At this week’s Strata Conference in New York, there’s a lot of discussion about data transparency. As masses of easily available, quickly analyzed data transform businesses, that data can also change how we regulate and legislate the world.

Data transparency holds promise. It should, in theory, weed out corruption and level the playing field. Rather than regulating what a company can do, for example, we can regulate what it must share with the world — and then let the world deal with the consequences, whether by boycott, activism, or class-action lawsuit. It’s something the Leading Edge Forum’s Michael Nelson described as a form of digital libertarianism: pacts of transparency between businesses and consumers, or between governments and citizens. He calls it “Mutually Assured Disclosure.”

It’s certainly encouraging to think that corruption and shenanigans wither under the harsh light of data. With information out in the open, it should be easy for interested parties to review the numbers — using cheap clouds and intuitive visualizations — and spot the cheaters.

Does data really blow its own whistle?

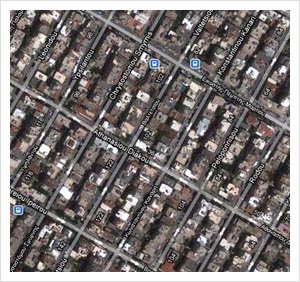

The first problem open data advocates run into is that of getting real information. Look at Greece: 324 Athenians reported having swimming pools on their taxes. When the government used Google Maps to try and count how many there really were, they found 16,974 of them — despite efforts by citizens to camouflage their pools under green tarpaulins. So even if activists can use widely available data to create change, that data may be wrong.

The first problem open data advocates run into is that of getting real information. Look at Greece: 324 Athenians reported having swimming pools on their taxes. When the government used Google Maps to try and count how many there really were, they found 16,974 of them — despite efforts by citizens to camouflage their pools under green tarpaulins. So even if activists can use widely available data to create change, that data may be wrong.

One way around this is to get your own data. The barriers to data collection have vanished with the advent of social networks, ubiquitous computing, and other innovations. Just as Greek tax officials can use Google Earth to understand tax evasion, so organizations like Asthmapolis can crowdsource data — in this case, by attaching GPS receivers to asthma inhalers — and use the information to shape public policy.

Can we tell when the data is wrong?

Data in hand, it needs to be properly analyzed. That’s not as easy as it sounds.

With software development, it’s easy to see the results. If the coder’s work isn’t effective, the finished product is buggy, unusable, slow, and incompatible. On the other hand, a lazy data scientist produces wrong results that may not be obvious to anyone. Detecting fraud or error in data sets can be tough. At Strata Summit, LinkedIn’s Monica Rogati highlighted a number of common errors that analysts make when interpreting and reporting their research; as more and more people start to work with numbers, more and more make mistakes. Statistics is often counter-intuitive. (Want a good example? Try the Monty Hall problem.)

Will we know if we’ve got bad data, whether from malice, omission, or accident? It’s possible to detect fraud in some cases. Modeling datasets often reveals problems with the data, and statisticians have tricks that can help. Benford’s Law, for example, says that “for naturally occurring data, you get more ones than twos, more twos than threes, and so on, all the way down to nine.” Point the law certain kinds of datasets, and you know how likely it is that the contents are a lie.

Will we act on it?

Open data is no good unless it leads to action. Most proponents of transparency believe that change logically flows from proof. In government, at least, current public policy suggests otherwise. On critical global issues like climate science and evolution, despite overwhelming, peer-reviewed data, we’re still deadlocked on whether to teach creationism, or whether climate change is real. Don’t like the numbers you’re getting? Call them corrupt. Threaten to take away funding. If the infographic is the new stump speech, then questioning the data is the new rebuttal.

Simply having transparency doesn’t lead to change. Without effective checks and balances, and without real punishments, shining the harsh light of data won’t do anything. This makes class action lawyers and hacktivists unlikely allies: Lawsuits, social media campaigns, and boycotts are often the only way to induce change from otherwise unregulated industries.

Data transparency is an arms race. In a world of full disclosure, cooking the data is the new cooking the books. How many of today’s data scientists will become tomorrow’s forensic accountants, locked in a war with the fraudulent and the ignorant? Open data and transparency aren’t enough: we need True Data, not Big Data, as well as regulators and lawmakers willing to act on it.