Just when it seems we’re starting to get our heads around the mobile revolution, another design challenge has risen up fiercer and larger right behind it: the Internet of Things. The rise in popularity of “wearables” and the growing activity around NFC and Bluetooth LE technologies are pushing the Internet of Things increasingly closer to the mainstream consumer market. Just as some challenges of mobile computing were pointedly addressed by responsive web design and adaptive content, we must carefully evaluate our approach to integration, implementation, and interface in this emerging context if we hope to see it become an enriching part people’s daily lives (and not just another source of anger and frustration).

It is with this goal in mind that I would like to offer a series of posts as one starting point for a conversation about user interface design, user experience design, and information architecture for connected environments. I’ll begin by discussing the functional relationship between user interface design and information architecture, and by drawing out some implications of this relationship for user experience as a whole.

In follow-up posts, I’ll discuss the library sciences origins of information architecture as it has been traditionally practiced on the web, and situate this practice in the emerging climate of connected environments. Finally, I’ll wrap up the series by discussing the cognitive challenges that connected systems present and propose some specific measures we can take as designers to make these systems more pleasant, more intuitive, and more enriching to use.

Architecture and Design

Technology pioneer Kevin Ashton is widely credited with coining the term “The Internet of Things.” Ashton characterizes the core of the Internet of Things as the “RFID and sensor technology [that] enables computers to observe, identify, and understand the world — without the limitations of human-entered data.”

About the same time that Ashton gave a name to this emerging confluence of technologies, scholar N. Katherine Hayles noted in How We Became Posthuman that “in the future, the scarce commodity will be the human attention span.” In effect, collecting data is a technology problem that can be solved with efficiency and scale; making that mass of data meaningful to human beings (who evolve on a much different timeline) is an entirely different task.

The twist in this story? Both Ashton and Hayles were formulating these ideas circa 1999. Now, 14 years later, the future they identified is at hand. Bandwidth, processor speed, and memory will soon be up to the task of ensuring the technical end of what has already been imagined, and much more. The challenge before us now as designers is in making sure that this future-turned-present world is not only technically possible, but also practically feasible — in a word, we still need to solve the usability problem.

Fortunately, members of the forward guard in emerging technology have already sprung into action and have begun to outline the specific challenges presented by the connected environment. Designer and strategist Scott Jenson has written and spoken at length about the need for open APIs, flexible cloud solutions, and the need for careful attention to the “pain/value” ratio. Designer and researcher Stephanie Rieger likewise has recently drawn our collective attention to advances in NFC, Android intent sharing, and behavior chaining that all work to tie disparate pieces of technology together.

These challenges, however, lie primarily on the “computer” side of the Human Computer Interaction (HCI) spectrum. As such, they give us only limited insight into how to best accommodate Hayles’ “scarce commodity” – the human attention span. By shifting our point of view from how machines interact with and create information to the way that humans interact with and consume information, we will be better equipped to make the connections necessary to create value for individuals. Understanding the relationship between architecture and design is an important first step in making this shift.

Information Architect Dan Klyn explains the difference between architecture and design with a metaphor of tailoring: the architect determines where the cuts should go in the fabric, the designer then brings those pieces together to make the finished product the best it can be, “solving the problems defined in the act of cutting.”

Along the way, the designer may find that some cuts have been misplaced – and should be stitched back together or cut differently from a new piece. Likewise, the architect remains active and engaged in the design phase, making sure each piece fits together in a way that supports the intent of the whole.

The end result – be it a well-fitted pair of skinny jeans or a user interface – is a combination of each of these efforts. As Klyn puts it, the architect specializes in determining what must be built and in determining the overall structure of the finished product; the designer focuses on how to put that product together in a way that is compelling and effective within the constraints of a given context.

Once we make this distinction clear, it becomes equally clear that user interface design is a context-specific articulation of an underlying information architecture. It is this IA foundation that provides the direct connection to how human end users find value in content and functionality. The articulatory relationship between architecture and design creates consistency of experience across diverse platforms and works to communicate the underlying information model we’ve asked users to adopt.

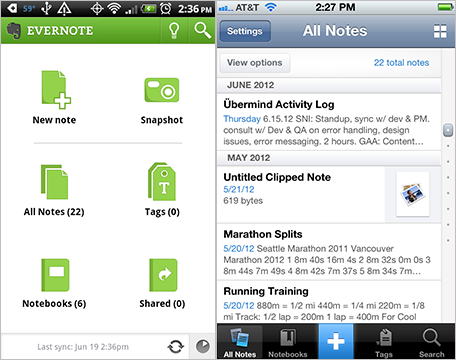

Let’s look at an example. The early Evernote app had a very different look and feel on iOS and Android. On Android, it was a distinctly “Evernote-branded” experience. On iOS, on the other hand, it was designed to look more like a piece of the device operating system.

Despite the fact that these apps are aesthetically different, their architectures are consistent across platforms. As a result, even though the controls are presented in different ways, in different places, and at different levels of granularity, moving between the apps is a cognitively seamless experience for users.

In fact, apps that “look” the same across different platforms sometimes end up creating architectural inconsistencies that may ultimately confuse users. This is most easily seen in the case of “ported applications,” where iPhone user interfaces are “ported over” whole cloth to Android devices. The result is usually a jumble of misplaced back buttons and errant tab bars that send mixed messages about the effects of native controls and patterns. This, in turn, sends a mixed message about the information model we have proposed. The link between concept-rooted architecture and context-rooted design has been lost.

In the case of such ports, the full implication of the articulatory relationship between information architecture and user interface becomes clear. In these examples, we can see that information architecture always happens: either it happens by design or it happens by default. As designers, we sometimes fool ourselves into thinking that a particular app or website “doesn’t need IA,” but the reality is that information architecture is always present — it’s just that we might have specified it in a page layout instead of a taxonomy tool (and we might not have been paying attention when that happened).

Once we step back from the now familiar user interface design patterns of the last few years and examine the information architecture structures that inform them, we can begin to develop a greater awareness (and control) of how those structures are articulated across devices and contexts. We can also begin to cultivate the conditions necessary for that articulation to happen in terms that make sense to users in the context of new devices and systems, which subsequently increases our ability to capitalize on those devices’ and systems’ unique capabilities.

This basic distinction between architecture and design is not a new idea, but in the context of the Internet of Things, it does present architects and designers with a new set of challenges. In order to get a better sense of what has changed in this new context, it’s worth taking a closer look at how the traditional model of IA for the web works. This is the topic to which I’ll turn in my next post.