Alistair Croll

Old-school DRM and new-school analytics

Piracy isn’t the threat; it’s centuries old. Music Science is the game changer.

Download our new free report “Music Science: How Data and Digital Content are Changing Music,” by Alistair Croll, to learn more about music, data, and music science.

In researching how data is changing the music industry, I came across dozens of entertaining anecdotes. One of the recurring themes was music piracy. As I wrote in my previous post on music science, industry incumbents think of piracy as a relatively new phenomenon — as one executive told me, “vinyl was great DRM.”

In researching how data is changing the music industry, I came across dozens of entertaining anecdotes. One of the recurring themes was music piracy. As I wrote in my previous post on music science, industry incumbents think of piracy as a relatively new phenomenon — as one executive told me, “vinyl was great DRM.”

But the fight between protecting and copying content has gone on for a long time, and every new medium for music distribution has left someone feeling robbed. One of the first known cases of copy protection — and illegal copying — involved Mozart himself.

As a composer, Mozart’s music spread far and wide. But he was also a performer and wanted to be able to command a premium for playing in front of audiences. One way he ensured continued demand was through “flourishes,” or small additions to songs, which weren’t recorded in written music. While Mozart’s flourishes are lost to history, researchers have attempted to understand how his music might once have been played. This video shows classical pianist Christina Kobb demonstrating a 19th century technique.

The music science trifecta

Digital content, the Internet, and data science have changed the music industry.

Download our new free report “Music Science: How Data and Digital Content are Changing Music,” by Alistair Croll, to learn more about music, data, and music science.

Today’s music industry is the product of three things: digital content, the Internet, and data science. This trifecta has altered how we find, consume, and share music. How we got here makes for an interesting history lesson, and a cautionary tale for incumbents that wait too long to embrace data.

When music labels first began releasing music on compact disc in the early 1980s, it was a windfall for them. Publishers raked in the money as music fans upgraded their entire collections to the new format. However, those companies failed to see the threat to which they were exposing themselves.

Until that point, piracy hadn’t been a concern because copies just weren’t as good as the originals. To make a mixtape using an audio cassette recorder, a fan had to hunch over the radio for hours, finger poised atop the record button — and then copy the tracks stolen from the airwaves onto a new cassette for that special someone. So, the labels didn’t think to build protection into the CD music format. Some companies, such as Sony, controlled both the devices and the music labels, giving them a false belief that they could limit the spread of content in that format.

One reason piracy seemed so far-fetched was that nobody thought of computers as music devices. Apple Computer even promised Apple Records that it would never enter the music industry — and when it finally did, it launched a protracted legal battle that even led coders in Cupertino to label one of the Mac sound effects “Sosumi” (pronounced “so sue me”) as a shot across Apple Records’ legal bow. Read more…

Consensual reality

The data model of augmented reality is likely to be a series of layers, some of which we consent to share with others.

A couple of days ago, I had a walking meeting with Frederic Guarino to discuss virtual and augmented reality, and how it might change the entertainment industry.

At one point, we started discussing interfaces — would people bring their own headsets to a public performance? Would retinal projection or heads-up displays win?

One of the things we discussed was projections and holograms. Lighting the physical world with projected content is the easiest way to create an interactive, augmented experience: there’s no gear to wear, for starters. But will it work?

This stuff has been on my mind a lot lately. I’m headed to Augmented World Expo this week, and had a chance to interview Ori Inbar, the founder of the event, in preparation.

Among other things we discussed what Inbar calls his three rules for augmented reality design:

- The content you see has to emerge from the real world and relate to it.

- Should not distract you from the real world; must add to it.

- Don’t use it when you don’t need it. If a film is better on the TV watch the TV.

To understand the potential of augmented reality more fully, we need to look at the notion of consensual realities. Read more…

Filing cabinets, GAAP, and the accountant’s dilemma

The inability to take advantage of digital technology is as big a threat to financial organizations as any fintech startup.

Learn more about Next:Money, O’Reilly’s conference focused on the fundamental transformation taking place in the finance industry.

There’s plenty of news about the fintech, or financial technology, sector these days. Hundreds of nimble startups are disaggregating the age-old financial systems on which every transaction has relied for decades. There’s little doubt that this will continue — after all, more than four billion humans have a mobile phone, and 1.3 billion know how to use a Facebook feed, but only a billion are what we’d consider “normally banked.” Something’s got to give, and software is eating traditional financial systems one bite at a time.

There’s plenty of news about the fintech, or financial technology, sector these days. Hundreds of nimble startups are disaggregating the age-old financial systems on which every transaction has relied for decades. There’s little doubt that this will continue — after all, more than four billion humans have a mobile phone, and 1.3 billion know how to use a Facebook feed, but only a billion are what we’d consider “normally banked.” Something’s got to give, and software is eating traditional financial systems one bite at a time.

But the existing financial industry isn’t just under threat from outside. Many of the processes and institutions of finance have been around for centuries, and their processes are tied to physical systems rather than digital ones. As a result, they’re unable to take advantage of digital innovations easily and remain competitive. Read more…

9.3 trillion reasons fintech could change the developing world

Modern fintech is going to create formal, standard records about economies where none existed before.

Learn more about Next:Money, O’Reilly’s conference focused on the fundamental transformation taking place in the finance industry.

A relatively commonplace occurrence — credit card fraud — made me reconsider the long-term impact of financial technology outside the Western world. I’ll get to it, but first, we need to talk about developing economies.

I’m halfway through Hernand de Soto’s The Mystery of Capital on the advice of the WSJ’s Michael Casey. Its core argument is that capitalism succeeds in the Western world and fails everywhere else because in the West, property can be turned into capital (you can mortgage a house and use that money to do something). The book uses the analogy of a hydroelectric dam as a means of unlocking the hidden, potential value of the lake.

But in much of the world, it is unclear who owns what, and as a result, the value of assets can’t be put to work in markets. In the West, we take concepts like title and lien and identity for granted; yet, these systems are relatively new and don’t exist around the world. As de Soto noted in his book, in the Soviet Union, unofficial economic activity rose from 12% in 1989 to 37% in 1994. Read more…

Mind if I interrupt you?

Notification centers and Apple Watches beg the question: what’s the best way to interrupt us properly?

We’ve been claiming information overload for decades, if not centuries. As a species, we’re pretty good at inventing new tools to deal with the problems of increasing information: language, libraries, broadcast, search, news feeds. A digital, always-on lifestyle certainly presents new challenges, but we’re quickly creating prosthetic filters to help us cope.

Now there’s a new generation of information management tools, in the form of wearables and watches. But notification centers and Apple Watches beg the question: what’s the best way to interrupt us properly? Already, tables of friends take periodic “phone breaks” to check in on their virtual worlds, something that might have been considered unthinkably gauche a few years ago.

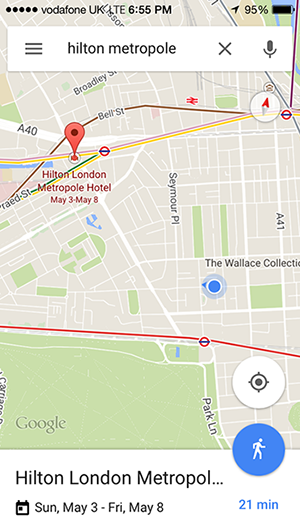

Since the first phone let us ring a bell, uninvited, in a far-off house, we’ve been dealing with interruption. Smart interruption is useful: Stewart Brand said that the right information at the right time just changes your life; it follows, then, that the perfect interface is one that’s invisible until it’s needed, the way Google inserts hotel dates on a map, or flight times in your calendar, or reminders when you have to leave for your next meeting.

Since the first phone let us ring a bell, uninvited, in a far-off house, we’ve been dealing with interruption. Smart interruption is useful: Stewart Brand said that the right information at the right time just changes your life; it follows, then, that the perfect interface is one that’s invisible until it’s needed, the way Google inserts hotel dates on a map, or flight times in your calendar, or reminders when you have to leave for your next meeting.

But all of this technology is interfering with reflection, introspection, and contemplation. In Alone Together, Sheri Turkle observes that it’s far easier to engage with tools like Facebook than it is to connect with actual humans because interactive technology’s availability makes it a junk-food substitute for actual interaction. My friend Hugh McGuire recently waxed rather poetically on the risks of constant interruption, and how he’d forgotten how to read because of it.

At work, modern productivity tools like Slack might do away with email conventions, encouraging better collaboration, but they do so at a cost because they work in a way that demands immediate attention, and that interrupts the natural rhythm we all need to write, to read, and to immerse ourselves in our surroundings. It’s hard to marinate when you’re being interrupted. Read more…

Apple Watch and the skin as interface

The success of Apple’s watch, and of wearables in general, may depend on brain plasticity.

Recently, to much fanfare, Apple launched a watch. Reviews were mixed. And the watch may thrive — after all, once upon a time, nobody knew they needed a tablet or an iPod. But at the same time, today’s tech consumer is markedly different from those at the dawn of the Web, and the watch faces a different market all together.

Apple Watches. Source: Apple.

One of the more positive reviews came from tech columnist Farhad Manjoo. In it, he argued that we’ll eventually give in to wearables for a variety of reasons.

“It was only on Day 4 that I began appreciating the ways in which the elegant $650 computer on my wrist was more than just another screen,” he wrote. “By notifying me of digital events as soon as they happened, and letting me act on them instantly, without having to fumble for my phone, the Watch became something like a natural extension of my body — a direct link, in a way that I’ve never felt before, from the digital world to my brain.”

On-body messaging and brain plasticity

Manjoo uses the term “on-body messaging” to describe the variety of specific vibrations the watch emits, and how quickly he came to accept them as second nature. The success of Apple’s watch, and of wearables in general, may be due to this brain plasticity. Read more…

Startups suggest big data is moving to the clouds

A look at the winners from a showcase of some of the most innovative big data startups.

At Strata + Hadoop World in London last week, we hosted a showcase of some of the most innovative big data startups. Our judges narrowed the field to 10 finalists, from whom they — and attendees — picked three winners and an audience choice.

Underscoring many of these companies was the move from software to services. As industries mature, we see a move from custom consulting to software and, ultimately, to utilities — something Simon Wardley underscored in his Data Driven Business Day talk, and which was reinforced by the announcement of tools like Google’s Bigtable service offering.

This trend was front and center at the showcase:

- Winner Modgen, for example, generates recommendations and predictions, offering machine learning as a cloud-based service.

- While second-place Brytlyt offers their high-performance database as an on-premise product, their horizontally scaled-out architecture really shines when the infrastructure is elastic and cloud based.

- Finally, third-place OpenSensors’ real-time IoT message platform scales to millions of messages a second, letting anyone spin up a network of connected devices.

Ultimately, big data gives clouds something to do. Distributed sensors need a widely available, connected repository into which to report; databases need to grow and shrink with demand; and predictive models can be tuned better when they learn from many data sets. Read more…

Year Zero: Our life timelines begin

In the next decade, Year Zero will be how big data reaches everyone and will fundamentally change how we live.

Editor’s note: this post originally appeared on the author’s blog, Solve for Interesting. This lightly edited version is reprinted here with permission.

In 10 years, every human connected to the Internet will have a timeline. It will contain everything we’ve done since we started recording, and it will be the primary tool with which we administer our lives. This will fundamentally change how we live, love, work, and play. And we’ll look back at the time before our feed started — before Year Zero — as a huge, unknowable black hole.

This timeline — beginning for newborns at Year Zero — will be so intrinsic to life that it will quickly be taken for granted. Those without a timeline will be at a huge disadvantage. Those with a good one will have the tricks of a modern mentalist: perfect recall, suggestions for how to curry favor, ease maintaining friendships and influencing strangers, unthinkably higher Dunbar numbers — now, every interaction has a history.

This isn’t just about lifelogging health data, like your Fitbit or Jawbone. It isn’t about financial data, like Mint. It isn’t just your social graph or photo feed. It isn’t about commuting data like Waze or Maps. It’s about all of these, together, along with the tools and user interfaces and agents to make sense of it.

Every decade or so, something from military or enterprise technology finds its way, bent and twisted, into the mass market. The client-server computer gave us the PC; wide-area networks gave us the consumer web; pagers and cell phones gave us mobile devices. In the next decade, Year Zero will be how big data reaches everyone. Read more…

Startup Showcase winners reflect the data industry’s maturity

The Strata + Hadoop World 2015 Startup Showcase highlighted four important trends in the big data world.

At Strata + Hadoop World 2015 in San Jose last week, we ran an event for data-driven startups. This is the fourth year for the Startup Showcase, and it’s become a fixture of the conference. One of our early winners, MemSQL, has since raised $50 million in financing, and it’s a good way for companies to get visibility with investors, analysts, and attendees.

This year’s winners underscore several important trends in the big data space at the moment: the maturity of management tools; the deployment of machine learning in other verticals; an increased focus on privacy and permissions; and the convergence of enterprise languages like SQL with distributed, schema-less data stacks. Read more…