Alistair Croll

Design matters more than math

Design compels. Math is proof. Both sides will defend their domains at Strata's next Great Debate.

At Strata Santa Clara later this month, we’re reprising what has become a tradition: Great Debates. These Oxford-style debates pit two teams against one another to argue a hot topic in the fields of big data, ubiquitous computing, and emerging interfaces.

Part of the fun is the scoring: attendees vote on whether they agree with the proposal before the debaters; and after both sides have said their piece, the audience votes again. Whoever moves the needle wins.

Part of the fun is the scoring: attendees vote on whether they agree with the proposal before the debaters; and after both sides have said their piece, the audience votes again. Whoever moves the needle wins.

This year’s proposition — that design matters more than math — is sure to inspire some vigorous discussion. The argument for math is pretty strong. Math is proof. Given enough data — and today, we have plenty — we can know. “The right information in the right place just changes your life,” said Stewart Brand. Properly harnessed, the power of data analysis and modeling can fix cities, predict epidemics, and revitalize education. Abused, it can invade our lives, undermine economies, and steal elections. Surely the algorithms of big data matter!

But your life won’t change by itself. Bruce Mau defines design as “the human capacity to plan and produce desired outcomes.” Math informs; design compels. Without design, math can’t do its thing. Poorly designed experiments collect the wrong data. And if the data can’t be understood and acted upon, it may as well not have been crunched in the first place.

This is the question we’ll be putting to our debaters: Which matters more? A well-designed collection of flawed information — or an opaque, hard-to-parse, but unerringly accurate model? From mobile handsets to social policy, we need both good math and good design. Which is more critical? Read more…

The business singularity

How the inevitable rise of software means cycle time trumps scale.

Exponential curves gradually, inexorably grow until they reach a limit. The function increases over time. That’s why a force like gravity, which grows exponentially as objects with mass get closer to one another, eventually leads to a black hole. And at the middle of this black hole is a point of infinite mass, a singularity, within which the rules no longer apply.

Financiers also like exponents. “Compound interest is the most powerful force in the universe” is a quote often attributed to Einstein; whoever said it was right. If you pump the proceeds of interest back into a bank account, it’ll increase steadily.

Computer scientists like to throw the term “singularity” around, too. To them, it’s the moment when machines become intelligent enough to make a better machine. It’s the Geek Rapture, the capital-S-Singularity. It’s the day when machines don’t need us any more, and to them, we look like little more than ants. Ray Kurzweil thinks it’s right around the corner — circa 2045 — and after that time, to us, these artificial intelligences will be incomprehensible.

Businesses need to understand singularities, because they have one of their own to contend with. Read more…

Stacks get hacked: The inevitable rise of data warfare

The cycle of good, bad, and stable has happened at every layer of the stack. It will happen with big data, too.

First, technology is good. Then it gets bad. Then it gets stable.

This has been going on for a long time, likely since the invention of fire, knives, or the printed word. But I want to focus specifically on computing technology. The human race is busy colonizing a second online world and sticking prosthetic brains — today, we call them smartphones — in front of our eyes and ears. And stacks of technology on which they rely are vulnerable.

When we first created automatic phone switches, hackers quickly learned how to blow a Cap’n Crunch whistle to get free calls from pay phones. When consumers got modems, attackers soon figured out how to rapidly redial to get more than their fair share of time on a BBS, or to program scripts that could brute-force their way into others’ accounts. Eventually, we got better passwords and we fixed the pay phones and switches.

We moved up the networking stack, above the physical and link layers. We tasted TCP/IP, and found it good. Millions of us installed Trumpet Winsock on consumer machines. We were idealists rushing onto the wild open web and proclaiming it a new utopia. Then, because of the way the TCP handshake worked, hackers figured out how to DDOS people with things like SYN attacks. Escalation, and router hardening, ensued.

We built HTTP, and SQL, and more. At first, they were open, innocent, and helped us make huge advances in programming. Then attackers found ways to exploit their weaknesses with cross-site scripting and buffer overruns. They hacked armies of machines to do their bidding, flooding target networks and taking sites offline. Technologies like MP3s gave us an explosion in music, new business models, and abundant crowd-sourced audiobooks — even as they leveled a music industry with fresh forms of piracy for which we hadn’t even invented laws. Read more…

Thin walls and traffic cameras

We need checks and balances to ensure data-driven predictions don't become prejudices.

A couple of years ago, I spoke with a European Union diplomat who shall remain nameless about the governing body’s attitude toward privacy.

A couple of years ago, I spoke with a European Union diplomat who shall remain nameless about the governing body’s attitude toward privacy.

“Do you know why the French hate traffic cameras?” he asked me. “It’s because it makes it hard for them to cheat on their spouses.”

He contended that while it was possible for a couple to overlook subtle signs of infidelity — a brush of lipstick on a collar, a stray hair, or the smell of a man’s cologne — the hard proof of a speeding ticket given on the way to an afternoon tryst couldn’t be ignored.

Humans live in these grey areas. A 65 mph speed limit is really a suggestion; it’s up to the officers to enforce that limit. That allows for context: a reckless teen might get pulled over for going 70, but a careful driver can go 75 without incident.

But a computer that’s programmed to issue tickets to speeders doesn’t have that ambiguity. And its accusations are hard to ignore because they’re factual, rooted in hard data and numbers.

Did big data kill privacy?

With the rise of a data-driven society, it’s tempting to pronounce privacy dead. Each time we connect to a new service or network, we’re agreeing to leave a digital breadcrumb trail behind us. And increasingly, not connecting makes us social pariahs, leaving others to wonder what we have to hide.

But maybe privacy is a fiction. For millennia — before the rise of city-states — we lived in villages. Gossip, hearsay, and whisperings heard through thin-walled huts were the norm.

Shared moral values and social pressure helped groups to compete better against other groups, helping to evolve the societies and religions that dominate the world today. Humans thrive in part because of our groupish nature — which is why moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt says we’re 90% chimp and 10% bee. We might have evolved as selfish individuals, but we conquered the Earth as selfish teams.

In other words, being private is relatively new, perhaps only transient, and gossip helped us get here. Read more…

Startup Showcase: And the finalists are …

A compelling crop of companies will present at the Strata Conference + Hadoop World Startup Showcase.

We had a wide range of startups apply for a slot in the Strata Conference + Hadoop World Startup Showcase. Our selection committee, which included investors, entrepreneurs, and executives from SAP — which is sponsoring the event — whittled these down to just a few, who will get a chance to strut their stuff in the Big Apple next week.

All sorts of early-stage firms applied, both those using data as a key differentiator, and those building the next-generation infrastructures that can handle the torrent of information our world produces. We also had applicants who visualize, communicate, and democratize, turning complex, chewy data into bite-sized, interactive nuggets that are easier to digest.

It’s a compelling crop of new entrants into today’s vibrant big data ecosystem, and we’re thrilled to welcome them to next week’s event, where Tim O’Reilly and Fred Wilson face the unenviable task of choosing the top three.

Startup Showcase finalists

New ethics for a new world

The biggest threat that a data-driven world presents is an ethical one.

Since the first of our ancestors chipped stone into weapon, technology has divided us. Seldom more than today, however: a connected, always-on society promises health, wisdom, and efficiency even as it threatens an end to privacy and the rise of prejudice masked as science.

On its surface, a data-driven society is more transparent, and makes better uses of its resources. By connecting human knowledge, and mining it for insights, we can pinpoint problems before they become disasters, warding off disease and shining the harsh light of data on injustice and corruption. Data is making cities smarter, watering the grass roots, and improving the way we teach.

But for every accolade, there’s a cautionary tale. It’s easy to forget that data is merely a tool, and in the wrong hands, that tool can do powerful wrong. Data erodes our privacy. It predicts us, often with unerring accuracy — and treating those predictions as fact is a new, insidious form of prejudice. And it can collect the chaff of our digital lives, harvesting a picture of us we may not want others to know.

The big data movement isn’t just about knowing more things. It’s about a fundamental shift from scarcity to abundance. Most markets are defined by scarcity — the price of diamonds, or oil, or music. But when things become so cheap they’re nearly free, a funny thing happens.

Consider the advent of steam power. Economist Stanley Jevons, in what’s known as Jevons’ Paradox, observed that as the efficiency of steam engines increased, coal consumption went up. That’s not what was supposed to happen. Jevons realized that abundance creates new ways of using something. As steam became cheap, we found new ways of using it, which created demand.

The same thing is happening with data. A report that took a month to run is now just a few taps on a tablet. An unthinkably complex analysis of competitors is now a Google search. And the global distribution of multimedia content that once required a broadcast license is now an upload. Read more…

Follow up on big data and civil rights

Further reading and discussion on the civil rights implications of big data.

A few weeks ago, I wrote a post about big data and civil rights, which seems to have hit a nerve. It was posted on Solve for Interesting and here on Radar, and then folks like Boing Boing picked it up.

I haven’t had this kind of response to a post before (well, I’ve had responses, such as the comments to this piece for GigaOm five years ago, but they haven’t been nearly as thoughtful).

Some of the best posts have really added to the conversation. Here’s a list of those I suggest for further reading and discussion:

Nobody notices offers they don’t get

On Oxford’s Practical Ethics blog, Anders Sandberg argues that transparency and reciprocal knowledge about how data is being used will be essential. Anders captured the core of my concerns in a single paragraph, saying what I wanted to far better than I could:

… nobody notices offers they do not get. And if these absent opportunities start following certain social patterns (for example not offering them to certain races, genders or sexual preferences) they can have a deep civil rights effect

To me, this is a key issue, and it responds eloquently to some of the comments on the original post. Harry Chamberlain commented:

However, what would you say to the criticism that you are seeing lions in the darkness? In other words, the risk of abuse certainly exists, but until we see a clear case of big data enabling and fueling discrimination, how do we know there is a real threat worth fighting?

Three kinds of big data

Looking ahead at big data's role in enterprise business intelligence, civil engineering, and customer relationship optimization.

In the past couple of years, marketers and pundits have spent a lot of time labeling everything “big data.” The reasoning goes something like this:

In the past couple of years, marketers and pundits have spent a lot of time labeling everything “big data.” The reasoning goes something like this:

- Everything is on the Internet.

- The Internet has a lot of data.

- Therefore, everything is big data.

When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When you have a Hadoop deployment, everything looks like big data. And if you’re trying to cloak your company in the mantle of a burgeoning industry, big data will do just fine. But seeing big data everywhere is a sure way to hasten the inevitable fall from the peak of high expectations to the trough of disillusionment.

We saw this with cloud computing. From early idealists saying everything would live in a magical, limitless, free data center to today’s pragmatism about virtualization and infrastructure, we soon took off our rose-colored glasses and put on welding goggles so we could actually build stuff.

So where will big data go to grow up?

Once we get over ourselves and start rolling up our sleeves, I think big data will fall into three major buckets: Enterprise BI, Civil Engineering, and Customer Relationship Optimization. This is where we’ll see most IT spending, most government oversight, and most early adoption in the next few years. Read more…

Big data is our generation’s civil rights issue, and we don’t know it

What the data is must be linked to how it can be used.

Data doesn’t invade people’s lives. Lack of control over how it’s used does.

What’s really driving so-called big data isn’t the volume of information. It turns out big data doesn’t have to be all that big. Rather, it’s about a reconsideration of the fundamental economics of analyzing data.

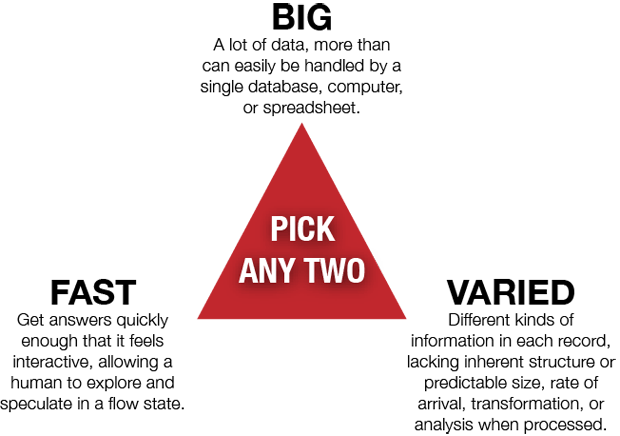

For decades, there’s been a fundamental tension between three attributes of databases. You can have the data fast; you can have it big; or you can have it varied. The catch is, you can’t have all three at once.

I’d first heard this as the “three V’s of data”: Volume, Variety, and Velocity. Traditionally, getting two was easy but getting three was very, very, very expensive.

The advent of clouds, platforms like Hadoop, and the inexorable march of Moore’s Law means that now, analyzing data is trivially inexpensive. And when things become so cheap that they’re practically free, big changes happen — just look at the advent of steam power, or the copying of digital music, or the rise of home printing. Abundance replaces scarcity, and we invent new business models.

In the old, data-is-scarce model, companies had to decide what to collect first, and then collect it. A traditional enterprise data warehouse might have tracked sales of widgets by color, region, and size. This act of deciding what to store and how to store it is called designing the schema, and in many ways, it’s the moment where someone decides what the data is about. It’s the instant of context.

That needs repeating:

You decide what data is about the moment you define its schema.

Survey results: How businesses are adopting and dealing with data

A glimpse into enterprise use of big data.

Feedback from a recent Strata Online Conference suggests there's a large demand for clear information on what big data is and how it will change business.