Editor’s note: This is the second post in a series looking at beacon technology and the burgeoning beacon ecosystem.

In the first of this series, I covered some of the basics behind proximity, Bluetooth Low Energy, and iBeacon, and walked through some use cases where proximity and iBeacon have started showing up in retail, travel, and other applications.

While iBeacon has arguably galvanised the notion of using proximity in applications and services, it’s not the only game in town.

In this post, I’ll cover one of the alternatives to Apple’s iBeacon, Physical Web from Google, and then I’ll zoom out to look at the flurry of activity in startups in the evolving “Beacosystem.”

First, a small recap on what helped iBeacon gain so much traction, so quickly and helped shape the landscape for a proximity ecosystem to emerge.

Creating an ecosystem

Apple’s iBeacon is a layer, or a “convention,” that builds on the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Standard. Apple has spurred an ecosystem around iBeacon by doing several things, which all feed into each other:

- Baked support for iBeacon into its mobile operating system (iOS) so that APIs are readily available for developers.

- Included support for background notifications at the OS level, so that push notifications can be triggered in certain situations, but without killing your phone’s battery.

- Provided a certification program to enable hardware manufacturers to create iBeacon-compatible hardware. This allows third-party manufacturers to provide iBeacon-compatible hardware of all shapes, sizes, and form factors, At last count, there were more than 50 suppliers of iBeacon hardware.

- Enabled every iOS device to be an iBeacon. This has many potential uses, from iPad-based POS systems welcoming you to a store, to the Hailo App letting you know that you can pay by Hailo.

- Ate its own dog food, by using iBeacon with their Apple Store App in all their US based Apple Stores.

Slide image courtesy of Sean O Sullivan.

Taken together, the Apple hardware and software platform is pretty well set up to drive and support a wide range of proximity experiences.

So, where do Google and Android fit in the picture?

iBeacon: Not the only game in town

Google has taken a different approach to proximity, which in its own way, may end up having as great an impact as iBeacon. In October 2014, Google launched a project called Google Physical Web with a simple and short Web page that described it, and a link to the technical details on Github. They position it as “interaction on demand,” and the project has the tagline: “walk up and use anything.”

A few things distinguish Google’s approach from Apple’s, so far:

- It’s a Google project right now, not a Google product

- It’s an open source project, hosted at GitHub, so “everyone can contribute”

- It aspires to be an open standard, not controlled by a single company

- It’s Web-centric — where iBeacon advertises UUIDs and Major/Minor codes to devices nearby, instead Physical Web Beacons send URLs

- It’s not intended to proactively alert or notify the user (so no ad-hoc alerts, and no background scanning when the phone is in your pocket)

Slide image courtesy of Sean O Sullivan.

What Physical Web has in common with iBeacon is that it, too, uses BLE to send (advertise) URLs to “whomever is interested” nearby. The use of the URL ties the approach to Google’s native home turf of “the Web,” and also provides a easy hook for everyone to understand the concept: what if physical things could send out a URL to tell you all about themselves?

In the documents describing the Physical Web, Google takes aim at some of the potential issues with iBeacon, including the emphasis on being open as opposed to being controlled by one company, and not being “interrupt” driven.

Instead the user “pulls” information only when they go looking for it, and the system reacts by offering information about whatever “things nearby” support the Physical Web. One of the key tenets of the approach that Google has taken with Physical Web is that in the IoT era, it’s just not possible, or desirable, to have an app for every single device that’s connectable. Think for example about a typical home, that could have 150 connected devices. Must I have an app for each one? No thanks. Google’s approach suggests an alternative, where a user can “discover” devices nearby, then just interact with them when needed.

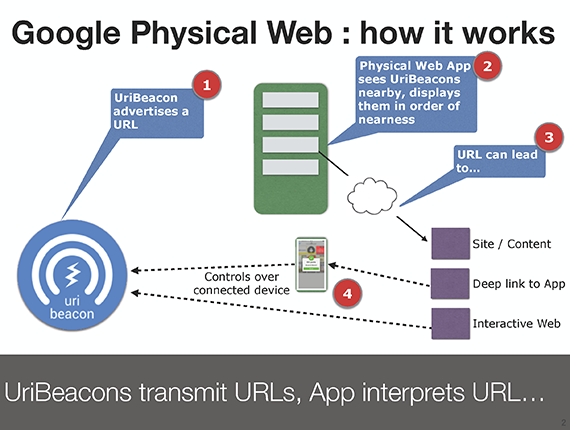

How Google Physical Web works

As with iBeacon, at the core of Physical Web, is a BLE beacon that advertises a URL. The URL is encoded in a particular way and is sent in the advertising packet transmitted by the beacon. Google specifies the formatting, and they refer to a beacon that complies with the required formatting as a “UriBeacon” (pronounced YUR-ee-BEE-kun).

Right now, the client that detects the URL advertised by a UriBeacon is an application that runs on one or more devices (there are several clients available, on Android, iOS, and other platforms). The client app lists the nearby UriBeacons that it can “see,” and displays associated information (title, description, URL, etc.). The user can tap on the URL to “follow” that URL to its destination. The URL may lead to a simple Web page (with some basic information or content), an interactive website (perhaps with controls for the device in question), or a deep link in to a mobile application. The use of the URL gives the system some of its most interesting potential, as it provides a simple but flexible way of “jumping off” to any given endpoint on the Web. Simple, but powerful.

In time, depending on how the project evolves, the app can disappear, and instead, the ability to sense and react to nearby UriBeacons could be integrated with the Android OS, ChromeOS, and perhaps with built-in Google Apps on Android, such as Chrome.

Slide image courtesy of Sean O Sullivan.

A number of companies now sell ready-to-run UriBeacons that comply to the Physical Web UriBeacon specification. These include Blesh, Accent Systems, KST, and others. In addition, those looking for lower level control over their own UriBeacons can flash their own firmware for a variety of popular hardware devices, such as Arduino and Raspberry Pi.

Up next for Physical Web

Google did not rush in to the proximity party. Physical Web first appeared as a public project in September 2014, around 15 months after the first mention of iBeacon appeared from Apple at their WWDC conference. Today, it remains a project, as opposed to a product, with widespread support across the deployed Google ecosystem. However, it seems likely that this will change, and we may see new developments around Physical Web at their upcoming Google I/O conference in May 2015. Google has the potential to “switch on” support for Physical Web in their mobile products, such as Android and their mobile browser variants. There are many industries and verticals very interested in an “app-free” proximity solution, and with Physical Web, Google has an option to deliver a solution at scale, albeit only on its own mobile platform.

Aside from Apple and Google, the only other significant player to emerge with an offering is Samsung, who launched Samsung Proximity in November 2014. They wrapped up the proximity services in a branded platform “Placedge,” which, like both Apple and Google, uses BLE beacons to enable proximity-powered applications and services.

In this case, Samsung is also proposing to require no app, and instead would bake support for proximity in to their own suite of mobile hardware and software products. However, after initial launch at the end of 2014, not much has been heard in terms of real product rollout, and the contact details listed at their website now bounce. There’s also a notice stating that Placedge SDK will not be distributed in public any more. So, it’s possible that Placedge is currently in limbo for the time being, pending further announcements.

The Beacosystem: Startups, movers, and shakers

Since 2009, when we first developed our proximity platform LocalSocial, we have been tracking companies of different kinds who were working in the same “space” — either adjacent to us, complementary in terms of offerings (so we could perhaps partner), or directly competitive. Back in the early days, the competitors were thin on the ground. It was us, and perhaps three other companies.

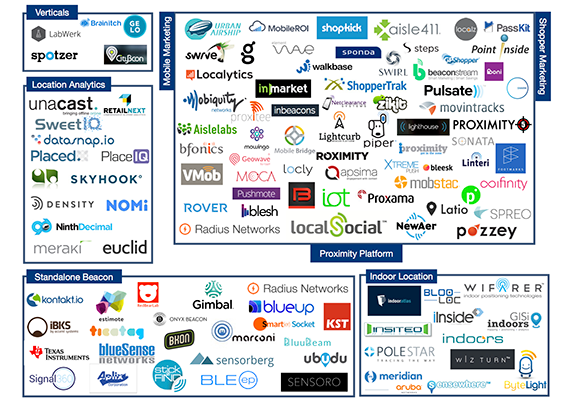

Today, depending on how you define the same “space,” there are around 150 or more companies offering some element of proximity to the market: hardware, SDK, platform, or some combination of all of these, wrapped into a generic or vertical solution. To help make some sense of this explosion in companies, we began to chart them in our own “Lumascape” picture, and share them online for feedback. We called the picture with its accompanying analysis the “Beacosystem”:

Slide image courtesy of Sean O Sullivan.

We grouped the companies into the following broad categories, some of which overlap in various ways:

- Hardware: this includes any of the companies that manufacture beacon hardware, including Estimote, Kontakt, Radius, Gimbal, and others. Some of the hardware manufacturers focus only on hardware, while others are building out broader offerings that include Developer SDKs, Cloud-based Content Management Systems (CMS), Analytics, and more.

- Indoor location: A number of companies are using BLE and iBeacons primarily as part of an indoor location platform solution: a “GPS for Indoor use.” They use a mix of technology, including beacons, to do this. Indoors, Meridian/Aruba, and ByteLight are examples of companies using beacons as an element of their solution for delivering indoor location solutions to various verticals.

- Shopper/retail-centric: Retail has, to some extent, dominated the initial period of coverage about beacon technology and iBeacon, and that’s reflected in the number of companies positioning themselves specifically as solutions for retail or shopper marketing. ShopKick was a genuine pioneer in this area, and companies such as Aisle411, InMarket, Swirl, and ShopperTrak have all built out offerings tuned to the needs of retailers and brands.

- Mobile marketing: A number of companies are using beacons as signals that can be used within a broader mobile marketing platform. Urban Airship, the “daddy of push notifications” was early to the fray here, but has been joined by Swrve, Localytics, and others in this quickly expanding space.

- Proximity platforms: Some companies (ours included) offer a more general-purpose proximity platform, not tied to a specific vertical, and often open via APIs to work with various other players in the ecosystem. Radius, IOT, MOCA, and others all have offerings that comprise software, APIs, and devkits that let third parties build whatever proximity-enabled application or service that interests them.

I’m now updating our picture of the Beacosystem, as the area continues to evolve rapidly. In the last post in this series, I’ll look at some of the issues in using and deploying beacon-based solutions, some of the trends in both hardware and software offerings, and share some resources where you can find more detail on everything I’ve covered so far.