Subscribe to the O’Reilly Radar Podcast to track the technologies and people that will shape our world in the years to come.

In this episode of the O’Reilly Radar Podcast, I chat with Dan Shapiro, author and CEO of Glowforge, about his new book Hot Seat: The Startup CEO Guidebook, why startups need co-founders, and why startups are hotbeds for imposter syndrome (and why that’s OK). He also talks a bit about his new endeavor, Glowforge, and how it’s different from other startups he’s launched.

Shapiro explained that the target audience for the book isn’t limited to startup CEOs — in fact, he noted, it’s quite the opposite. “The audience that I’m really excited about getting to see this is everybody who’s not the startup CEO,” he told me. This would include everyone else in the startup ecosystem: co-founders, employees working at a startup, and people employed at big companies who are thinking about taking the leap to found their own startups. He said he wrote this book for “people who are on the cusp or who are touching or who are thinking about that role, either directly or indirectly” — he wrote the book he’d wished he’d had when he started out:

The thing that I wished I’d had in my startup experience — and was always missing — was the honest and unfiltered look at the earliest days of a startup. That was not just, ‘here’s some advice,’ because advice is plentiful and mostly wrong, but real experiences of the stuff that happens. My personal experience, I’m on my fourth or fifth company now, depending on how you count, was that, especially in my first and second companies, I was going through misery and suffering and had these terrible problems. I thought I was the only one who did. I was ashamed to talk about them because everybody else seemed like everything was great and sunny, and I was like, ‘Wow, if my co-founders and I can’t get along, how am I even fit to think about running a company, or shouldn’t we just give up now.’

It was only years later that I realized that almost every set of co-founders has problems and has trouble getting along and runs into issues, and that’s okay. That there are techniques for dealing with that and this is actually really common; it’s just that people are ashamed to talk about it. I wanted to write the book that took lots of peoples’ stories and put them together in the context of, ‘look, startups involve a lot of highs, which there is no shortage of to read about in the press, but a lot of lows as well’ and those are not as often talked about; to talk about some of the experiences of those lows, and strategies for dealing with them.

At one point in the book, Shapiro writes that’s “it’s almost a foregone conclusion that startups need co-founders.” He said there are cases where going solo will work — such as with successful serial entrepreneurs — but for the most part, co-founders are needed for a few of reasons:

I’d say the number one best reason is that at a very fundamental level, the core skill that a CEO has to have is the ability to convince people to join the cause. If the CEO isn’t able to get people to rally behind the company flag, then it is really hard for the company to get anywhere … One of the first questions [an investor has] is, is anybody going to follow the CEO? … When a CEO shows up without co-founders investors will rightfully ask if she’s able to do the job.

…

Very close behind that is that co-founders are typically, if you’re doing it right, top talent, who would be very difficult to afford otherwise, but who are going to be a part because they’re coming in early and because they’ve got a great equity stake and because they’re going to be a foundational part of the team. You really get somebody of a much higher caliber than you might be able to get as an employee if you bring them on as a co-founder.

…

The other reason that I think it makes a big difference is that an investor looks at the company and if they see that there are co-founders, two or three co-founders who’ve already reached arrangements and split the company between them, and then let’s say that investor buys 20% of the company, they’re getting three great high-caliber co-founders. Whereas if there is just one, and the investor buys 20% of the company, they are only getting one. Research says that founders typically get paid less in cash than regular employees, and oftentimes they’re better qualified than or more senior than the employees that an early stage company might have. The investor basically just gets more for their dime.

One of the topics in the book that Shapiro covers in-depth is imposter syndrome — that feeling that you don’t really belong where you are, that you’re not qualified, and that someone will eventually find you out. Shapiro said startups are a hot bed for this phenomenon, but that it’s not such a bad thing when approached with the right perspective:

Some people feel that weight more heavily than others, but I think the first thing is just knowing that it’s okay is a huge piece of it. Knowing that nobody really knows what they’re getting into the first time they’re taking a job like that. … Some people feeling like they’re faking it give up or try to avoid situations where they might be outed or otherwise wind up sabotaging themselves because of this lack of confidence. Other people use it to spur themselves to ever-greater heights because they feel like everybody else knows what they’re doing and they don’t. They feel that they have to work all the harder in order to keep up.

As you can imagine, if everybody is faking it and everybody is lost, then the person who takes that to heart and works to get themselves unlost as quickly and as clearly as possible is at a tremendous advantage to the people who are quietly faking it and trying not to get caught. Imposter phenomenon can actually be incredibly motivating, and everybody is going to understand where they sit on that range from complete confidence in their abilities to total desperation. … In many cases, just knowing and understanding what’s going on can be a huge psychological relief, knowing that you’re not alone and that this is really common and happens to a lot of people.

You can listen to the podcast in the player embedded above or download it through Stitcher, TuneIn, SoundCloud, or iTunes.

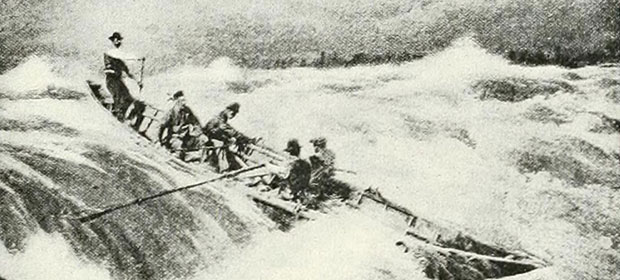

Public domain image via the Internet Archive on Flickr.