Mike Loukides

Do one thing…

I don't want barely distinguishable tools that are mediocre at everything; I want tools that do one thing and do it well.

I’ve been lamenting the demise of the Unix philosophy: tools should do one thing, and do it well. The ability to connect many small tools is better than having a single tool that does everything poorly.

I’ve been lamenting the demise of the Unix philosophy: tools should do one thing, and do it well. The ability to connect many small tools is better than having a single tool that does everything poorly.

That philosophy was great, but hasn’t survived into the Web age. Unfortunately, nothing better has come along to replace it. Instead, we have “convergence”: a lot of tools converging on doing all the same things poorly.

The poster child for this blight is Evernote. I started using Evernote because it did an excellent job of solving one problem. I’d take notes at a conference or a meeting, or add someone to my phone list, and have to distribute those files by hand from my laptop to my desktop, to my tablets, to my phone, and to any and all other machines that I might use.

But as time has progressed, Evernote has added many other features. Some I might have a use for, but they’re implemented poorly; others I’d rather not have, thank you. I’ve tried sharing Evernote notes with other users: they did a good job of convincing me not to use them. Photos in documents? I really don’t care. When I’m taking notes at a conference, the last thing I’m thinking about is selfies with the speakers. Discussions? No, please no. There are TOO MANY poorly implemented chat services out there. We can discuss my shared note in email. Though, given that it’s a note, not a document, I probably don’t want to share anyway. If I wanted a document, even a simple one, I’d use a tool that was really good at preparing documents. Taking notes and writing aren’t the same, even though they may seem similar. Nor do I want to save my email in Evernote; I’ve never seen, and never expect to see, an email client that didn’t do a perfectly fine job of saving email. Clippings? Maybe. I’ve never particularly wanted to do that; Pinboard, which has stuck to the “do one thing well” philosophy, does a better job of saving links. Read more…

Amazon, boredom, and culture

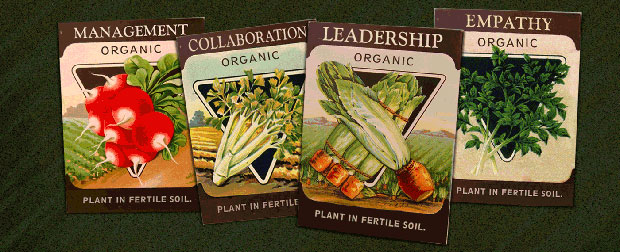

Corporate leadership is as much about building people as it is about developing product.

Attend Cultivate, September 28 to 29 in New York, NY. Cultivate is our conference looking at the challenges facing modern management and aiming to train a new generation of business leaders who understand the relationship between corporate culture and corporate prosperity.

I want to call attention to two articles I’ve read recently. First, Rita King’s analysis of Amazon’s corporate culture, Culture Controversy at Amazon, Decoded, is an excellent, even-handed discussion of one of the past year’s most controversial articles about corporate culture. I hadn’t intended to write about Amazon, but King’s article needs to be read.

King doesn’t present a simple “bad Amazon” story. Anyone in the industry knows that Amazon is a tough place to work. King presents both sides of this picture: working at Amazon is difficult and demanding, but you may find yourself pushed to levels of creativity you never thought possible. Amazon’s culture encourages a lot of critical thinking, questioning, and criticism, sometimes to the point of “brutality.” This pressure can lead to backstabbing and intense rivalries, and I’m disturbed by Amazon’s myth that they are a “meritocracy,” since meritocracies rarely have much to do with merit. But the result of constant pressure to perform at the highest level is that Amazon can move quickly, react to changes, and create new products faster than its competitors — often before their competitors even realize there’s an opportunity for a new product.

Without pressure to achieve, and without critical thinking, it’s easy to build a culture of underachievers, a culture of complacency. A culture of complacency is more comfortable, but in the long run, just as ugly. DEC, Wang, and a host of other high-tech companies from the 70s and 80s never understood how the industry was changing until it was too late. HP is arguably in a similar position now. I can’t see Amazon making the same mistake. When you’re making the changes, you’re less likely to be done in by them. Read more…

Cultivate in Portland: Leadership, values, diversity

Building the next generation of leaders, for any size organization.

Register now for Cultivate NY, which will be co-located with Strata + Hadoop World NY, September 28 and 29, 2015.

At our recent Cultivate event in Portland, O’Reilly and our partnering sponsor New Relic brought together 10 speakers and more than 100 attendees to learn about corporate culture and leadership. Three themes emerged: diversity, values, and leading through humility.

Almost every speaker talked about the importance of diversity in the workplace. That’s important at a time when “maintaining corporate culture” often means building a group that’s reminiscent of a college frat house. It’s well established that diverse groups, groups that include different kinds of people, different experiences, and different ways of thinking, perform better. As Michael Lopp said at the event, “Diversity is a no-brainer.” We’re not aiming for tribal uniformity, but as Mary Yoko Brannen noted at the outset, sharing knowledge across different groups with different expectations. No organization can afford to remain monochromatic, but in a diverse organization, you have to be aware of how others differ. In particular, Karla Monterroso showed us that you need to realize when — and why — others feel threatened. When you do, you are in a much better position to build better products, to respond to changes in your market, and to use the talent in your organization effectively. Read more…

Imagining a future biology

We need to nurture our imaginations to fuel the biological revolution.

Download the new issue of BioCoder, our newsletter covering the biological revolution.

I recently took part in a panel at Engineering Biology for Science & Industry, where I talked about the path biology is taking as it becomes more and more of an engineering discipline, and how understanding the path electronics followed will help us build our own hopes and dreams for the biological revolution.

I recently took part in a panel at Engineering Biology for Science & Industry, where I talked about the path biology is taking as it becomes more and more of an engineering discipline, and how understanding the path electronics followed will help us build our own hopes and dreams for the biological revolution.

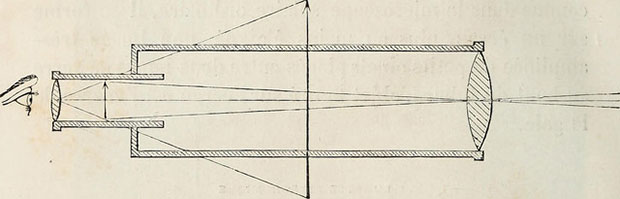

In 1901, Marconi started the age of radio, and really the age of electronics, with the “first” trans-atlantic radio transmission. It’s an interesting starting point, because important as this event was, there’s good reason to believe that it never really happened. We know a fair amount about the equipment and the frequencies Marconi was using: we know how much power he was transmitting (a lot), how sensitive his receiver was (awful), and how good his antenna was (not very).

We can compute the path loss for a signal transmitted from Cornwall to Newfoundland, subtract that from the strength of the signal he transmitted, and compare that to the sensitivity of the receiver. If you do that, you have to conclude that Marconi’s famous reception probably never happened. If he succeeded, it was by means of a fortunate accident: there are several possible explanations for how a radio signal could have made it to Marconi’s site in Newfoundland. All of these involve phenomenon that Marconi couldn’t have known about. If he succeeded, his equipment, along with the radio waves themselves, were behaving in ways that weren’t understood at the time, though whether he understood what was happening makes no difference. So, when he heard that morse code S, did he really hear it? Did he imagine it? Did he lie? Or was he very lucky? Read more…

To suit or not to suit?

At Cultivate, we'll address the issues really facing management: how to deal with human problems.

Attend Cultivate July 20 and 21, in Portland, Oregon, which will be co-located with our OSCON Conference. Cultivate is our event looking at the challenges facing modern management and aiming to train a new generation of business leaders who understand the relationship between corporate culture and corporate prosperity.

What does it take to become a manager? According to one article, you should buy a suit. And think about whether you want to be a manager in the first place. You’re probably being paid better as a programmer. Maybe you should get an MBA. At night school. And take a Myers-Briggs test.

What does it take to become a manager? According to one article, you should buy a suit. And think about whether you want to be a manager in the first place. You’re probably being paid better as a programmer. Maybe you should get an MBA. At night school. And take a Myers-Briggs test.

There are better ways to think about management. Cultivate won’t tell you how to become a manager, or even whether you should; that’s ultimately a personal decision. We will discuss the issues that are really facing management: issues that are important whether you are already managing, are looking forward to managing, or just want to have a positive impact on your company.

Management isn’t about technical issues; it’s about human issues, and we’ll be discussing how to deal with human problems. How do you debug your team when its members aren’t working well together? How do you exercise leadership effectively? How do you create environments where everyone’s contribution is valued?

These are the issues that everyone involved with the leadership of a high-performance organization has to deal with. They’re inescapable. And as companies come under increasing pressure because of ever-faster product cycles, difficulty hiring and retaining excellent employees, customer demand for designs that take their needs into account, and more, these issues will become even more important. We’ve built Cultivate around the cultural changes organizations will need to thrive — and in many cases, survive — in this environment. Read more…

Flattening organizations

It's easy to talk about eliminating hierarchy; it's much harder to do it effectively.

Attend Cultivate July 20 and 21, in Portland, Oregon, which will be co-located with our OSCON Conference. Cultivate is our event looking at the challenges facing modern management and aiming to train a new generation of business leaders who understand the relationship between corporate culture and corporate prosperity.

Do companies need a managerial class? The idea of a future without management takes many forms, some more sophisticated than others; but at their most basic, the proposals center around flattening organizational structure. Companies can succeed without managers and without grunts. Employees are empowered to find something useful to do and then do it, making their own decisions along the way. That vision of the future is gaining momentum, and a few businesses are taking the fairly radical step of taking their companies flat.

The game developer Valve‘s employee handbook is outspoken in its rejection of traditional corporate hierarchy. There is no management class. Teams self-organize around specific tasks; when the task is done, the team disappears and its members find new tasks. All the office furniture has wheels, so groups can self-organize at a moment’s notice. Employees rate each other, producing a ranking that is used to determine salaries.

More recently, Zappos and Medium have been in the news for adopting similar (though apparently more formalized) practices, under the name “holacracy.”

There’s a lot to like about this model, but I also have concerns. I’m no friend to hierarchy, but if I’ve seen one thing repeatedly in my near-60 years, it’s that you frequently are what you reject. By rejecting something, whether it’s hierarchy, lust for power, wealth, whatever, you make it very difficult to be self-critical. You don’t change yourself; instead, you turn what you dislike most about yourself into your blind spot. Read more…

BioBuilder: Rethinking the biological sciences as engineering disciplines

Moving biology out of the lab will enable new startups, new business models, and entirely new economies.

Buy “BioBuilder: Synthetic Biology in the Lab,” by Natalie Kuldell PhD., Rachel Bernstein, Karen Ingram, and Kathryn M. Hart.

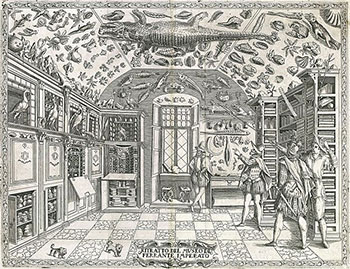

What needs to happen for the revolution in biology and the life sciences to succeed? What are the preconditions?

I’ve compared the biorevolution to the computing revolution several times. One of the most important changes was that computers moved out of the lab, out of the machine room, out of that sacred space with raised floors, special air conditioning, and exotic fire extinguishers, into the home. Computers stopped being things that were cared for by an army of priests in white lab coats (and that broke several times a day), and started being things that people used. Somewhere along the line, software developers stopped being people with special training and advanced degrees; children, students, non-professionals — all sorts of people — started writing code. And enjoying it.

Biology is now in a similar place. But to take the next step, we have to look more carefully at what’s needed for biology to come out of the lab. Read more…

Artificial intelligence?

AI scares us because it could be as inhuman as humans.

Elon Musk started a trend. Ever since he warned us about artificial intelligence, all sorts of people have been jumping on the bandwagon, including Stephen Hawking and Bill Gates.

Although I believe we’ve entered the age of postmodern computing, when we don’t trust our software, and write software that doesn’t trust us, I’m not particularly concerned about AI. AI will be built in an era of distrust, and that’s good. But there are some bigger issues here that have nothing to do with distrust.

What do we mean by “artificial intelligence”? We like to point to the Turing test; but the Turing test includes an all-important Easter Egg: when someone asks Turing’s hypothetical computer to do some arithmetic, the answer it returns is incorrect. An AI might be a cold calculating engine, but if it’s going to imitate human intelligence, it has to make mistakes. Not only can it make mistakes, it can (indeed, must be) be deceptive, misleading, evasive, and arrogant if the situation calls for it.

That’s a problem in itself. Turing’s test doesn’t really get us anywhere. It holds up a mirror: if a machine looks like us (including mistakes and misdirections), we can call it artificially intelligent. That begs the question of what “intelligence” is. We still don’t really know. Is it the ability to perform well on Jeopardy? Is it the ability to win chess matches? These accomplishments help us to define what intelligence isn’t: it’s certainly not the ability to win at chess or Jeopardy, or even to recognize faces or make recommendations. But they don’t help us to determine what intelligence actually is. And if we don’t know what constitutes human intelligence, why are we even talking about artificial intelligence? Read more…

Cultivating change

Cultivate is O'Reilly's conference committed to training the people who will lead successful teams, now and in the future.

Attend Cultivate July 20 and 21, in Portland, Oregon. Cultivate is our conference looking at the challenges facing modern management and aiming to train a new generation of business leaders who understand the relationship between corporate culture and corporate prosperity.

Leadership has changed — and in a big way — since the Web started upending the status quo two decades ago. That’s why we’re launching our new Cultivate event; we realized that businesses need new types of leaders, and that O’Reilly is uniquely positioned to help engineers step up to the job.

At the start of the 21st century, Google was in its infancy; Facebook didn’t exist; and Barnes & Noble, not Amazon, was the dominant force in the book industry. As we’ve watched these companies grow, we’ve realized that every business is a software business, and that the factors that made Google, Facebook, and Amazon successful can be applied outside the Web. Every business, from your dentist’s office to Walmart, is critically dependent on software. As Marc Andreessen put it, software is eating the world.

As companies evolve into software businesses, they become more dependent on engineers for leadership. But an engineer’s training rarely includes leadership and management skills. How do you make the transition from technical problems to management problems, which are rarely technical? How do you become an agent for growth and change within your company? And what sorts of growth and change are necessary?

The slogan “every business is a software business” doesn’t explain much, until we think about how software businesses are different. Software can be updated easily. It took software developers the better part of 50 years to realize that, but they have. That kind of rapid iteration is now moving into other products. Read more…