Earlier this year, LinkedIn launched InMaps, a data tool that allows users to visualize their professional networks. The tool takes users’ existing data — the connections they have on LinkedIn — and clumps it into color-coded groups based on the different sorts of networks in which people belong or have belonged.

I spoke with Ali Imam (@aliimam), senior data scientist at LinkedIn, about where the idea for the tool came from, the data and technologies behind the visualizations, and how InMaps could evolve.

Our interview follows.

Where did the idea for InMaps come from?

Ali Imam: A lot of people talk about the social graph and whatnot, but we haven’t seen a really useful way to look at a social network or a professional network.

At first, creating a map or a graph of what a network looks like was one of those side projects I thought I’d work on based on my own information, but it turned into something that was far more insightful and useful. Even more than that, it’s like mathematical art. It’s a beautiful thing.

And so I started looking at a few colleagues’ networks just to show them what they looked like. It was soon clear that I wasn’t the only one who saw something useful in the visualizations.

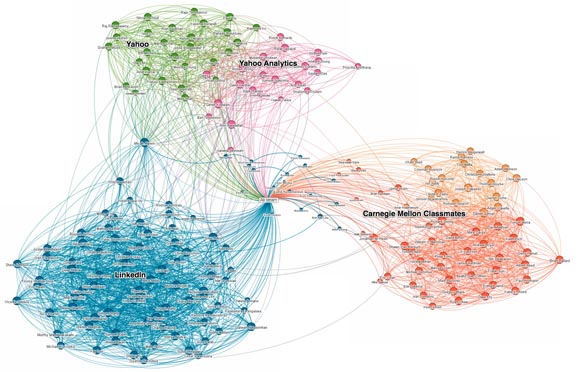

Ali Imam’s InMap. Click to enlarge.

What have you learned from your own InMap?

Ali Imam: You’ll already know, of course, that you know a lot of people at company X or Y. Or in my case, if you’re looking at my map (above), that I know a ton of people from Carnegie Mellon. But what I might not have realized is how intermingled that group is or how separate they are from the rest of my professional career.

I used to work at Yahoo before I came to LinkedIn. If you look at my map, you can see there’s a separate group within the Yahoo cluster in my network — that’s the analytics team I used to work with. You can see that this group was more heavily connected to each other than the rest of Yahoo. I was able to piece together that this particular group is slightly different than the rest of Yahoo, even though, as part of the entire Yahoo team, they’re all pretty close together.

How does InMaps work?

Ali Imam: It’s a simple premise. The idea is I’m grabbing all of the people I know, and I’m seeing who in my network they know — basically, how my contacts know each other. That’s the only data I’m pulling into this. This is a purely data-driven product where you’re looking at the intermingling of connections, and because of that, we’re using some forces on that which push apart or attract based on those connections. And that’s what forms the clusters you see in the map.

Because the people in my old Yahoo analytics team connected more to each other than the other folks at Yahoo that I’ve worked with, it makes sense that they’re more tightly connected to each other. But there are also people that I worked with at Yahoo who are now also at LinkedIn, and you can see in my network that they’re being pulled away from the Yahoo cluster and into my LinkedIn cluster. They’re bridging these two groups. They’re also green, as they’re more highly connected to members of my Yahoo network than those in my LinkedIn network. Eventually they’ll turn blue like the rest of my LinkedIn connections.

OSCON Data 2011, being held July 25-27 in Portland, Ore., is a gathering for developers who are hands-on, doing the systems work and evolving architectures and tools to manage data. (This event is co-located with OSCON.)

OSCON Data 2011, being held July 25-27 in Portland, Ore., is a gathering for developers who are hands-on, doing the systems work and evolving architectures and tools to manage data. (This event is co-located with OSCON.)

The data behind these maps is updated weekly. So if you visit every Monday or Tuesday, you’ll have a lag of 20 seconds before something loads up because we’re doing additional computation in the back before showing your network. You’ll see changes over time. For example, a few weeks ago, my Carnegie Mellon network was split into two groups, but over the course of those two weeks, there was an alumni get-together back in Pittsburgh and a lot of my friends interconnected with each other and transformed those two groups into one group.

In terms of the technology, we use Hadoop to perform a lot of our computations. Again, the idea is to grab all of my contacts and all of their interconnections. From there, there’s quite a bit of math. We use a derivation of a Barnes-Hut algorithm, which people use for physics or population applications. If a node is connected to another node, they attract each other. If they’re not connected, they push apart. By doing this with all of the connections, you start getting a layout.

There’s another algorithm we use for coloring the InMaps. It assess who people are connected to in a network and by how much. The algorithm bases the color on a percentage of “belongingness” to a certain cluster and to a certain color.

Finally, there’s the size of each person’s dot. This is based on a count of how many connections you have overlapping. The bigger the node, the more you have overlapping, and the more it becomes important in your network.

How do you see InMaps developing in the near future?

Ali Imam: The great thing about this algorithm is that it’s all about relationships. It will always evolve for every single customer of LinkedIn because every time you add a connection, you’re essentially changing your InMap.

In terms of feature sets or just what else we could do with it, we get a lot of suggestions, such as timelines or weighting different influencers or nodes. We also get asked about printing and hanging InMaps on office walls — people want to showcase their networks. Right now, you can share your InMap on Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook, so that’s the proxy for posting it in your office.

This interview was edited and condensed.

Related: