only exist if the state provides it,” said Glazer. “That’s inherently an un-American position. This is frankly an adoption of the core values of the nation. There’s a rugged individualism in what we’re incorporating into this strategy.”

Glazer and others who have been following the issue closely have repeatedly emphasized that NSTIC is not a mandate to create a national online identity for every American citizen. “NSTIC puts forth a vision where individuals can choose to use a smaller number of secure, privacy-preserving online identities, rather than handing over a new set of personal information each time they sign up for a service,” said Leslie Harris, president for the Center for Democracy and Technology, in a prepared statement. “There are two key points about this Strategy: First, this is NOT a government-mandated, national ID program; in fact, it’s not an identity ‘program’ at all,” Harris said. “Second, this is a call by the Administration to the private sector to step up, take leadership of this effort and provide the innovation to implement a privacy-enhancing, trusted system.”

Harris also published a guest post at Commerce.gov that explored how the national identity strategy “envisions a more trustworthy Internet.”

The NSTIC was refined in an open government consultation process with multiple stakeholders over the course of the past year, including people from private industry, academics, privacy advocates and regulators. It is not a top-down mandate but instead a set of suggested principles that its architects hope will lead to a health identity ecosystem.

“Until a competitive marketplace and proper standards are adopted across industry, we actually continue to have fewer options in terms of how we secure our accounts than more,” said Chris Messina in an interview with WebProNews this year. “And that means that the majority of Americans will continue using the same set of credentials over and over again, increasing their risk and exposure to possible leaks.”

For a sense of the constituencies involved, read through what they’re saying about NSTIC at NIST.gov. Many of those parties are involved in an ongoing open dialogue on NSTIC at NSTIC.us.

“The commercial sector is making progress every week, every month, with players for whom there’s a lot of money involved,” said Eric Sachs, product manager for the Google Security team and board member of the OpenID Foundation, in an interview this winter. “These players have a strong expectation of a regulated solution. That’s one reason so many companies are involved in the OpenID Foundation. Businesses are finding that if they don’t offer choices for authentication, there’s significant push back that affects business outcomes.”

Functionally, there will now be an NSTIC program office in the Department of Commerce and a series of roundtables held across the United States over the next year. There will be funding for more research. Beyond that, “milestones are really hard to see in the strategy,” said Glazer. “We tend to think of NSTIC’s goal as a single, recognizable state. Maybe we should be thinking of this as DARPA for identity. It’s us as a nation harnessing really smart people on all sides of transactions.”

Improving online identity will require government and industry to work together. “One role government can play is by aggregating citizen demand and asking companies to address it,” said Sachs. “Government is doing well by coming to companies and saying that this is an issue that affects everyone on the Internet.”

NSTIC and online privacy

There are serious risks to getting this wrong, as the Electronic Frontier Foundation highlighted in its analysis of the federal online identity plan last year. The most contentious issue with NSTIC lies in its potential to enable new harms instead of preventing them, including increased identity theft.

“While we’re concerned about the unsolved technological hurdles, we are even more concerned about the policy and behavioral vulnerabilities that a widespread identity ecosystem would create,” wrote Aaron Titus of Identity Finder, which has released a 39-page analysis of NSTIC’s effect on privacy:

We all have social security cards and it took decades to realize that we shouldn’t carry them around in our wallets. Now we will have a much more powerful identity credential, and we are told to carry it in our wallets, phones, laptops, tablets and other computing devices. Although NSTIC aspires to improve privacy, it stops short of recommending regulations to protect privacy. The stakes are high, and if implemented improperly, an unregulated Identity Ecosystem could have a devastating impact on individual privacy.

It would be a mistake, however, to “freak out” over this strategy, as Kaliya Hamlin has illuminated in her piece on the NSTIC in Fast Company:

There [are] a wide diversity of use cases and needs to verify identity transactions in cyberspace across the public and private sectors. All those covering this emerging effort would do well to stop just reacting to the words “National,” “Identity,” and “Cyberspace” being in the title of the strategy document but instead to actually talk to the the agencies to understand real challenges they are working to address, along with the people in the private sector and civil society that have been consulted over many years and are advising the government on how to do this right.

So no, the NSTIC is not a government ID card, although information cards may well be one of the trusted sources of for online identity in the future, along with smartphones and other physical tokens.

The online privacy issue necessarily extends far beyond whatever NSTIC accomplishes, affecting every one of the billions of people now online. At present, the legal and regulatory framework that governs the online world varies from state to state and from sector to sector. While the healthcare and financial world have associated penalties, online privacy hasn’t been specifically addressed by legislation.

As online privacy debates heat up again in Washington when Congress returns from its spring break, that may change. Following many of the principles advanced in the FTC privacy report and the Commerce Department’s privacy report last year, Senator John McCain and Senator Kerry introduced an online privacy bill of rights in March.

After last week’s story on the retention of iPhone location data, location privacy is also receiving heightened attention in Washington. The Federal Trade Commission, with action on Twitter privacy in 2010 and Google Buzz in 2011, has moved forward without a national consumer privacy law. “I think you’ll see some enforcement actions on mobile privacy in the future,” Maneesha Mithal, associate director of the Division of Privacy and Identity Protection, told Politico last week.

For companies to be held more accountable for online privacy breaches, however, the U.S. Senate would need to move forward on H.R. 2221, the Data Accountability and Trust Act (DATA) that passed the U.S. House of Representatives this year. To date, the 112th Congress has not taken up a national data breach law again, although such a measure could be added to a comprehensive cybersecurity bill.

NSTIC and security

“The old password and user-name combination we often use to verify people is no longer good enough. It leaves too many consumers, government agencies and businesses vulnerable to ID and data theft,” said Commerce Secretary Gary Locke during the strategy launch event at the Commerce Department in Washington, D.C.

The problem is that “people are doing billions of transactions with LOA1 [Level of Assurance 1] credentials already,” said Glazer. “That’s happening today. It’s costing business to go verify these things before and after the transaction, and the principle of minimization is not being adhered to. “

Many of these challenges, however, come not from the technical side but from the user experience and business balance side, said Sachs. “Most businesses shouldn’t be in the business of having passwords for users. The goal is educating website owners that unless you specialize in Internet security, you shouldn’t be handling authentication.”

Larger companies “don’t want to tie their existence to a single company, but the worse they’re doing in a given quarter, the more willing they are to take that risk,” Sachs said.

“One username and password for everything is actually very bad ‘security hygiene,’ especially as you replay the same credentials across many different applications and contexts (your mobile phone, your computer, that seemingly harmless iMac at the Apple store, etc),” said Messina in the WebProNews interview. “However, nothing in NSTIC advocates for a particular solution to the identity challenge — least of all supporting or advocating for a single username and password per person.”

“If you look at the hopes of the NSTIC, it moves beyond passwords,” said Glazer. “My concern is that it’s authenticator-fixated. Let’s make sure it’s not solely smartcards or one-time passwords.” There won’t be a magic bullet here, as is the same conclusion faced by so many other great challenges for government and society.

Some of the answers to securing online privacy and identity, however, won’t be technical or legislative at all. They will lie in improving the digital literacy of all online citizens. That very human reality was highlighted after the Gawker database breach last year, when the number of weak passwords used online became clear.

“We’re going to set the behavior for the next generation of computing,” said Glazer. “We shouldn’t be obsessed with one or two kinds of authenticators. We should have a panoply. NSTIC is aimed at fostering the next generation of behaviors. It will involve designers, psychologists, as well as technologists. We, the identity community, need to step out of the way when it comes to the user experience and behavioral architecture.

NSTIC and the future of the Internet

NSTIC may be the “wave of the future” but, ultimately, the success or failure of this strategy will rest on several factors, many of them lying outside of government’s hands. For one, the widespread adoption of Facebook’s social graph and Facebook Connect by developers means that the enormous social network is well on its way to becoming an identity utility for the Internet. For another, the loss of anonymity online would have dire consequences for marginalized populations or activists in autocratic governments.

Ultimately, said Glazer, NSTIC may not matter in the ways that we expect it to. “I think what will come of this is a fostering of research at levels, including business standards, identity protocols and user experience. I hope that this will be a Manhattan Project for identity, but done in the public eye.”

There may be enormous risks to getting this wrong, but then that was equally true of the Apollo Project and Manhattan Project, both of which involved considerably more resources. If the United States is to enable its citizens to engage in more trusted interactions with government systems online, something better than the status quo will have to emerge. One answer will be services like Singly and the Locker Project that enable citizens to aggregate Internet data about ourselves, empowering people with personal data stores. There are new challenges ahead for the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), too. “NIST must not only support the development of standards and technology, but must also develop the policy governing the use of the technology,” wrote Titus.

What might be possible? Aaron Brauer-Rieke, a fellow at the Center for Democracy and Technology, described a best-case scenario to Nancy Scola of techPresident:

I can envision a world where a particularly good trust framework says, “Our terms of service that we will take every possible step to resist government subpoenas for your information. Any of the identity providers under our framework or anyone who accepts information from any of our identity providers must have those terms of service, too.” If something like that gains traction, that would be great.

That won’t be easy, but the potential payoffs are immense. “For those of us interested in the open government space, trusted identity raises the intriguing possibility of creating threaded online transactions with governments that require the exchange of only the minimum in identifying information,” writes Scola at techPresident. “For example, Brauer-Rieke sketched out the idea of an urban survey that only required a certification that you lived in the relevant area. The city doesn’t need to know who you are or where, exactly, you live. It only needs to know that you fit within the boundaries of the area they’re interested in.”

Online identity is, literally, all about us. It’s no longer possible for governments, businesses or citizens to remain static with the status quo. To get this right, the federal government is taking the risk of looking to the nation’s innovators to create better methods for trusted identity and authentication. In other words, it’s time to work on stuff that matters, not making people click on more ads.

Related: